Cities across the world are entering a new era of water stress. Rapid urbanisation, erratic rainfall patterns, and rising temperatures have pushed many metropolitan regions to the edge. The signs are often visible in everyday life. Taps run dry more frequently. Tanker trucks appear on crowded streets long before summer begins. Local lakes shrink or turn toxic. These incidents are no longer isolated episodes. They are signals of a deeper systems challenge that traditional water infrastructure can no longer solve alone.

Most Indian cities operate with centralised water networks designed decades ago. These systems rely on distant sources, long pipelines, and expensive treatment plants. As populations expand, these networks struggle to keep pace. They become vulnerable to leaks, climate shocks, and supply disruptions. At the same time, city budgets find it harder to finance ever-larger centralised projects. This gap between demand and capacity has created an urgent need to rethink how cities manage water.

A decentralised water management system offers a promising alternative. Instead of depending solely on large central plants, it distributes treatment, reuse, and storage across neighbourhoods, institutions, and industrial zones. Such systems treat water closer to where it is used. They reduce losses, support recycling, and make cities more resilient during crises. Countries across Asia, Europe, and Africa are increasingly turning toward localised water solutions to strengthen their urban resilience.

The need for decentralisation becomes clearer when we examine the warning signals visible in many cities today. Persistent groundwater depletion, repeated flooding, ageing pipelines, and rising costs indicate that current approaches are no longer sustainable. Each of these signs reflects the pressure on our centralised systems. Together, they form a pattern that cannot be ignored.

This review identifies 11 key signs that show when a city must adopt decentralised water management. The analysis draws on verified studies, policy documents, sustainability research, and urban case examples from India and abroad. The goal is not only to diagnose the problem but to provide readers with a grounded understanding of why decentralised systems are essential for the future of urban water security.

If your city shows several of these warning signs, it may already be time to act.

What is a Decentralised Water Management System?

Cities have long depended on large centralised water systems. These networks collect water from distant sources, treat it in big plants, and transport it across vast pipelines. While this model worked when cities were smaller, it is now under strain. A decentralised water management system offers a different approach that distributes the responsibility for treatment, reuse, and storage across multiple smaller units located closer to the point of use.

Definition and Scope

A decentralised water management system is a locally based method of handling water supply, wastewater, stormwater, or recycled water. Instead of relying on a single central plant, it uses smaller facilities placed within communities, institutions, industrial clusters, or neighbourhoods. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, decentralised systems range from on-site wastewater treatment units to cluster systems serving entire communities. These systems aim to handle water where it is generated, reducing the need for long-distance transport or centralised dependency.

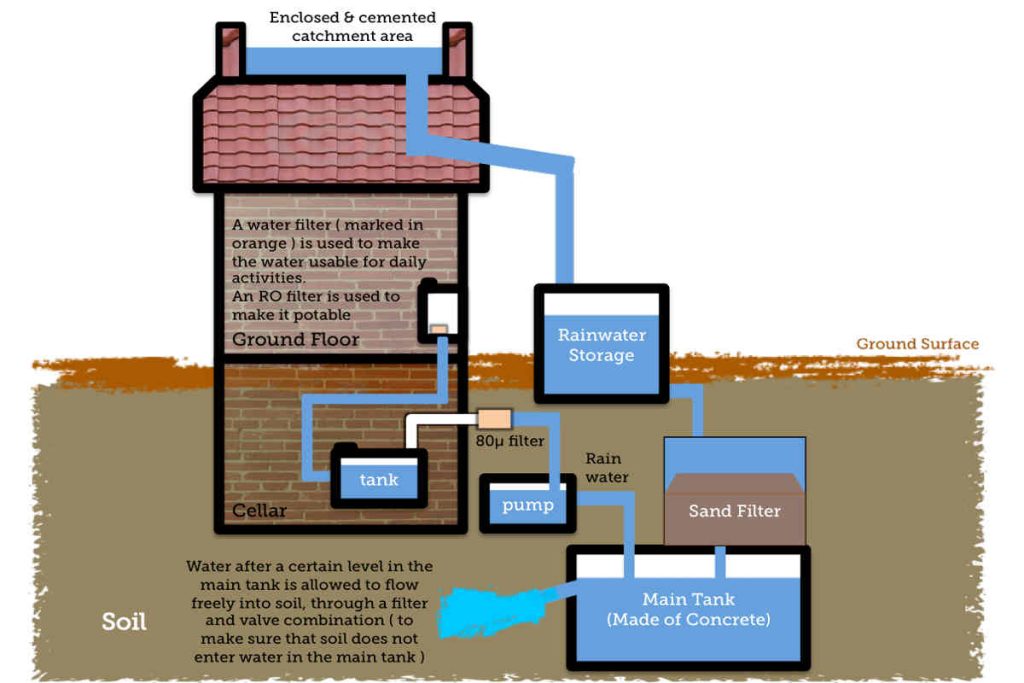

The scope of decentralised systems can be broad. They may include rooftop rainwater harvesting, greywater recycling for non-potable use, decentralised wastewater treatment units, or stormwater infiltration structures. In fast-growing urban areas, they can serve areas that centralised networks do not reach. In dense metros, they can reduce pressure on ageing infrastructure by treating and reusing water locally.

Why Decentralisation Matters

Decentralisation matters because it enhances resilience, reduces losses, and improves efficiency. When water is treated and reused closer to its source, cities save the energy and money spent on transporting large volumes through long pipelines. EPA research shows that decentralised systems often reduce infrastructure costs and offer quicker installation timelines because they do not require extensive underground networks.

Decentralised systems also help cities cope with climate stress. As rainfall becomes more erratic, local harvesting and reuse provide a buffer against shortages. Studies of low-impact development models in Asian cities show that decentralised stormwater structures reduce flooding and help recharge aquifers during heavy rains. In neighbourhoods with declining groundwater, decentralised recharge and reuse reduce extraction pressure while improving local availability.

