Part 1: The Turning Tide

India’s rivers are its ancient lifelines, weaving through the nation’s cultural, spiritual, and economic identity. For millennia, they have nurtured civilizations and supported millions.

In recent decades, however, this life-giving network has been strained to the breaking point. Rapid urbanization, unchecked industrial effluent, and mounting civic waste have transformed many of these sacred arteries into toxic drains.

The scale of the problem is staggering. Research from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has identified 351 polluted river stretches across the country. This is not a localized issue, but a systemic crisis demanding a national response.

Yet, beneath the surface of this grim data, a quiet but powerful tide is beginning to turn. A dual-engine movement is demonstrating, for the first time, that this degradation is not irreversible.

The first engine is the high-profile, top-down government mission. This is best exemplified by the Namami Gange Programme, an integrated conservation mission now recognized by the United Nations as a “World Restoration Flagship” for its ambitious scope.

The second, and arguably more agile, engine is a ground-up force of technology-driven citizen action. This new wave of activism goes far beyond traditional volunteer cleanups.

Pioneering this approach is the environmental group Earth5R. They are implementing a scalable framework built on a robust Public-Private-Community Partnership (PPCP).

The “Earth5R Insight” is that restoration cannot be a simple act of removing trash. It must be an economically and socially sustainable loop. Their model focuses on creating a circular economy by processing waste for value and empowering local communities as stakeholders.

This article will examine eight rivers that serve as scientific proof that this combined, dual-engine movement is working. We will look at the hard data, the ecological revival, and the community-led case studies that signal a new era of hope for India’s waterways.

Part 2: Defining “Working” – The Scientific and Ecological Metrics of Success

To claim a river cleanup is “working” requires moving beyond mere visual inspection. A riverbank cleared of plastic bags is a start, but it is not the standard. True success is invisible to the naked eye, hidden in the water’s chemical composition and the ecosystem it supports.

Just as doctors use vital signs to assess human health, environmental scientists use a core set of indicators to diagnose a river. These metrics provide an objective, research-driven answer to the question, “Is it getting better?”

The first and most critical vital sign is Dissolved Oxygen (DO). Think of DO as the river’s ability to breathe. Fish, insects, and healthy aquatic plants all require dissolved oxygen to survive. A high DO level is a sign of a healthy, dynamic system, while low levels create suffocating “dead zones.”

Directly related to this is Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD). BOD measures the amount of oxygen consumed by bacteria while decomposing organic waste, such as sewage or industrial effluent.

If DO is the river’s breath, BOD is the metabolic load placed upon it. A low BOD is ideal. It means the water is clean, and its oxygen is free to support life rather than being used up to break down pollutants.

The third critical metric is Fecal Coliform (FC). The presence of this bacteria is a direct indicator of contamination by human or animal waste. High FC levels signal a severe health risk and are a primary target for new sewage treatment plants.

While these chemical tests provide the “what,” the ultimate proof of success is the “who.” The most profound evidence of a river’s revival is the return of life.

When apex species, which are highly sensitive to pollution, reappear, it confirms the entire food chain beneath them is healing. This is the ecological evidence.

The celebrated return of the Gangetic Dolphin to stretches of the Ganga, or the sight of Gharials successfully breeding, is more than just a good news story. It is the final, irrefutable validation that India’s cleanup movement is, scientifically, working.

Part 3: The National Flagship – Top-Down Success

3.1 River 1: The Ganga – The National Mission Reverses the Tide

For decades, the Ganga, India’s most sacred river, has been a symbol of a painful paradox. It has been revered as a goddess yet simultaneously forced to absorb vast quantities of industrial effluent and domestic sewage from 11 states along its basin.

The response to this degradation was the Namami Gange Mission, a comprehensive, 20,000-crore rupee program launched to restore the river’s health. The mission’s integrated approach was so significant that the United Nations recognized it as one of the world’s top 10 restoration flagships.

