The Big Question: Yield vs Sustainability

Can organic farming feed the world? The answer depends not just on quantity but on quality,of food, of soil, and of ecosystems. The yield debate has often pitted organic agriculture against conventional farming, with critics arguing that organic yields are 20–25% lower on average. Yet this is only part of the picture. Yield, while crucial, is only one metric of success.

A more holistic question is: can organic farming produce enough while also sustaining the very systems agriculture depends on,soil health, water availability, and climate stability?

In conventional systems, higher yields often come at the cost of environmental degradation. Chemical fertilisers, pesticides, and monocultures have stripped soils of biodiversity and polluted water systems. Organic farming, by contrast, focuses on long-term ecological balance: compost, crop rotation, and polycultures not only grow food but also build resilient agro-ecosystems. That trade-off,yield versus sustainability,is at the heart of the debate.

In regions like Europe, subsidies have allowed organic agriculture to thrive while protecting ecosystems. Meanwhile, in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, smallholder farmers using organic techniques report higher yields than with chemical-intensive methods,mainly because degraded soils respond better to regenerative techniques than to artificial inputs.

The question, then, isn’t whether organic farming can feed the world. It’s whether our global food system can be restructured to support both productivity and sustainability,moving away from a model that values short-term outputs over long-term resilience. As climate change worsens, that shift may no longer be optional. It’s a matter of survival.

Historical Evidence on Organic Productivity

Before synthetic fertilizers and industrial-scale farming, organic methods were the global norm. For thousands of years, civilizations cultivated crops without chemical inputs,relying on compost, manure, crop rotations, and natural pest deterrents. Ancient systems such as China’s “ever-normal granaries,” India’s Vedic farming, and the Incan terraces of the Andes offer compelling evidence that sustainable methods could feed dense populations over long periods. These were not small-scale backyard gardens; they were large, integrated systems that balanced yields with resource regeneration.

One historical standout is the Chinampas system of Mesoamerica, often referred to as “floating gardens.” Built on shallow lakebeds, these platforms used compost and sediment to maintain fertility, producing multiple crop cycles per year. Research by ethno-agronomists suggests that Chinampas were more productive per hectare than many modern farms, while sustaining nutrient cycles and biodiversity.

In India, traditional farming methods prior to the Green Revolution were deeply rooted in seasonal wisdom, intercropping, and natural pest control. Although they lacked the high immediate outputs seen in today’s chemical-based systems, these methods preserved soil fertility and food diversity, critical factors in food security.

It was only in the 20th century, with the advent of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers and chemical pesticides, that the concept of “high productivity” became synonymous with high chemical input. But this shift, while boosting output, introduced long-term problems, depleted soils, groundwater pollution, and fossil fuel dependence.

As modern science reassesses the historical productivity of traditional systems, it’s becoming increasingly clear that organic farming is not a step backward, but a return to resilient, adaptive, and locally attuned agricultural models. What history tells us is simple: sustainability and productivity have coexisted before, under the right ecological and social conditions.