In many cases, decentralisation complements rather than replaces centralised systems. It fills the gaps where large networks struggle. It strengthens a city’s ability to adapt, treat, reuse, and manage water sustainably. Most importantly, it shifts the urban water model from a linear system to a circular one where water is used more than once and handled responsibly at every stage.

If these principles sound relevant to your city, the next section will help you recognise the warning signs that a decentralised approach has become essential.

11 Signs Your City Needs a Decentralised Water Management System

Sign 1:Persistent Water Scarcity and Groundwater Depletion

Water scarcity is one of the clearest indicators that a city’s centralised system is no longer keeping up with demand. When reservoirs drop early in the season, or when groundwater levels dip deeper each year, it suggests that the existing supply infrastructure cannot match the pace of urban growth. In many cities, this scarcity becomes visible long before policymakers acknowledge the crisis. Residents begin relying on tankers. Industries schedule water deliveries. Households store water in rooftop tanks for fear of irregular supply. These behavioural changes reflect systemic stress.

Centralised systems often struggle because they depend on single large sources such as rivers or distant dams. As climate patterns shift, these sources become unreliable. Drought years become longer and more frequent, leaving cities exposed. Meanwhile, the pipeline networks pulling water from these faraway sources face additional losses during transport. This creates a situation where even when water is available at the source, much of it is lost before reaching consumers.

Groundwater depletion is an equally important signal. Across India, the Central Ground Water Board has repeatedly noted falling water tables in major urban regions. Cities extract far more groundwater than they recharge. When this happens year after year, it reflects a structural imbalance. A decentralised water management system helps correct this trend by promoting local treatment and reuse. It reduces pressure on groundwater and supports recharge through decentralised stormwater systems, permeable surfaces, and community-based harvesting structures.

Research from multiple urban studies, including analyses by Indian planning bodies, shows that many towns struggle to finance full centralised treatment and supply. Local decentralised units, especially for wastewater treatment and reuse, help close the supply gap by converting what was once waste into a usable resource. For cities where water scarcity has become an annual crisis, decentralisation is no longer an option but a necessity.

Sign 2: High Non Revenue Water and Leakage Losses

One of the most visible signs of a struggling centralised water system is the volume of water that disappears before reaching consumers. This loss, known as non revenue water, includes leaks in ageing pipelines, unauthorised connections, inaccurate metering, and distribution inefficiencies. When a city loses a significant share of its treated water, it signals that the supply network is overstretched and unable to maintain its integrity.

Many Indian cities report non revenue water levels above thirty percent. In some metropolitan regions, the losses are even higher. These losses represent more than missing water. They indicate the high cost of maintaining long and complex distribution systems that run underneath congested urban areas. Repairing these networks often requires extensive excavation, repeated shutdowns, and heavy financial investment. As cities expand outward, the length of pipelines increases and the risk of leakage grows with it.

Studies from water management organisations show that decentralised systems help reduce non revenue water by shortening the distance between treatment and end use. When water is treated locally, it does not need to travel through kilometres of pipelines. Smaller networks are easier to manage and repair. They are less vulnerable to sudden bursts, pressure failures, or corrosion. This approach prevents the loss of expensive treated water and improves the financial sustainability of local utilities.

High leakage rates also undermine trust in the public water system. When households see water pooling on streets due to broken pipes while their own taps run dry, confidence erodes. A decentralised network helps restore balance by strengthening local reliability. Treated water can be reused within the community for gardening, flushing, or industrial processes. This reduces the pressure on the central system and lowers overall demand.

Cities with persistent leakage issues often spend large sums repairing their networks without addressing the root of the problem. Decentralisation offers a structural solution that prevents losses rather than continually patching old pipes. When non revenue water becomes a constant budget burden, it is a clear sign that the city must adopt a more distributed approach to water management.

Sign 3: Frequent Urban Flooding and Inadequate Stormwater Drainage

Urban flooding has become a recurring feature of many modern cities. A short spell of intense rain is often enough to overwhelm drains, choke streets, and bring traffic to a standstill. When this pattern repeats year after year, it reveals a deeper structural issue. The centralised stormwater systems that many cities rely on were built for a different era. They were designed for predictable rainfall patterns, lower population density, and more permeable ground surfaces. Today’s climate conditions and urban forms are very different.

Rapid urbanisation has replaced open land with concrete, leaving very little surface area for water to naturally infiltrate into the soil. As a result, even moderate rainfall produces large amounts of runoff. Traditional drainage networks cannot handle this sudden surge. The problem intensifies during cloudbursts, which are becoming more common as climate change accelerates. These short, sharp rainfall events deliver several days’ worth of water in just a few hours. Centralised drainage systems with fixed capacity find themselves overwhelmed almost instantly.

Decentralised stormwater management offers a more adaptive response. Instead of depending only on large drains and central outfalls, it spreads water management across multiple smaller structures. These include local recharge pits, permeable pavements, bioswales, rain gardens, and rooftop harvesting systems. Research on low impact development models shows that these decentralised solutions reduce peak runoff, lower flood levels, and help recharge depleted aquifers. By holding and absorbing water locally, decentralised systems ease pressure on the main drainage network.

Cities that adopt decentralised models often see two simultaneous benefits. Flooding reduces because water is slowed down and absorbed before it reaches the drains. Water availability improves because a portion of the captured rain replenishes local groundwater. This dual impact is especially helpful in regions where flooding and water scarcity occur within the same year.

Frequent flooding is not just a monsoon problem. It reflects a mismatch between current rainfall behaviour and outdated drainage infrastructure. When residents begin expecting waterlogging as a normal event or when businesses suffer repeated monsoon losses, the city is receiving a clear message. It needs stormwater systems that can adapt to climate realities. Decentralised structures provide the flexibility and responsiveness that large central networks simply cannot deliver alone.