The strategy’s backbone is infrastructure, a critical, if unglamorous, component of revival. The mission’s primary goal has been creating a vast network of Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) to intercept the pollution before it ever reaches the river.

As of late 2023, government data reported over 190 sewerage infrastructure projects sanctioned, significantly enhancing the national treatment capacity by thousands of Million Litres per Day (MLD). This is the hard engineering of revival, designed to stop the problem at its source.

Simultaneously, a crackdown on Grossly Polluting Industries (GPIs) has yielded measurable results. By enforcing compliance and mandating new effluent treatment technologies, the total BOD load from these industries has been significantly curtailed.

The scientific proof is now emerging from the water itself. CPCB monitoring data confirms that in previously critical stretches, such as from Haridwar to Kanpur, there are observable improvements. Water quality monitoring stations are reporting higher Dissolved Oxygen (DO) and lower Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) levels.

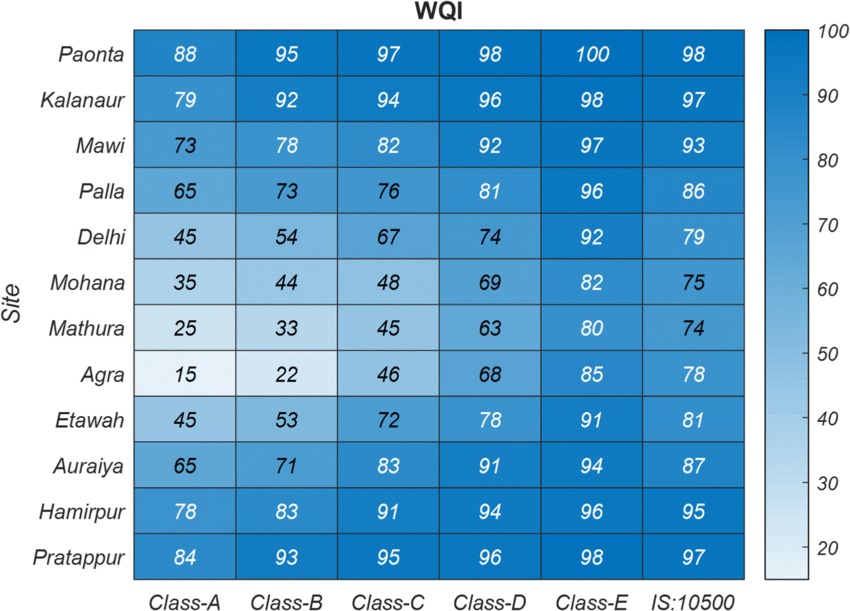

Water Quality Index

The most powerful evidence, however, is not in the data sheets but in the ecosystem. The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) has confirmed more frequent and stable populations of the Gangetic Dolphin, an apex predator that can only thrive in a healthier ecosystem.

Furthermore, the migration of the Hilsa fish, a delicacy that had vanished from upstream areas, has been reported again past Prayagraj. These species are the living, breathing ecological indicators that the top-down mission is delivering tangible results.

3.2 River 2: The Yamuna – The Toughest National Challenge

If the Ganga is the story of a national mission, its largest tributary, the Yamuna, represents the national challenge. The river is critically polluted, most notably in the 22-kilometer stretch through Delhi, which has often been described by experts as “ecologically dead.”

Recognizing this, the government has included the Yamuna’s cleanup under the broader Namami Gange Phase-II. This top-down push is being met by fierce, bottom-up citizen action from groups like the “Earth Warriors” who conduct weekly cleanups, refusing to give up on their river.

The strategy here is one of containment and treatment. Massive new STPs, such as the Okhla plant, one of the largest in Asia, are being constructed to intercept the major drains that currently empty untreated sewage directly into the river.

While the river’s central Delhi stretch remains critical, scientific data provides a crucial insight. Monitoring at Palla, where the river enters Delhi, often shows acceptable DO levels.

