Water Stress, Wastewater, and a New Economic Sector

India’s environmental organisation and environmental NGO ecosystem is entering a new phase where water recycling is no longer just a sustainability issue but a core economic opportunity.

India is home to 18 percent of the global population but has access to only 4 percent of the world’s water resources, making it one of the most water-stressed countries in the world. This imbalance is now pushing policymakers, industries, and ESG investors to see wastewater as a strategic resource rather than a liability.

According to the Composite Water Management Index of NITI Aayog, nearly 600 million Indians face high to extreme water stress and several major cities are projected to run out of groundwater in the coming years.You can see this framework in NITI Aayog’s report on water management and stress indicators.

At the same time, urban India generates more than 72,000 million litres per day of sewage, while treatment capacity and utilisation lag significantly behind this volume. An analysis of the urban wastewater scenario in India, based on Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) data, shows that treatment capacity is much lower than sewage generated and a significant share of installed plants does not function at full capacity.

Untreated sewage is one of the primary reasons for river pollution, groundwater contamination, and public health risks in India’s cities.For an environmental organisation like Earth5R, which works at the intersection of sustainability, waste management, river cleaning, CSR and ESG, this untreated wastewater represents both a threat and a billion-dollar opportunity for environmental social governance driven investment.

India’s Wastewater Reality: Data, Deficits, and Policy Pressure

India’s water crisis is not only about scarcity of freshwater but also about mismanagement of wastewater.The World Bank notes that India has 18 percent of the world’s population but only 4 percent of global water resources, which places it in the category of water-stressed countries.

At the same time, rapid urbanisation and industrialisation are increasing demand for water in municipal and industrial sectors. An overview of India’s urban wastewater management shows that around 72,368 MLD of sewage is generated in urban areas, while installed treatment capacity is about 31,841 MLD and the effective operational capacity is even lower.

This means that more than half of the sewage generated does not receive adequate treatment and much of it flows directly into rivers, lakes, and coastal waters.The result is a major environmental and public health challenge that also undermines India’s economic productivity.

NITI Aayog’s work on water management and several independent analyses highlight how untreated wastewater contributes to deteriorating river quality, increased waterborne diseases, and reduced availability of safe water for households and industries.

These findings reinforce the urgency for cities to move from a linear water model to a circular water economy.The policy environment is gradually responding through missions and schemes that prioritise sewage treatment and reuse.National programmes such as the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), the Smart Cities Mission, and the National Mission for Clean Ganga (Namami Gange) include sewage treatment plants and interceptor sewers as critical components.

Many state governments are now issuing policies that encourage or mandate the use of treated sewage effluent for industrial and non-potable applications.However, the pace of implementation and the scale of recycling still fall short of what is needed to secure India’s water future.

Why Water Recycling Is Economically More Attractive Than Freshwater Extraction

From a pure economic perspective, using only freshwater is becoming increasingly costly for Indian cities and industries.The World Bank’s feature on India’s water needs emphasises that per capita water availability is already below the threshold for water stress and is moving closer to conditions of water scarcity.

Extracting, transporting, and treating freshwater from distant reservoirs, rivers, or groundwater aquifers requires high capital and operating expenditure.In contrast, wastewater is already present within cities and industrial zones.When treated to appropriate quality, it can be supplied at a stable price and used for cooling, process water, landscaping, and even agriculture.

Studies and case examples from cities such as Nagpur show that treated wastewater can often be supplied to industrial users at a cost that is 20 to 40 percent lower than the full economic cost of freshwater.

The World Bank report on “Wastewater: From Waste to Resource – The Case of Nagpur, India” documents how a large tertiary treatment plant was developed through a long-term contract to supply treated sewage to power plants.In this model, the city turned wastewater into a revenue-generating resource while reducing pressure on freshwater sources.

This kind of arrangement demonstrates the financial logic of treating sewage as an input to a new water market.For India’s ESG investors and corporate social responsibility programs, such projects offer a clear business case.Instead of viewing sewage plants only as compliance infrastructure, they can be seen as assets that generate stable cash flows by selling recycled water to industrial customers.

Environmental social governance metrics then become directly tied to revenue and cost savings, not just to regulatory reporting.

Who Will Own the Billion-Dollar Water Recycling Market in India?

As India’s water recycling sector grows into a billion-dollar space, the central question is ownership.Will municipalities own and operate most of the infrastructure, or will private concessionaires, industrial consortia, and PPP models dominate the market.The answer is likely to be a mix, but the current trajectory offers clues.