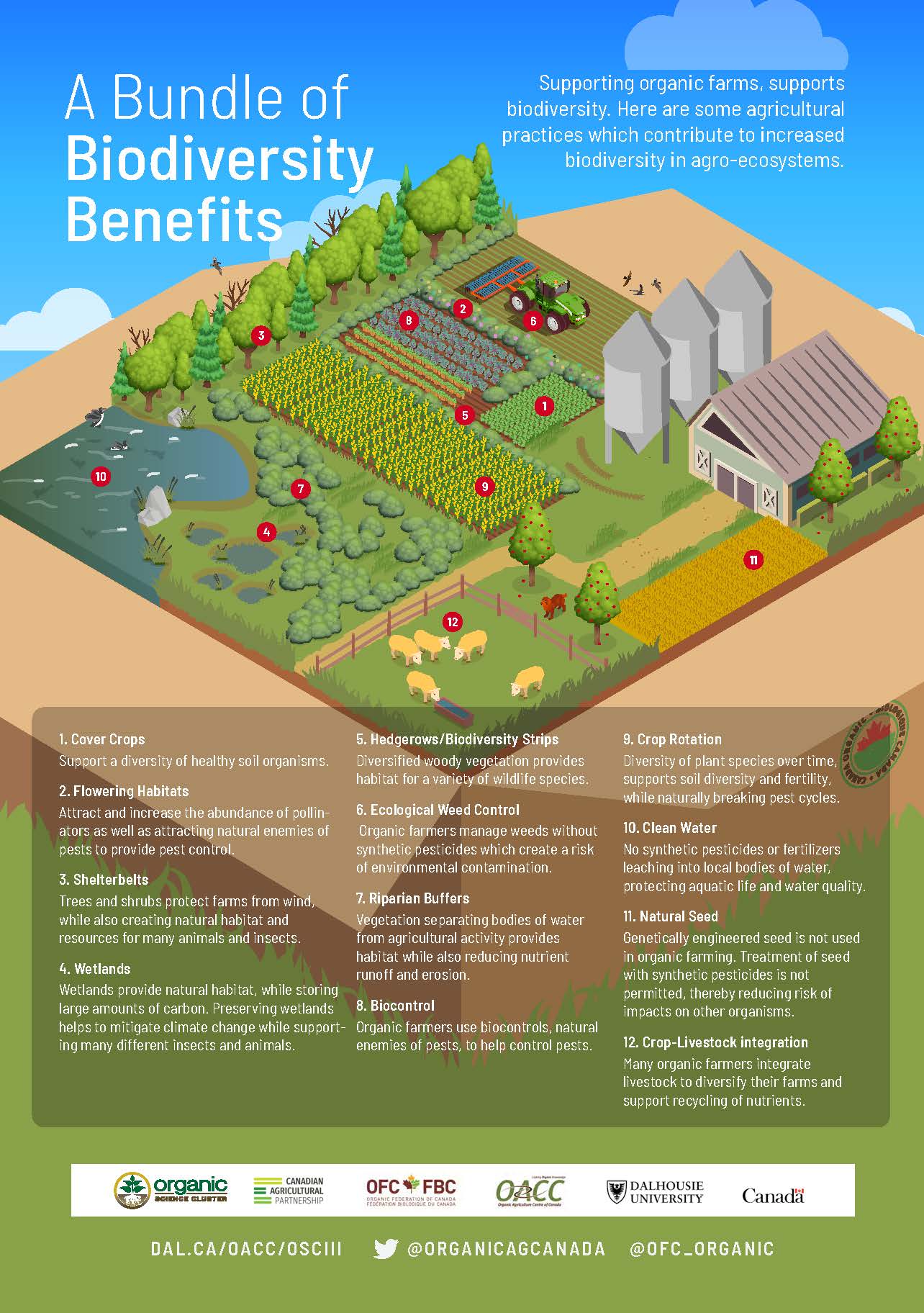

This infographic illustrates how organic farming practices enhance biodiversity, from cover crops and wetlands to biocontrol and crop-livestock integration.It shows that organic agriculture supports ecosystem health while maintaining productive and resilient farms.

Scientific Studies: What They Show (and Miss)

Scientific research on organic farming has produced a complex picture,one that both affirms and challenges popular assumptions. Meta-analyses, such as the landmark 2012 study published in Nature by Seufert, Ramankutty, and Foley, concluded that organic yields are generally 20–25% lower than conventional yields.

However, this gap shrinks dramatically under certain conditions. For example, in leguminous crops (like beans and lentils) and rain-fed systems in developing countries, organic yields are often comparable,or even superior.

But these studies often suffer from a narrow lens. Yield, measured strictly as crop output per acre per year, misses critical dimensions of agricultural success: soil regeneration, biodiversity conservation, and long-term system resilience. Many studies also fail to capture the multifunctionality of organic farms,their ability to provide food, sequester carbon, retain water, and support pollinators, all at once.

A 2016 review in Environmental Research Letters noted that organic systems often outperform conventional ones in terms of energy efficiency, water retention, and resilience to climate extremes. Still, these benefits are rarely factored into traditional productivity metrics.

Even more striking are the findings from long-term trials. The Rodale Institute’s Farming Systems Trial, ongoing since 1981, shows that organic yields catch up with conventional ones after a few years and even outperform them during droughts,thanks to better soil structure and organic matter.

What most scientific studies miss is context. Yields vary not only by technique but by region, crop, infrastructure, and farmer experience. A blanket comparison between “organic” and “conventional” ignores this ecological and social complexity.

Economic Viability for Small and Medium Farmers

For small and medium-scale farmers,who produce over a third of the world’s food,economic viability is the difference between persistence and collapse. Critics often argue that organic farming is too costly or labor-intensive for low-income farmers. But field-level evidence tells a different story: when done right, organic practices can reduce input costs, increase profitability, and build financial resilience over time.

In India, for example, the Andhra Pradesh Community-managed Natural Farming (APCNF) program, covering over 800,000 farmers, has shown that phasing out chemical inputs and adopting organic techniques lowered costs by up to 60%, while maintaining yields and improving net incomes. Farmers rely on local cow dung, composting, and seed banks instead of expensive agrochemicals. The result: a self-sustaining system with minimal dependence on external credit.