The water’s sharp degradation after untreated drains meet it, and its slight recovery after treated water from STPs is released downstream, proves the fundamental concept. The problem is not the river, it is the untreated discharge, and the STPs are the proven solution. The Yamuna’s fight is a demonstration that the technology works, it just needs to be comprehensively applied.

Part 4: The Earth5R Insight – Citizen-Led, Tech-Driven Revival

While top-down missions construct the large-scale infrastructure for river restoration, a second, parallel movement is proving to be the critical catalyst for change. This is the citizen-led, technology-driven approach, a model championed by the environmental enterprise Earth5R.

Their work provides a powerful insight: modern cleanup is not just about waste removal. It is about building a sustainable system based on data, deep community empowerment, and a viable circular economy. This “bottom-up” engine is proving its effectiveness on some of India’s most challenging urban rivers.

4.1 River 3: The Mithi (Mumbai) – The Circular Economy Model

The Mithi River in Mumbai is the quintessential urban waterway. It is not a sprawling, majestic river, but a 17-kilometer channel that winds through dense populations and industrial zones, ultimately serving as a drain for a toxic mix of sewage, effluent, and an overwhelming volume of plastic.

In response, Earth5R, in collaboration with partners like UNTIL (United Nations Technology Innovation Labs) and global packaging company Huhtamäki, initiated the intensive Mithi River Cleanup Project. This is not a sporadic volunteer drive, it is a sustained, professional, and technology-aided operation.

The results, based on their project data, are staggering. Between October 2020 and late 2024, the initiative has reportedly removed over 11,100 tons of total waste from the river system. This figure includes more than 4,440 tons of plastic waste, achieved through a relentless, daily removal rate of approximately 10 tons.

This scale is made possible by integrating modern technology. The project employs solar-powered river cleaning machinery to efficiently collect floating debris. Furthermore, GIS mapping drones are used to identify and track pollution hotspots, transforming the effort from reactive guesswork into a data-driven strategy.

The most crucial “Earth5R Insight” from the Mithi is the “waste-to-value” model. This is the element that makes the cleanup economically sustainable. High-value plastics, like PET bottles, are segregated and sent directly to recyclers.

The real innovation, however, is in handling the low-value, non-recyclable plastics that plague the river. This waste is processed using pyrolysis technology, a method that heats the plastic in the absence of oxygen. This converts it into usable industrial-grade oil and carbon, thus “closing the loop” and ensuring it is a resource, not a pollutant destined for a landfill.

This project’s impact extends deep into the community, creating a behavioral firewall against future pollution. Earth5R reports training over 10,000 local families and 500 businesses in proper waste segregation. This provides green livelihood opportunities for local community members, turning them into stakeholders in the river’s health.

4.2 River 4: The Mula-Mutha (Pune) – The Community Consistency Model

In Pune, the Mula-Mutha rivers face a similar plight. They are choked by domestic sewage and the relentless dumping of solid waste from the city’s rapidly growing population.

Here, the Earth5R model showcases a different but equally powerful virtue: long-term community consistency. Their Mula-Mutha River Cleanup program is a marathon, not a sprint. This sustained effort has been recognized by international bodies, including the UNESCO Green Citizen Program.

This is a story told in weekly actions accumulating over time. For more than six years, consistent, volunteer-driven cleanup drives have successfully removed over 112 tonnes of waste from the riverbanks.

The impact is also quantified in climate terms. By diverting this massive stream of waste from local landfills, where it would have decomposed and released methane, the project has avoided an estimated 150.52 tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions.

This project’s success is rooted in the “ACT” (Awareness, Collaboration, Technology) model. The awareness component is a deep investment in the future, with Earth5R establishing over 200 environmental eco-clubs in Pune schools. This is a long-term strategy to build a new generation of “river guardians.”