NITI Aayog’s Compendium of Best Practices in Water Management documents multiple models where state utilities, city governments, and private partners collaborate on sewage treatment and reuse.These include PPP contracts, design–build–operate concessions, and long term purchase agreements for treated water.At the same time, industrial associations in water-stressed states are increasingly willing to commit to off-take guarantees for recycled water.

The ownership question also extends to data, monitoring, and ESG reporting.Who will own and manage the information systems that track water quality, recycled volumes, and environmental impact.As ESG reporting standards become stricter, industries are likely to demand transparent and verifiable data from the entities that supply them with recycled water.

Environmental NGOs and environmental organisations like Earth5R play a bridging role in this emerging market.They connect communities, local governments, and industries and help ensure that water recycling investments do not ignore social equity and river health.

In practice, this means aligning financial models with community outcomes and transparent environmental indicators.

Earth5R’s On-Ground Learning: Rivers, Waste Management, and Circular Water

Earth5R’s experience as an environmental organisation from India offers practical lessons for the water recycling discussion.Through its work in river cleaning, waste management, community education, and CSR projects, Earth5R has seen how untreated wastewater disrupts local ecosystems and livelihoods.It has also seen how circular models can unlock new forms of value.

The Mithi River community cleanup model demonstrates how plastic pollution, solid waste, and sewage combine to create chronic urban flood risks and health hazards in Mumbai.Earth5R’s model emphasises waste segregation, citizen participation, and partnerships with local authorities to address both solid waste and upstream sewage sources.

The river is treated as part of a broader urban sustainability system rather than a standalone cleanup site.Earth5R’s work on river, lake, and beach cleanup projects across India shows that river cleaning cannot be separated from waste management and water infrastructure.

When sewage lines leak or are absent, and when informal settlements are not connected to proper sanitation, river restoration efforts face constant reversal.For this reason, Earth5R increasingly frames its river cleaning work as a platform for circular economy projects, including potential water recycling and reuse.

In parallel, Earth5R’s waste management and circular economy programs in communities and slums demonstrate how decentralised systems can reduce the flow of waste and pollution into river systems.These programs use environmental education, livelihood creation, and citizen science to change behaviour and build local stewardship.

The same approach can be extended to community participation in monitoring local drains, sewage outfalls, and the performance of treatment systems.

Policy and Regulatory Drivers: From Sewage Control to Water Markets

The regulatory environment around wastewater in India is tightening.Under the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, industries and local bodies are required to treat wastewater to specified standards before discharge.The Central Pollution Control Board issues guidelines and monitors compliance, and state pollution control boards enforce standards at the regional level.More recent initiatives build on this foundation.

The Urban Wastewater Scenario in India analysis, supported by national agencies, points out that untreated sewage is the largest single source of surface water pollution.This has led to greater emphasis on sewage networks, sewage treatment plants, and reuse guidelines in national schemes.

Some state-level policies now require industries located near treatment plants to use treated sewage effluent instead of freshwater for certain applications.Urban local bodies are encouraged to sign long-term contracts for the sale of treated wastewater to thermal power plants, industrial clusters, and large commercial consumers.

Such steps are slowly shaping wastewater into a tradable urban resource.For CSR and ESG programs, this regulatory evolution opens new project opportunities. Businesses can fund upgrades to treatment plants, build decentralised sewage treatment in underserved communities, or support monitoring and data platforms.When these projects are framed as part of a water recycling market, they move from one-off CSR spending to long-term ESG value creation.

Industrial Clusters and Special Economic Zones as Early Movers

Industrial estates, special economic zones, and industrial corridors are emerging as early adopters of recycled water.Many of these zones are located in regions where freshwater is scarce or groundwater is already over-exploited.They are therefore under strong pressure to adopt alternative water sources.

Case studies from water-stressed cities show industries entering long-term agreements to use tertiary-treated wastewater for cooling and process needs.The Nagpur wastewater reuse project has been highlighted internationally as a proof of concept where sewage treatment and reuse can be financially viable through a combination of PPP design and power-plant off-take.

This model is now referenced in technical and policy discussions on urban water reuse in India.In the coming decade, industrial users are likely to become the anchor customers for most large water recycling projects in India.

They have predictable demand, stronger capacity to pay, and direct incentives to demonstrate environmental social governance performance.The challenge is to ensure that industrial reuse is linked to broader river cleaning and community benefits rather than operating as an isolated industrial utility.