Sign 4: Ageing Centralised Infrastructure and Rising Maintenance Costs

In many cities, the water infrastructure running beneath the streets is older than the buildings above it. Pipelines laid decades ago, treatment plants operating past their designed capacity, and outdated pumping systems are all part of a decaying foundation that urban growth continues to lean on. As this centralised infrastructure ages, the cost of maintaining it rises sharply and so does the frequency of breakdowns.

Ageing infrastructure is not just an engineering issue. It becomes a financial, social, and environmental liability. Repairing large pipelines that traverse busy roads requires heavy machinery, traffic diversions, and days, sometimes weeks of disruption. Treating water at a central plant with worn-out parts leads to declining output quality and efficiency. These challenges become particularly acute in cities with expanding populations, where old networks are asked to serve far more people than they were ever built for.

A study by the Community Sewer System in the United States found that decentralised treatment systems can significantly reduce long-term operational costs by eliminating the need for costly central pumping and distribution. Instead of pumping water across kilometres to a central location, decentralised units treat and reuse water on-site or nearby. This reduces energy consumption, delays the need for expensive overhauls, and allows for modular upgrades as needed.

From a fiscal perspective, decentralised systems are also more adaptable. While a single central plant requires a large up-front investment, decentralised units can be installed in phases and scaled according to local demand. Maintenance is also easier. A fault in a localised unit affects only a small service area, not the entire city. Repairs are quicker, less expensive, and less disruptive.

Cities like Bengaluru and Chennai have faced repeated crises due to outdated and overloaded centralised sewage and water infrastructure. In some cases, the cost of upgrading the entire system runs into thousands of crores. Yet, decentralised pilot projects in select neighbourhoods have shown promise in easing the burden on central plants and extending the system’s overall life.

When maintenance budgets keep rising without visible improvements, or when breakdowns become routine rather than exceptional, it’s a sign the system is ageing beyond repair. Decentralised water management offers a way to reduce this pressure, extend the life of core infrastructure, and distribute the responsibility for water services more sustainably.

Sign 5: Limited Capacity for Expansion of Centralised Sewer or Water Systems

Cities grow faster than their infrastructure. New neighbourhoods appear on the outskirts, apartment complexes rise on former farmland, and informal settlements expand along the edges of highways and industrial zones. But the centralised water and sewer systems that are meant to serve these areas often cannot keep up. When a city struggles to extend pipelines or connect new communities to its main network, it signals structural limits in the centralised model.

Centralised systems are built around fixed capacities. Treatment plants can handle only a certain volume before quality begins to decline. Pumping stations have limits on distance and elevation. Pipelines require specific pressure levels to function effectively. As cities sprawl outward, these constraints become more visible. Local governments face a reality where expanding the central network requires massive investments, difficult land acquisition, and years of construction. Even then, the extended systems may still not perform efficiently.

This challenge becomes more pronounced in regions with unplanned or rapid development. Informal settlements, for example, often emerge faster than municipal planning cycles. Since centralised networks involve long, rigid pipelines, connecting these communities becomes both costly and technically difficult. A study on decentralised urban water management in Indian states observed that centralised systems would be unaffordable for large portions of rapidly growing populations. The infrastructure required to extend coverage would exceed municipal budgets and take too long to install.

Decentralised systems offer a practical alternative. Small-scale treatment units, modular water recycling plants, and localised sewer networks can be installed near the communities they serve. These systems do not require long pipelines or complex pumping arrangements. They fit well in dense areas where laying new pipelines is challenging and in newly developing areas where central connections are not yet available. Such systems also help reduce the load on the main network by treating water locally and recycling it for non-potable uses.

In many Indian cities, large apartment clusters and gated communities have already adopted decentralised sewage treatment plants to bridge gaps in municipal services. These systems allow residents to manage wastewater locally, reuse treated water for landscaping or flushing, and reduce demand on the city’s central plant. Similar models are emerging in industrial areas where decentralised treatment makes operations more reliable and less dependent on fluctuating municipal supplies.

When a city reaches a point where connecting new developments to central pipelines is no longer feasible, practical, or affordable, decentralised systems become essential tools for sustainable growth. They allow cities to expand without collapsing under the burden of infrastructure extensions.

Sign 6: Increasing Demand for Local Water Reuse and Circular Water Economy

As cities grow, the pressure on freshwater sources intensifies. Climate variability, rising temperatures and unpredictable monsoons make water availability even more uncertain. In this environment, local water reuse becomes essential. When a city starts depending heavily on recycled water or when industries and institutions begin seeking reliable reuse options, it is a clear sign that decentralised systems are needed.

Urban planners and sustainability experts increasingly advocate for a circular water economy. This approach treats water not as a single use resource but as part of a continuous loop. Wastewater can be processed, polished and reused for multiple non potable purposes. These include flushing, cooling, landscaping and industrial applications. Research on decentralised membrane bioreactors shows that these systems offer stable, high quality treated water suitable for many reuse needs. When treatment happens close to where water is consumed, the reuse cycle becomes efficient and cost effective.

Cities with rising water stress often see industries move toward decentralised reuse to avoid operational downtime. Hotels, tech parks and residential complexes adopt local treatment units to secure their own supply. This shift reflects both a demand for reliability and a recognition of the limits of centralised systems. When entire sectors begin to look beyond municipal networks for sustained supply, the gap between demand and capacity becomes visible.

Centralised systems struggle with reuse because they are designed to transport water over long distances. Returning treated water from a central plant to users requires another set of pipelines, pumps and reservoirs. This makes city wide reuse complex and expensive. Decentralised systems bypass this challenge. Treated water can be used immediately at the source, reducing both conveyance needs and energy costs. This model also improves the financial viability of treatment by lowering operational expenses.

The growing emphasis on sustainability goals and environmental compliance strengthens the need for decentralised reuse. Water intensive sectors face regulatory pressure to reduce consumption. Decentralised systems provide a dependable way to meet these targets while cutting waste. They also reduce the environmental footprint of cities by lowering extraction rates and improving the quality of discharged water.