The community aspect is also high-tech. Volunteers are trained as citizen scientists. Using a dedicated mobile app, they log, categorize, and geotag the waste they collect. This simple act transforms a cleanup into a real-time data collection project, providing invaluable, granular information for municipal authorities and researchers.

Part 5: The Diverse Fronts – A Nationally Replicated Movement

The successes seen on the Ganga and with the Earth5R model are not isolated incidents. Across India, a diverse range of strategies, from individual determination to large-scale ecological engineering, are proving effective. These efforts show that the cleanup movement is adaptable and is being replicated in various forms.

5.1 River 5: The Godavari – The Youth Power Model

In Rajahmundry, where the Godavari river is revered, the cleanup movement is deeply personal and driven by youth. It demonstrates that significant change does not always require a massive organization.

Initiatives led by local students and youth groups have taken on the task of cleaning the ghats, or steps leading to the river. These groups organize regular drives to clear plastics and ceremonial waste.

This model is less about technology and more about social accountability and inspiring a generational shift in mindset. It proves that consistent, localized action, powered by youth, can maintain the sanctity of a waterway where large-scale machinery cannot, or will not, go.

5.2 River 6: The Sabarmati – The Urban Reimagination Model

The Sabarmati River in Ahmedabad presents one of the most dramatic examples of urban river revival. For years, it was little more than a seasonal, polluted channel that served as a dumping ground for the city’s waste.

The [suspicious link removed] is often cited for its public parks and promenades, but its core environmental success is rooted in engineering. The project’s first and most critical step was to stop the pollution at its source.

This was achieved by constructing a new interceptor sewer system along both banks of the river. This system was designed to catch the raw sewage from 38 major discharge points that previously emptied directly into the riverbed.

By diverting this sewage to treatment plants, the project allowed the river to hold clean water, supplied by the Narmada canal. It is a powerful, albeit debated, case study in how large-scale urban design can be synonymous with river cleanup.

5.3 River 7: The Damodar – The Industrial Accountability Model

Once known as the “Sorrow of Bengal” for its floods, the Damodar River later earned a more notorious reputation as one of India’s most polluted rivers. It flows through a rich coal and industrial belt in Jharkhand and West Bengal, absorbing a heavy load of industrial and mining effluents.

The turnaround for the Damodar is a story of regulatory enforcement and industrial accountability. Sustained pressure from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and state bodies forced polluting industries, especially coal washeries, to comply with new, stricter environmental norms.

A key intervention has been the establishment of Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs). These facilities treat the combined wastewater from clusters of small and medium-sized enterprises that cannot afford their own individual treatment plants.

While challenges remain, water quality monitoring has shown a reduction in the river’s industrial pollutant load, including toxic heavy metals. This proves that a concerted, regulatory push can force an industrial ecosystem to clean up its act.

5.4 River 8: The Adyar – The Ecological Restoration Model

The Adyar River in Chennai, particularly its estuary, was a textbook case of urban degradation. It was a choked, foul-smelling swamp, encroached upon and used as a dumping site for solid waste and untreated sewage.

The solution here was not a simple cleanup but a sophisticated, scientific ecological restoration. The government initiated the Adyar Poonga project, creating what is now known as the Tholkappia Poonga, a 358-acre eco-park.

This was not a landscaping project, it was a habitat revival. The project involved removing 1.5 million cubic meters of silt and domestic debris, planting thousands of native mangrove and terrestrial plant species, and carefully recreating the tidal flow.

The result is a living laboratory of success. The restored park has seen the return of dozens of bird species, fish, and other estuary life. The Adyar model proves that it is possible to not just clean a river, but to scientifically bring its entire ecosystem back to life.

Part 6: The Earth5R Model as a National Blueprint

The restoration of these eight rivers, from the mighty Ganga to the urban Mithi, are not isolated success stories. They are interconnected proofs of concept, revealing a fundamental evolution in India’s approach to its environmental crises.