The economics of organic farming also shine in premium markets, especially in urban centers where consumers are willing to pay more for certified organic produce. In Kenya and Uganda, smallholder cooperatives engaged in organic coffee and tea exports have reported higher farm-gate prices due to certification and fair-trade agreements. When farmers are organised and supported, organic models become financially empowering.

However, challenges remain. Transition costs,especially in the 2-3 year conversion period,can strain farmers. Access to organic markets is often limited, and certification can be expensive or bureaucratic. That’s where support systems come in: government incentives, NGO training, and cooperatives are crucial for enabling organic transitions.

The Earth5R model offers a compelling example. Through its rural circular economy framework, Earth5R equips villages with waste-to-resource tools, local composting, and community-driven green entrepreneurship. This reduces dependence on external inputs and opens up new income streams from recycling, natural fertilisers, and eco-tourism.

In sum, organic farming isn’t just ecologically sound,it can be economically viable and even transformative for small farmers when paired with the right policies and infrastructure.

Soil Regeneration and Long-Term Productivity

The health of our soils is the hidden engine behind global food production. Yet, conventional farming systems, driven by chemical fertilizers, deep tillage, and monocultures, have caused widespread soil degradation. According to the FAO, over 33% of the world’s soils are moderately to highly degraded due to erosion, nutrient depletion, and loss of organic matter. Without intervention, future yields,regardless of farming system,are at serious risk.

Organic farming offers a path to soil regeneration, not just maintenance. Unlike synthetic inputs that deliver a quick boost but weaken soil biology over time, organic practices like composting, cover cropping, and reduced tillage actively rebuild the soil’s structure, fertility, and microbial life. These methods don’t just preserve productivity,they enhance it over the long term.

The Rodale Institute’s Farming Systems Trial found that organic soils held 15–20% more organic matter than conventional ones, improving water retention and buffering crops against drought. Similarly, research in sub-Saharan Africa has shown that organic manure and legume-based rotations increase soil nitrogen and microbial biomass, directly improving yields over successive seasons.

A healthy soil is also a carbon sink. According to the IPCC, restoring degraded soils through organic farming and agroecology could sequester up to 5 gigatons of CO₂ annually,making it a frontline strategy in climate mitigation.

India’s Earth5R model integrates soil regeneration into its village sustainability approach. By converting organic waste into compost, promoting vermiculture, and training farmers in natural fertiliser production, Earth5R not only reduces landfill pressure but builds the foundation for regenerative agriculture.

In contrast to the input-output mindset of industrial farming, organic systems treat soil as a living, breathing ecosystem. The result isn’t just food today,it’s fertility for generations to come. In the long run, there is no food security without soil security.

The Climate Argument: Methane, Water, and Carbon

Modern agriculture is one of the biggest contributors to climate change, responsible for nearly a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the IPCC. These emissions come from synthetic fertiliser production (nitrous oxide), livestock farming (methane), land use change (carbon dioxide), and energy-intensive machinery. As the climate crisis intensifies, the way we farm has become a central part of the problem,and potentially, part of the solution.

Organic farming reduces emissions at multiple levels. It eliminates synthetic fertilisers, which are responsible for over 1.25 gigatons of CO₂-equivalent emissions annually. Instead, it uses compost, green manure, and crop residues, which not only avoid emissions but enhance soil carbon sequestration. Studies from the FiBL (Research Institute of Organic Agriculture) show that organic fields sequester up to 500 kg more carbon per hectare per year than conventional fields.

Water use is another climate-critical variable. Conventional farming practices often lead to topsoil erosion and runoff, wasting water and depleting aquifers. Organic farms, with their mulching, intercropping, and cover crops, retain water more efficiently and reduce the need for irrigation. A USDA comparison study found organic fields were 20–50% more efficient in water use under drought conditions.

The methane question,especially from livestock,requires nuance. Organic livestock farming is not automatically low-emission, but it typically avoids the industrial-scale concentration of animals that characterizes factory farms. Moreover, when managed in rotational grazing systems, livestock can actually enhance soil carbon storage, making emissions part of a balanced ecological cycle.

Earth5R’s rural circular economy model plays a unique role here. By promoting biogas from organic waste, community composting, and low-emission transport, it closes the loop on emissions, turning waste into energy and soil enrichment.

In short, climate-resilient agriculture must move away from fossil-fueled intensification. Organic farming, integrated with local circular models, provides a realistic and regenerative path forward for climate mitigation and adaptation.