When a city experiences rising interest in reuse from residents, industries and institutions, it signals a structural need for decentralisation. Localised systems become key to meeting demand and building a circular water future.

Sign 7: Rapid Urbanisation, Informal Settlements and Low Infrastructure Density

Cities experiencing rapid urbanisation often struggle to extend essential services at the same pace as population growth. New residential blocks, peri urban developments and expanding informal settlements place enormous pressure on centralised water and sewer systems. When a city grows faster than its infrastructure, gaps emerge. These gaps become visible in the form of unserved neighbourhoods, tanker dependence and localised pollution from untreated wastewater.

Informal settlements highlight this challenge more than any other urban form. They tend to develop outside planned layouts, on marginal land or in areas not covered by municipal pipelines. Since centralised systems depend on long, continuous networks, reaching these settlements becomes technically difficult and financially demanding. Digging trenches, laying pipelines and installing pumping stations in dense, unplanned areas often proves impossible. Even when attempted, the cost far exceeds municipal budgets.

International and Indian studies on decentralised wastewater treatment show that decentralised systems are well suited to such environments. Community level treatment units, modular plants and cluster based networks can serve settlements that centralised pipelines cannot reach. These systems do not require long distribution lines or heavy construction. They can be installed in compact spaces, operate with lower energy needs and offer reliable service to communities that would otherwise remain excluded.

Urban growth also reduces the natural capacity of land to absorb water. As concrete replaces soil, groundwater recharge declines. Informal settlements often suffer the most because they sit in low lying areas or on land with limited drainage. Local decentralised solutions such as recharge pits, biofilters and rainwater harvesting systems help improve both water availability and wastewater management in these areas. They strengthen resilience without waiting for large network expansions that may never arrive.

Cities like Mumbai, Delhi and Hyderabad show clear examples of this pattern. While central networks serve the core city, the peripheries depend on small, localised systems. These areas often implement decentralised sewage treatment, groundwater recharge and rainwater harvesting out of necessity. Such approaches reduce pressure on the main city systems and provide essential services to vulnerable populations.

When a city continues to expand outward but its centralised networks fail to follow, decentralisation becomes not only practical but urgent. It allows cities to offer equitable services, protect public health and maintain environmental quality even in areas where traditional infrastructure cannot reach.

Sign 8: Water Quality Challenges: Pollution, Source Contamination and Poor Treatment

A city’s water quality tells a deeper story about how well its infrastructure is functioning. When tap water becomes unreliable, when rivers turn foamy or toxic, or when untreated sewage flows into local lakes, it signals a breakdown that centralised systems alone can no longer manage. Water pollution is often treated as an environmental issue, but in reality, it is an infrastructure warning. It shows that the city’s treatment capacity is falling behind its waste generation.

In many urban regions, centralised wastewater plants operate far beyond their designed limits. As populations grow and sewage volumes rise, these plants struggle to treat wastewater effectively. The result is partially treated or untreated water being discharged into water bodies. This degrades local ecosystems, contaminates groundwater, and reduces the availability of clean water for the city itself. When contamination becomes widespread, cities lose safe sources more quickly than they can find new ones.

Research on decentralised systems in Southeast Asian cities shows how localised treatment improves water quality by preventing sewage from entering rivers and lakes. A case study from Yangon highlighted how neighbourhood based treatment units helped improve environmental conditions and provided communities with a more reliable form of wastewater management. Since decentralised plants serve smaller catchments, the treated water is consistent, and system failures are easier to identify and resolve.

Pollution from stormwater runoff also adds pressure. When rainfall washes oil, waste and industrial residue into drains, centralised plants must handle fluctuating loads that were never factored into their design. Decentralised stormwater structures such as biofilters and sediment tanks reduce this burden by cleaning water before it reaches larger drains or water bodies. This gradual, distributed filtering system improves urban water quality and supports healthier waterways.

Source contamination is another warning sign. When lakes become eutrophic or when groundwater shows rising levels of ammonia, nitrates or bacterial contamination, it means the city can no longer rely on its traditional sources. Centralised systems struggle to treat heavily polluted water because it requires higher operating costs, increased energy and complex technology. Localised units, on the other hand, can treat wastewater at its origin, preventing contaminants from spreading across the city.

Communities often notice these quality issues long before governments act. Households begin depending on filters, boiling water regularly or purchasing drinking water. These small behavioural shifts reflect a bigger systemic failure. When a city reaches a point where clean water requires individual protection measures, it is a clear indicator that decentralised treatment and pollution prevention systems must be integrated into its water strategy.

Sign 9: Pressure to Meet Sustainability and Resilience Goals and Climate Change Impacts

Cities today operate under a new level of climate pressure. Rainfall patterns are shifting, drought cycles are becoming longer, and heat waves are intensifying. These changes are not abstract projections. They are already shaping how cities plan, build and survive. When a city begins struggling to meet sustainability commitments, or when climate risks start disrupting water supply and sanitation, it is a clear sign that centralised systems alone are no longer adequate.

Centralised water infrastructure is built on predictability. It assumes steady rainfall, consistent river flows and gradual population growth. Climate change breaks all these assumptions. Sudden storms overwhelm drains, long dry periods deplete reservoirs and rising temperatures increase daily water demand. Under these conditions, centralised systems face stress from both ends. They must stretch their supply during droughts and protect themselves from floods during extreme rainfall. Few systems can manage both without additional support.

Global and national sustainability frameworks increasingly emphasise decentralised water action. The Sustainable Development Goals encourage cities to adopt water reuse, improve local recharge and reduce untreated wastewater. Climate resilience guidance from international research bodies also highlights the role of distributed systems that reduce dependency on single sources. These recommendations are grounded in practical performance. Decentralised systems respond faster, adapt more easily and limit the scale of failure during extreme events.