The evidence shows that the movement is working because it has evolved from a single-engine state-led effort into a powerful dual-engine model.

The national missions provide the essential “hardware,” the large-scale sewage treatment plants and regulatory enforcement. But the citizen-led model, as exemplified by Earth5R’s work, provides the critical “software,” a dynamic, community-owned system that ensures long-term sustainability.

This new approach, which forms a national blueprint for revival, is built on three crucial pillars.

First, this model is data-driven, not guesswork. By leveraging technology like GIS mapping and mobile apps, citizen scientists and project managers can identify the precise sources of pollution, measure the waste collected, and track progress in real-time. This transforms a cleanup from a symbolic gesture into a targeted, scientific intervention.

Second, the model is economically viable by reframing waste as a resource. The old “collect and dump” model was a linear drain on public funds. The new circular economy model, seen in the Mithi River project, actively converts collected plastics into valuable commodities like industrial oil, funding the cleanup and creating sustainable green jobs for local communities.

Finally, and most critically, this blueprint is community-owned. It moves beyond sporadic volunteerism to deep engagement. By establishing environmental eco-clubs in schools and training residents as citizen scientists, this model builds a permanent, local defense network. The community transitions from being part of the problem to being the river’s permanent guardians.

The ultimate proof offered by these eight rivers is not that they are pristine, but that they are undeniably healing. They demonstrate that India’s waterways are not lost causes, but ecosystems that can and will respond to this combination of top-down infrastructure and bottom-up community action.

The blueprint is clear. The dual-engine movement is working. The challenge ahead is one of scale, to take the lessons from these eight successes and apply them to all 351 polluted river stretches identified by the CPCB. The movement is alive, and it is ready to grow.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main argument of this article?

The article argues that India’s river cleanup movement is genuinely working. This success is not due to a single policy but a “dual-engine” approach combining top-down government missions with innovative, bottom-up citizen action, as exemplified by groups like Earth5R.

What is the “dual-engine” movement mentioned?

The “dual-engine” refers to two forces working together. The first engine is the large-scale, government-led infrastructure projects, like the Namami Gange mission. The second engine is the community-led, technology-driven ground action pioneered by organizations like Earth5R.

How is Earth5R’s approach different from traditional cleanups?

Earth5R’s model is not just about removing trash. It is a sustainable system built on a Public-Private-Community Partnership (PPCP). It uses technology for data collection and creates a circular economy, converting waste into valuable resources, which helps fund the project and create green jobs.

How do scientists measure if a river cleanup is “working”?

Scientists measure success using objective chemical and ecological indicators, not just visual appearance. The key chemical metrics are Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), and Fecal Coliform (FC) levels.

What do DO, BOD, and Fecal Coliform (FC) mean?

- DO (Dissolved Oxygen): The amount of oxygen available in the water to support life. Higher is better.

- BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand): The amount of oxygen consumed by bacteria to decompose waste. Lower is better.

- FC (Fecal Coliform): Bacteria indicating contamination from human or animal waste. Lower is better.

What is the most significant ecological proof of a river’s revival?

The most powerful proof is the return of sensitive apex species. The reappearance of the Gangetic Dolphin, Gharials, and fish like the Hilsa in stretches of the Ganga confirms that the entire food chain is healing and the ecosystem is becoming healthier.

Why is the Namami Gange Mission considered a success?

The mission is a UN “World Restoration Flagship” because its integrated approach is working. It has funded hundreds of new Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) to stop pollution at its source and enforced compliance on polluting industries, leading to measurable improvements in water quality and the return of wildlife.

What are STPs and why are they important?

STPs are Sewage Treatment Plants. They are the single most critical piece of infrastructure in the cleanup movement. They intercept and treat raw sewage and industrial effluent from drains before it can be discharged into the river, thus stopping the problem at its source.

What is the “Earth5R Insight”?