Social Equity, River Health, and The Role of Environmental NGOs

The expansion of a billion-dollar water recycling sector raises important questions about equity and river health.If recycled water is sold only to industries, will nearby communities still suffer from polluted streams and drains.Will marginalised settlements continue to live next to open sewers even as high-tech recycling plants serve industrial parks.

Earth5R’s work on cleaning India’s rivers through behaviour change, technology, and partnerships underlines that infrastructure alone is not enough.Communities need to understand the value of river cleaning and hold institutions accountable for how sewage and wastewater are managed.This includes citizens demanding that local drains be connected to functioning treatment systems and that riverbanks be protected as common ecological assets.

Environmental NGOs and environmental organisations can help design projects where CSR budgets finance both physical infrastructure and social components such as environmental education, livelihood creation, and citizen science.

Earth5R’s CSR and ESG projects show how river cleanup, waste management, and community engagement can be integrated into a single long-term program.In a water recycling economy, similar integrated approaches will be necessary to avoid purely technocratic solutions that leave social gaps unaddressed.

Actionable Pathways: How India Can Build a Fair and Profitable Water Recycling Sector

For India to fully unlock water recycling as a billion-dollar sector, several actionable steps stand out.These steps involve governments, industries, financial institutions, and environmental NGOs working in a coordinated manner.They also reflect Earth5R’s field experience across Indian cities and rivers.

First, cities need clear reuse targets linked to their sewage treatment plants.Instead of measuring only installed capacity, they should track how much treated wastewater is actually reused for industrial, agricultural, or landscaping purposes.Public dashboards and open data can increase transparency and attract ESG funds into high-performing cities.

Second, PPP contracts must be designed with long term stability, transparent tariffs, and strong environmental safeguards.Municipalities can tender projects where private operators design, build, and operate tertiary treatment plants and guarantee supply of recycled water to industrial offtakers.Regulators and civil society should be able to verify both the quantity and quality of recycled water.

Third, CSR and ESG frameworks should treat water recycling as a strategic investment area.

Companies can support decentralised treatment plants in informal settlements, sponsor monitoring technology for rivers, or co-invest in city-scale reuse infrastructure that benefits both industries and communities.Such projects can be anchored in partnerships with environmental NGOs like Earth5R that bring community trust and implementation capacity.

Fourth, community engagement must be built into every water recycling project.Earth5R’s river cleanup ecosystem approach shows that involving citizens, students, and local leaders leads to more resilient outcomes.When communities understand how sewage, waste management, and river health are connected, they are more likely to support and protect new infrastructure.

FAQs: India’s Next Billion-Dollar Sector Is Water Recycling, But Who Will Own It?: Earth5R Economic Outlook

What is driving the growth of the water recycling sector in India?

Severe water stress, rapid urbanisation, industrial demand, and rising ESG expectations are pushing wastewater to be viewed as a valuable economic resource.

Why is India considered one of the most water-stressed countries in the world?

India has 18% of the global population but only 4% of global freshwater resources, creating a major supply–demand imbalance.

How much sewage does urban India generate every day?

Urban India generates over 72,000 million litres per day of sewage, much of which remains untreated.

Why is untreated wastewater a major environmental threat?

Untreated sewage pollutes rivers, contaminates groundwater, spreads disease, and damages urban ecosystems.

How does water recycling create economic value?

Treated wastewater can be sold to industries at lower costs than freshwater, turning sewage treatment plants into revenue-generating assets.

Why is recycled water cheaper than freshwater for industries?

It avoids costs linked to long-distance extraction, transport, and over-exploitation of groundwater and surface water sources.

What role do industrial users play in the water recycling market?

Industries act as anchor customers with stable demand and the financial capacity to support long-term recycled water contracts.