A decentralised approach strengthens resilience because it creates multiple nodes of supply and treatment. If one unit fails during a climate event, others continue to operate. Local wastewater treatment reduces pollution risks during heavy rains. Rainwater harvesting slows runoff and reduces the intensity of flash floods. Local reuse systems keep essential activities functioning even when the main supply is interrupted. Together, these measures create a flexible network that supports the city during climate stress.

Cities that commit to sustainability targets often find that decentralised systems help them meet regulations more effectively. Reducing groundwater extraction, improving wastewater treatment quality and increasing reuse are all easier when managed at a local scale. Industrial clusters, housing societies and public institutions that adopt decentralised systems contribute directly to citywide climate goals without adding pressure to the main network.

When climate shocks begin to affect water availability or when a city struggles to meet environmental targets despite major investments, it signals the need for a decentralised shift. These systems provide the resilience and adaptability that modern climate conditions demand.

Sign 10: Lack of Financial Viability of Large Central Projects

As cities grow, the cost of building and maintaining large centralised water infrastructure rises sharply. Treatment plants, long-distance pipelines, pumping stations and large sewer networks demand huge capital investment. When a city starts postponing upgrades or delaying new projects because of financial constraints, it signals that the traditional centralised approach is reaching its economic limits.

Centralised projects require substantial upfront spending. They also involve costs related to land acquisition, environmental approvals and long construction timelines. For many municipalities, these expenses exceed annual budgets. Even when funding is secured, the return on investment takes years to materialise, making such projects difficult to justify in rapidly changing urban environments. A report shared in a United States Environmental Protection Agency webinar highlighted how decentralised systems avoid many of these expenses by minimising distribution distances and reducing the need for heavy infrastructure.

Operating large plants also creates recurring financial burdens. Energy consumption is high, trained personnel are needed, and maintenance schedules are demanding. As infrastructure ages, these costs rise even further. Cities often end up spending more on repairs than on improving services. When the financial strain increases without a matching improvement in water quality or availability, it becomes evident that the model needs rethinking.

Decentralised systems offer a more flexible financial pathway. They can be installed in phases, scaled based on demand and upgraded gradually. Because they operate closer to users, they require far fewer pipelines and pumping stations. This reduces both capital expenditure and operational costs. For example, local wastewater treatment units in residential or industrial clusters eliminate the need to transport large volumes of sewage across the city, saving money and reducing the risk of system overload.

Private developers and institutions also play a crucial role. When decentralised systems are adopted by housing societies, campuses, factories and commercial complexes, they share responsibility with municipal bodies. This reduces the financial burden on city authorities and allows public funds to be directed toward areas with the greatest need.

Cities facing repeated budget shortfalls for centralised water projects often reach a tipping point where decentralisation becomes the only viable option. By lowering costs, distributing financial responsibility and improving efficiency, decentralised systems create a more sustainable economic model for future water management.

Sign 11: Community Demand, Local Capacity and Decentralised Governance Opportunities

A city’s shift toward decentralised water management often begins from the ground up. When residents, neighbourhood associations, institutions and local leaders start demanding reliable water solutions, it signals both a loss of confidence in central systems and a readiness to participate in alternatives. This growing civic engagement becomes a powerful indicator that decentralised systems are not only appropriate but necessary.

Communities tend to recognise gaps in water services earlier than policymakers. They feel the impact of shortages, contamination and unreliable supply every day. As a result, many neighbourhoods adopt their own small scale responses such as rainwater harvesting, local treatment units or community run recharge structures. These initiatives show that citizens are aware of the limits of central systems and are prepared to take responsibility for part of the solution.

Local capacity also plays a central role. When technical knowledge, trained professionals and private providers become available within the city, they create favourable conditions for decentralised systems. Urban local bodies often collaborate with private operators to manage decentralised wastewater treatments, rooftop harvesting systems and cluster based reuse facilities. This shared responsibility strengthens resilience and improves service delivery without overburdening municipal agencies.

Decentralised governance models in water management are increasingly recognised in global sustainability discussions. Studies and policy papers highlight how decentralised approaches promote transparency, accountability and community ownership. They also reduce delays because decisions are made closer to the users. When residents participate in planning, monitoring and maintaining local systems, water management becomes more adaptive and responsive.

This shift is visible in many Indian cities. Housing societies manage their own sewage treatment plants. Industrial estates operate decentralised reuse facilities to secure reliable supply. Schools and universities install their own rainwater harvesting systems and promote conservation practices. Each of these efforts reduces pressure on the citywide network and creates a shared pathway toward sustainability.

When communities show willingness to co manage water resources and when local governance structures begin supporting these efforts, it signals a strong opportunity for decentralised water management. This alignment between public demand and local capacity provides the foundation for a long term, resilient and inclusive water strategy.

Case Studies: Cities Moving to Decentralised Water Systems

Case Study 1: Urban Water Management in Indore, India

Indore has emerged as one of India’s strongest examples of how decentralised interventions can strengthen urban water systems. The city faced mounting pressure from rapid population growth, wastewater discharge and shrinking water sources. For years, untreated sewage flowed into canals and local water bodies, deteriorating both public health and environmental conditions. The centralised sewage system could not handle the increasing volume, and expanding the main treatment plants would have required heavy investment and long construction timelines.

Instead of depending solely on large facilities, Indore adopted a hybrid model that included multiple decentralised wastewater treatment units across the city. These smaller plants were strategically located near key drainage points and dense settlements. This allowed sewage to be treated locally before it entered natural water bodies. Treated water was reused for landscaping, construction and non potable industrial needs, easing pressure on freshwater sources.

Indore also implemented decentralised solid waste and stormwater measures that complemented its water initiatives. Local composting centres reduced the load on the central landfill, while community level stormwater structures helped improve groundwater recharge. These combined efforts supported the city’s wider resilience goals.