The “Earth5R Insight” is that modern restoration must be a sustainable, data-driven, and community-owned loop. It’s not just about cleaning; it’s about creating a circular economy from waste, empowering local communities as “guardians,” and using technology to prove impact.

What is the circular economy model used on the Mithi River?

Instead of just sending waste to a landfill, Earth5R’s project segregates it. High-value plastics are recycled, while low-value, non-recyclable plastics are processed using pyrolysis technology. This converts the plastic waste into usable industrial-grade oil, creating value from pollution.

How much waste was removed from the Mithi River?

The Earth5R project on the Mithi River has been a massive, sustained operation. According to their data, it successfully removed over 11,100 tons of total waste, including over 4,440 tons of plastic, between late 2020 and late 2024.

What technology does Earth5R use in its projects?

Earth5R uses a variety of technologies. These include solar-powered river cleaning machinery, GIS mapping drones to identify pollution hotspots, and a mobile app that allows “citizen scientists” to log, categorize, and geotag the waste they collect.

What is the success story of the Mula-Mutha river cleanup?

The success in Pune is a story of long-term community consistency. Over six years, Earth5R’s weekly volunteer drives have removed over 112 tonnes of waste. More importantly, they have built a “river guardian” movement by establishing over 200 environmental eco-clubs in local schools.

What are “citizen scientists” in the context of these cleanups?

Citizen scientists are local volunteers trained by Earth5R. They use a mobile app to collect and log data about the waste they find. This turns a simple cleanup into a real-time data collection project, providing valuable information on pollution types and sources.

What does the Sabarmati Riverfront project teach us about cleanups?

The Sabarmati project is a prime example of an urban reimagination model. Its core environmental success came from engineering: building an interceptor sewer system that stopped 38 major discharge points from dumping raw sewage directly into the river, allowing the channel to hold clean water.

How was the heavily industrial Damodar River cleaned?

The Damodar’s revival is a model of industrial accountability. It was cleaned through strict regulatory enforcement by the CPCB, which forced polluting industries like coal washeries to comply with environmental norms. A key part of this was building Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs) to treat wastewater from clusters of industries.

What is the Adyar Eco-Park and why is it special?

The Adyar Eco-Park in Chennai is an ecological restoration model. It wasn’t just a cleanup; it was a scientific revival of a 358-acre degraded estuary. By removing silt, planting native mangrove species, and restoring the tidal flow, the project brought the entire ecosystem back to life, evidenced by the return of dozens of bird species.

What are the three pillars of the “national blueprint” for river cleaning?

The article concludes that the successful national blueprint is built on three pillars:

- Data-Driven: Using technology to target, measure, and prove impact.

- Economically Viable: Framing waste as a resource through a circular economy.

- Community-Owned: Engaging citizens, especially youth, as long-term guardians.

What is the scale of the river pollution problem in India?

The problem is enormous. The article cites the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), which has identified 351 critically polluted river stretches across the entire country, making this a systemic, national crisis.

What is the final conclusion of the article?

The final conclusion is that the cleanup movement is verifiably working because it has evolved into a “dual-engine” model. The proof from these eight rivers is not that they are pristine, but that they are healing. The blueprint now exists to scale these successes to all 351 polluted river stretches in India.

Be Part of the Turning Tide

The restoration of India’s rivers is no longer a distant dream, it is a reality in progress, driven by people like you. The success stories of these eight rivers, powered by both national missions and the dedicated citizen action of groups like Earth5R, prove that change is possible.

But for this movement to reach all 351 polluted river stretches, it needs to be a national mission in spirit, not just in name.

You don’t have to be a scientist or engineer to make a difference. Start by practicing waste segregation in your own home. Join a local cleanup drive, or if one doesn’t exist, organize one. Educate your community. Become a “citizen scientist” and report pollution.

The blueprint for a cleaner India exists. Be the movement. Be a river guardian.

~ Authored by Abhijeet Priyadarshi