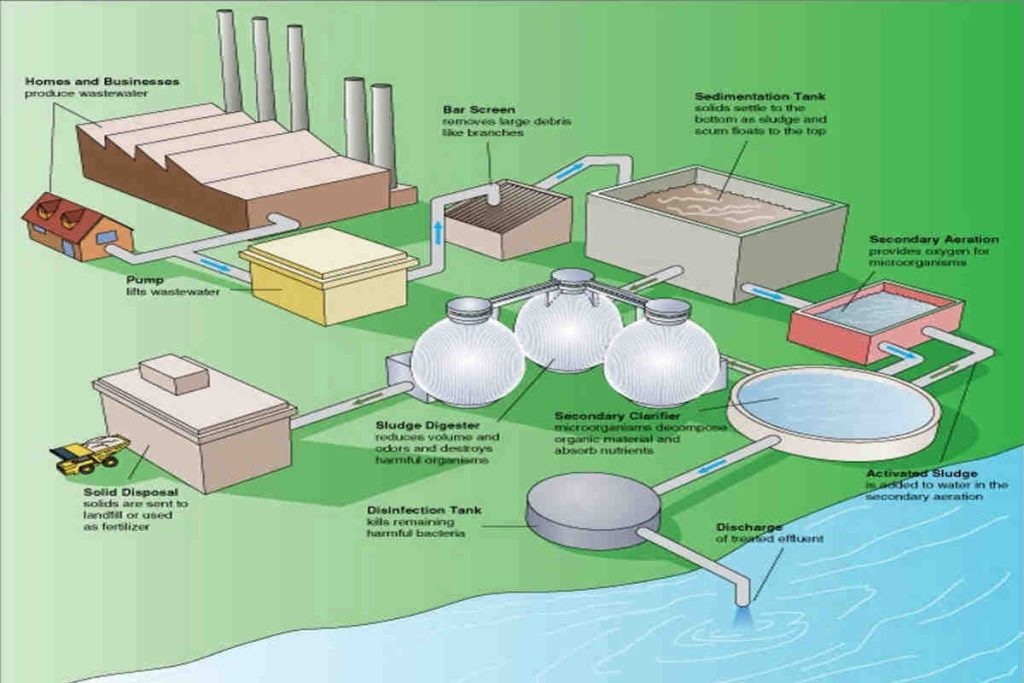

What is the circular water economy model?

It involves treating wastewater as a reusable resource rather than a waste product, creating continuous cycles of reuse.

How are government policies supporting wastewater reuse?

National missions and state-level policies are promoting sewage treatment, reuse mandates, and long-term supply contracts.

What ownership models are emerging in India’s water recycling sector?

Public ownership, private concessions, PPP models, and industrial off-take agreements are all taking shape.

Why is transparency in water data becoming important?

Stronger ESG reporting standards require verified data on water quality, reuse volumes, and environmental impact.

What risks exist if water recycling benefits only industries?

Marginalised communities may continue to live near polluted drains while recycled water supports only industrial users.

How does water recycling support river health?

By reducing the discharge of untreated sewage into rivers, recycling directly improves water quality and ecosystem recovery.

Why is community participation crucial in water recycling projects?

Citizen involvement improves monitoring, accountability, infrastructure protection, and long-term sustainability.

How do CSR and ESG programs connect with water recycling?

They fund treatment upgrades, decentralised plants, river monitoring systems, and community education programs.

What lessons come from India’s river cleanup experiences?

River cleaning fails if sewage, solid waste, sanitation access, and community behaviour are not addressed together.

How can decentralised treatment help underserved areas?

It reduces pollution at the source, improves sanitation, and prevents waste from reaching major river systems.

What makes water recycling attractive to ESG investors?

It offers measurable environmental impact, stable revenue streams, resource security, and regulatory alignment.

What policy shift is turning wastewater into a tradable resource?

Mandatory treatment standards, reuse guidelines, and industrial reuse obligations are transforming sewage into a market commodity.

Who should ultimately “own” India’s water recycling future?

A shared ownership model involving municipalities, industries, investors, environmental organisations, and local communities is essential for long-term success.

Owning the Future of Circular Water in India

India’s next billion-dollar sustainability sector is clearly emerging around water recycling and circular water systems.The combination of water stress, urbanisation, industrial demand, and rising ESG expectations is reshaping how wastewater is perceived and valued.

What was once seen as an unavoidable by-product of urban life is now central to economic planning, corporate social responsibility, and environmental social governance metrics.The key question is not whether water recycling will grow, but who will own and shape this sector in India.

If municipalities, industries, investors, and environmental NGOs collaborate with communities at the centre, the result can be a fair and resilient circular water economy.

If they do not, water recycling risks becoming a narrow industrial service that leaves rivers polluted and vulnerable communities behind.

As an environmental organisation rooted in India, Earth5R is already working at this intersection of river cleaning, waste management, CSR, ESG, and community engagement.

Its projects and insights show that the ownership of India’s water recycling future must be shared between institutions and citizens.

Only then will India’s next billion-dollar sector deliver not just profits but real sustainability, healthier rivers, and a secure water future for its people.

Authored by- Sneha Reji