A report on decentralised urban water management shared through national policy research platforms highlights that cities like Indore achieved better compliance with environmental norms by adopting localised treatment systems. These systems helped the city meet the requirements for a “water plus” rating, which recognises urban regions that treat and reuse their wastewater effectively.

The Indore example shows that decentralised systems are not just supplementary but transformative. They strengthen the main network, protect water bodies and create a more reliable cycle of treatment and reuse. Indore’s approach demonstrates that even a fast growing city can improve its water management by distributing the responsibility across multiple smaller units.

Case Study 2: DEWATS in Yangon, Myanmar

Yangon offers a compelling example of how decentralised wastewater treatment can address urban sanitation challenges in rapidly growing cities. As Myanmar’s largest urban centre, Yangon faced significant pressure from rising populations, limited sewer coverage and ageing drainage networks. Large sections of the city lacked access to centralised wastewater systems, resulting in untreated sewage flowing into local waterways and contributing to widespread pollution.

To address these issues, parts of Yangon adopted the Decentralised Wastewater Treatment System (DEWATS) model. DEWATS is designed to operate without heavy mechanical components, relying instead on natural treatment processes. These systems treat wastewater at the community or neighbourhood level and are well suited to developing urban areas where centralised infrastructure is either unaffordable or physically difficult to install.

Research published by sustainability scholars documented the performance of DEWATS units in Yangon. The findings showed that decentralised systems provided consistent treatment quality and operated with lower energy consumption. Because they serve smaller catchments, the systems were easier to maintain. Localised treatment also reduced pollution in surrounding canals and helped improve the health of vulnerable communities living near contaminated water bodies.

One of the key strengths of Yangon’s decentralised approach was its adaptability. DEWATS units were installed in schools, informal settlements and mixed use neighbourhoods where central sewer networks did not exist. The modular design allowed the city to expand coverage gradually, without waiting for large centralised infrastructure upgrades. These systems improved sanitation access and protected urban waterways, providing long term environmental benefits.

The Yangon case also highlights the importance of community involvement. Local households participated in monitoring and maintenance, creating a sense of ownership that strengthened system reliability. This governance structure ensured that the decentralised plants remained operational and responsive to local needs.

Yangon’s experience demonstrates how decentralised wastewater treatment can bridge the service gap in growing cities. It shows that localised systems can deliver environmental, social and technical benefits even in resource constrained settings.

Case Study 3: Industrial Reuse Case in Israel (Decentralised MBR)

Israel has long been recognised as a global leader in water reuse, and one of the reasons behind its success is the adoption of decentralised treatment technologies in industrial zones. As industries expanded and water demand rose, many facilities found that relying solely on municipal supply was no longer sustainable. Seasonal shortages, rising costs and strict environmental regulations pushed them to find more reliable and efficient solutions. This led to the adoption of decentralised membrane bioreactor (MBR) systems for onsite treatment and reuse.

In several industrial areas, decentralised MBR plants were installed to manage wastewater directly at the source. These compact, modular units treat industrial effluent to a high standard, allowing the water to be reused for non potable purposes such as cooling, cleaning and landscape irrigation. Because the treatment happens onsite, industries avoid the need to transport large volumes of wastewater to central facilities. This reduces both conveyance costs and the risk of overloading municipal systems.

A documented case from an Israeli industrial facility showed how decentralised MBR technology helped the plant achieve stable, high quality treated water suitable for continuous reuse. The system operated with lower energy costs compared to transporting wastewater long distances and offered greater reliability during periods of scarcity. By recycling its own wastewater, the facility reduced its dependence on freshwater sources and contributed to the wider national goal of efficient water use.

The decentralised approach also proved beneficial from a regulatory standpoint. Environmental authorities in Israel encourage industries to reduce their wastewater discharge, and onsite treatment helped companies meet compliance targets. MBR systems are known for producing consistent output, even when influent quality fluctuates. This stability made it easier for industries to maintain environmental standards and avoid penalties.

Israel’s experience underscores the economic and operational value of decentralised systems in high demand sectors. These systems provide greater control, reduce vulnerability to municipal shortages and support circular water practices. The success of decentralised MBR in industrial settings demonstrates how local treatment can complement national efforts, strengthen resilience and reduce strain on citywide infrastructure.

Policy and Planning Implications

Cities that recognise the signs of water stress face an urgent question: how should they redesign their systems to meet present and future needs? Transitioning toward decentralised water management is not only a technical shift but also a policy transformation. It requires changes in governance, financing, planning and public participation

What Urban Planners and Local Bodies Must Consider

Urban planners stand at the centre of the transition to decentralised water systems. Their decisions shape how cities grow, how water flows and how communities access essential services. When planners rely solely on centralised infrastructure, they often face delays, cost overruns and limited flexibility. A decentralised model offers new planning pathways but requires thoughtful integration into the existing urban fabric.

The first priority for planners is to map water demand and wastewater generation at a granular level. Decentralised systems depend on understanding neighbourhood patterns rather than citywide averages. This requires updated surveys, digital mapping tools and real time monitoring frameworks. When planners identify high density clusters or rapidly growing corridors, they can place modular treatment units and reuse systems where they are most effective.

Local bodies must also build regulatory frameworks that allow decentralised systems to operate smoothly. This includes approval processes for on site treatment plants, guidelines for treated water reuse and standards for discharge quality. Clear regulations help ensure that decentralised units deliver reliable performance and remain aligned with citywide environmental goals.

Financing mechanisms need equal attention. Municipal budgets often prioritise large central projects, while decentralised units require new models of cost sharing. Public private partnerships, community financing, corporate participation and developer obligations can help distribute costs. These frameworks allow decentralised systems to grow organically without waiting for large capital allocations.

Capacity building is another crucial element. Engineers, operators and planners must be trained to design, manage and maintain decentralised technologies. Without technical knowledge, systems may fail or fall into disuse. Cities that invest in training programs, workshops and partnerships with research institutions strengthen their long term resilience.

Urban design itself must evolve. Planners can integrate decentralised water features into parks, public buildings, transport hubs and residential neighbourhoods. Rain gardens, bioswales, recharge pits and decentralised treatment plants can be part of broader urban regeneration projects. When water systems blend into the city’s natural and built environment, they become more accessible, transparent and easier to maintain.

In short, decentralisation requires planners to shift from a one size fits all approach to a flexible, layered strategy. When planning adapts to local needs, water management becomes more efficient, inclusive and sustainable.

How Decentralised Systems Fit into National and Global Water Policy

Decentralised water management is no longer viewed as an alternative experiment. It is now recognised as a core part of national and global sustainability goals. As countries confront climate risks, rising urban populations and shrinking water sources, policy frameworks increasingly support systems that treat, reuse and recharge water locally. When a city aligns itself with these policies, it not only strengthens its own resilience but also contributes to national and international commitments.

At the national level, several Indian policy documents emphasise the importance of decentralised approaches. Urban development guidelines encourage rainwater harvesting, local reuse and on site wastewater treatment. Environmental regulations require large residential complexes, commercial buildings and industries to install their own treatment units and ensure that treated water is reused or safely discharged. These rules reflect a broader shift away from total dependence on municipal systems and toward shared responsibility between public and private actors.

Decentralised systems also align strongly with India’s goals under the Sustainable Development Agenda. The targets for clean water, sanitation and climate resilience highlight the need for cities to adopt efficient, inclusive and adaptive water systems. Local treatment and reuse help reduce demand on freshwater sources and improve environmental quality. By preventing untreated wastewater from entering rivers and lakes, decentralised systems support the country’s wider goals for ecosystem protection and water security.

Globally, the push toward circular economy models reinforces the value of decentralised solutions. International research bodies and policy coalitions advocate for reducing water loss, improving reuse and strengthening local resilience. These recommendations are based on the recognition that large, centralised systems alone cannot handle the scale and speed of today’s urban challenges. Localised units provide agility, redundancy and adaptability, qualities that global frameworks now prioritise.

Decentralised systems also support climate adaptation strategies. They help cities respond to extreme rainfall, prolonged droughts and rising temperatures without relying entirely on centralised infrastructure. Localised recharge, treatment and reuse create a network of small but robust nodes that can stabilise a city during climate shocks. Many global climate action plans encourage cities to adopt these distributed systems to reduce vulnerability and improve long term sustainability.

For urban policymakers, aligning with these national and international frameworks brings several advantages. It unlocks funding opportunities, strengthens compliance with environmental norms and demonstrates commitment to sustainable urban development. When a city adopts decentralised systems, it positions itself within a broader global movement toward responsible water stewardship.

Barriers to Adoption and How to Overcome Them

While the benefits of decentralised water systems are clear, many cities still hesitate to adopt them. The reasons are complex. They include technical uncertainty, governance challenges, financial constraints and public perception issues. Understanding these barriers is essential for designing policies that support long term, sustainable decentralised solutions. Overcoming them requires coordinated action across stakeholders, institutions and communities.

One of the biggest challenges is technical capacity. Decentralised systems demand local expertise for design, operation and maintenance. Without trained personnel, cities may worry about system failures or inconsistent performance. To overcome this, many successful cities invest in capacity building. Partnerships with universities, training institutes and private operators create a talent pool that can manage decentralised technologies effectively. Workshops, certification programs and knowledge exchanges help build confidence among municipal engineers and planners.

Regulatory gaps also slow adoption. Existing policies in many cities were created with large centralised systems in mind. They often lack clear guidelines for approving, monitoring and governing decentralised plants. This creates hesitation among developers and operators. Updating regulations to include standards for treated water quality, reuse guidelines and compliance mechanisms helps create a stable environment for decentralised systems. Transparent rules make it easier for households, institutions and industries to invest in local solutions.

Financial barriers can be equally significant. Decentralised systems require upfront investment, even if their long term costs are lower. Many communities, especially in low income areas, struggle to finance such projects. Cities can address this through incentives, subsidies and cost sharing models. Public private partnerships, corporate social responsibility funds and community financing arrangements can all support decentralised installations. When financial models are flexible, decentralised systems become more accessible.

Public perception is another obstacle. Some residents are sceptical about the quality of treated water from decentralised plants, especially when it is used for reuse. Awareness campaigns, transparent reporting and community involvement can overcome this. When citizens see treatment units operating efficiently or when they observe the benefits of reduced flooding and improved groundwater, trust grows naturally.

Coordination between agencies is also essential. Water, sanitation, planning and environmental departments must work together. Fragmented responsibilities often slow the rollout of decentralised systems. Cities that develop integrated water management plans experience smoother transitions. A unified strategy helps align budgets, regulations and operational priorities.

Overcoming these barriers requires persistence. But the rewards are significant. Cities that invest in decentralised systems strengthen their resilience, reduce pressure on central infrastructure and move closer to sustainable urban water management.

Future Outlook and Recommendations

Cities across the world are entering a decisive phase in their water management journey. Climate risks are intensifying, urban populations are rising, and traditional infrastructure is reaching its limits. In this changing landscape, decentralised water systems are no longer optional. They are essential tools for building the resilient, inclusive and sustainable cities of the future.

Cities that successfully integrate decentralised water systems tend to combine long term planning with flexible, localised action. They recognise that centralised plants will continue to play an important role, but they also understand that no single system can carry the full load in a climate stressed future. Decentralised systems provide the adaptability required to navigate unpredictable conditions. They allow cities to distribute risk, protect local water bodies and secure reliable supplies even during crises.

Looking ahead, the most successful urban water strategies will adopt a hybrid model. Centralised plants will manage large volumes and ensure baseline quality. Decentralised units will handle localised flows, improve reuse and strengthen resilience. Together, they will create a multi layered system that can respond to both long term trends and sudden shocks. This approach also supports circular water practices, where wastewater becomes a resource and rainwater becomes an asset.

To move toward this future, cities must prioritise three actions. The first is investing in data. Accurate, neighbourhood level information on water demand, wastewater generation, leakages and groundwater levels is essential for planning decentralised infrastructure. Smart meters, sensors and digital mapping tools help cities monitor their systems more effectively and identify hotspots where local solutions are most needed.

The second action is enabling policy reform. Cities need clear regulations for reuse, discharge, quality standards and operational responsibilities. Strong governance frameworks provide confidence to developers, communities and private operators. They also help ensure long term compliance, which is vital for environmental protection and public health.

The third action is building public participation. Communities are at the heart of decentralised systems. When residents participate in planning and monitoring, the systems are more likely to succeed. Local ownership improves maintenance and boosts trust in the quality of treated water. Public awareness campaigns, school programs, open data dashboards and community consultations help embed decentralisation into urban culture.

The future of urban water management will depend on collaboration. Governments must work with communities, industries, technology providers and research institutions. Shared responsibility will allow cities to distribute the financial and operational load more fairly. It also encourages innovation, making room for new technologies such as compact MBRs, smart recharge systems and decentralised digital twins.

A decentralised future is not only technically feasible but also financially and socially advantageous. Cities that begin this transition today will be better equipped to face tomorrow’s uncertainties. They will secure their water resources, protect their ecosystems and create healthier, more resilient communities.

A Final Thought

Cities today stand at a crossroads. Their traditional centralised water systems, once symbols of modern progress, are no longer capable of meeting the demands of fast growing populations, shifting climate patterns and expanding urban boundaries. The signs of strain are visible everywhere. Water scarcity appears earlier each year. Flooding becomes more frequent and disruptive. Infrastructure ages faster than it can be repaired. Pollution spreads through rivers, lakes and groundwater. These challenges reveal the limits of a model designed for a different era.

Decentralised water management offers a path forward. It does not replace centralised systems but strengthens them by distributing responsibility across neighbourhoods, institutions and industries. When water is treated, reused and managed closer to where it is consumed, cities become more resilient. They lose less water, protect local ecosystems and reduce their dependence on distant sources. Localised solutions also give communities a voice in managing their own resources, creating a sense of ownership that makes urban systems more responsive and transparent.

The case studies from Indore, Yangon and Israel illustrate how decentralised systems can succeed in very different settings. They show that localised treatment is not just a technical fix but a social and environmental solution. These cities improved their water quality, reduced pressure on central plants and strengthened resilience during climate stress. Their experiences offer practical lessons for other regions seeking sustainable models.

As cities evaluate the 11 warning signs outlined in this review, they must recognise that decentralisation is not an emergency response. It is a strategic choice. It prepares cities for long term challenges by creating flexible, layered systems that can adapt to change. It reduces financial strain, supports environmental goals and aligns with national and global sustainability frameworks. More importantly, it ensures that every community, regardless of its location or income level, has access to reliable water and sanitation services.

The shift toward decentralised water management is more than an infrastructure reform. It is a commitment to the future. Cities that embrace this transition will be better equipped to protect their residents, preserve their ecosystems and build resilience for the generations to come.

FAQs: 11 Signs Your City Needs a Decentralised Water Management System: Earth5R Urban Review

1. What is a decentralised water management system?

It is a localised way of treating, storing, and reusing water at neighbourhood or building level, instead of relying only on central plants.

2. Does decentralisation replace centralised systems?

No. It complements them and reduces their burden.

3. Why are centralised systems failing in many cities?

Ageing pipelines, rapid urbanisation, climate change, and rising water demand all stress existing networks.

4. Is decentralisation expensive?

Initial costs vary, but decentralised units reduce long-term operational costs and require less energy.

5. Can decentralised systems improve groundwater?

Yes. They support recharge and reduce extraction.

6. What role does reuse play?

Reuse reduces freshwater demand, stabilises supply, and supports circular water economies.

7. Can decentralised systems help during droughts?

Yes. They create multiple sources of treated and recycled water.

8. Do decentralised systems reduce floods?

Yes. Local infiltration and stormwater structures reduce urban flooding.

9. Are decentralised systems reliable?

When maintained properly, they provide consistent performance.

10. Can industries benefit?

Industries use decentralised MBRs for cooling, cleaning, and reuse.

11. Do decentralised systems reduce energy use?

Yes, because they minimise long-distance pumping.

12. Are decentralised systems eco-friendly?

They reduce pollution and protect natural ecosystems.

13. Can they work in informal settlements?

Yes. DEWATS and cluster systems are ideal for unplanned areas.

14. Do they improve public health?

By reducing sewage discharge, they reduce waterborne disease risks.

15. Will decentralisation help old cities?

Yes. It reduces pressure on ageing pipes and plants.

16. Who maintains decentralised systems?

Utilities, private operators, RWAs, industries, or local communities.

17. Is decentralised reuse safe?

When treated to standards, it is safe for non-potable uses.

18. Can decentralised systems scale?

Yes. They can expand gradually and adapt to changing needs.

19. What policy support is needed?

Clear standards for reuse, effluent quality, and system approvals.

20. Which cities can adopt decentralisation?

Any city facing scarcity, flooding, pollution, or rapid growth.

Build the Water-Secure City Your Future Depends On

Every city shows early warning signs before a crisis hits. The question is whether leaders choose to act. Decentralised water management is not a trend. It is a proven, practical, and essential tool for a climate-stressed world. If your city faces scarcity, pollution, flooding, or rising infrastructure costs, the time to decentralise is now.

Support neighborhood-level solutions. Advocate for reuse. Demand regulations that empower communities. Encourage industries and residential complexes to adopt decentralised systems. The future of your city’s water security depends on the decisions you make today.

Authored by – Sneha Reji