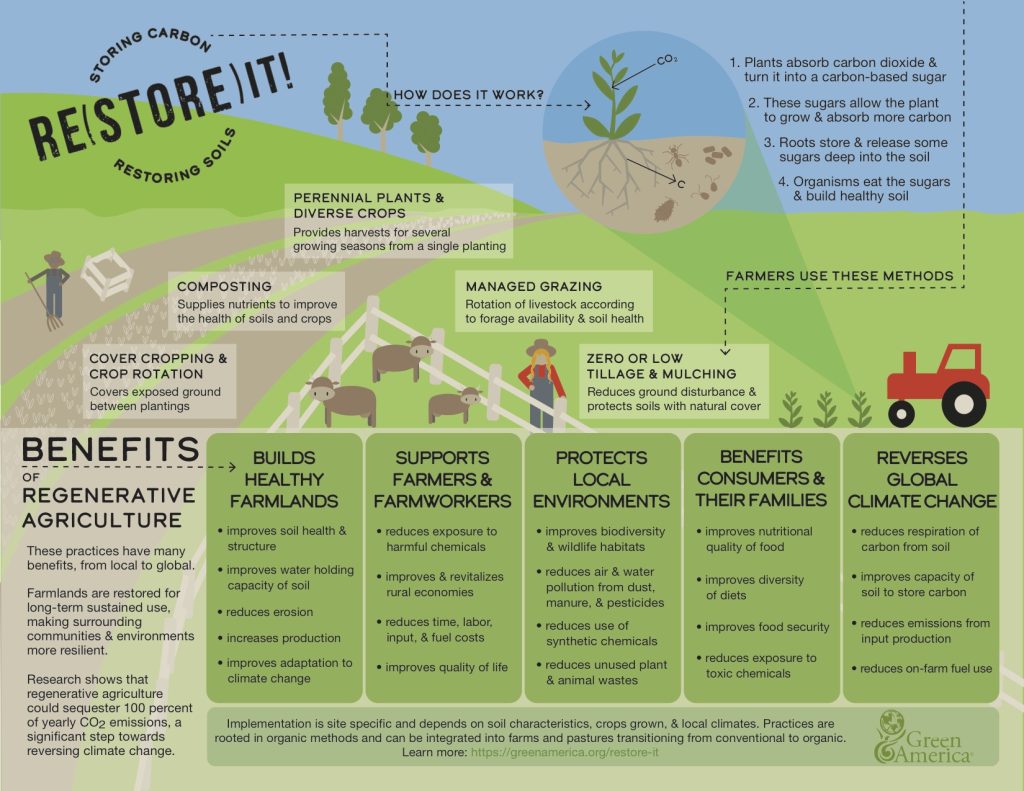

This infographic explains how regenerative agriculture restores soils, stores carbon, and builds resilient farmlands using practices like composting, crop rotation, and managed grazing. It highlights that such methods not only boost yields and farmer livelihoods but also contribute to reversing global climate change.

Food Security in Developing Nations

The global debate on organic farming often centers around the industrial North,but the real test lies in the Global South, where food insecurity is most acute. Over 828 million people go hungry worldwide, with a significant majority living in developing nations. These regions face complex challenges: land degradation, climate shocks, lack of infrastructure, and rural poverty.

Conventional farming methods, introduced through Green Revolution programs, did boost grain yields. But they also left behind a trail of problems: salinized soils, groundwater depletion, and farmer debt cycles. In contrast, organic and agroecological practices offer a lower-cost, ecologically sustainable alternative,especially for smallholder farmers who lack access to chemical inputs.

A 2021 meta-study by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) found that agroecology can increase both yields and incomes in marginal regions, while enhancing food sovereignty. In Tanzania, organic vegetable farming supported by local cooperatives has helped women farmers double their income while improving household nutrition. In India, the Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) initiative across Andhra Pradesh aims to scale chemical-free agriculture to six million farmers, proving that food security doesn’t have to rely on industrial inputs.

The Earth5R green village model builds food security through community composting, rooftop farming, skill development, and plastic-to-resource conversion. By empowering rural communities to grow food sustainably and manage waste effectively, Earth5R tackles food insecurity at its root,ecological, social, and economic vulnerability.

Ultimately, food security in the Global South is not just about calories, but about building resilient, sovereign systems that can withstand climate shocks, market volatility, and input scarcity. Organic farming, combined with local empowerment models, is a crucial tool in that fight.

Consumer Behavior and Demand Forecasts

Consumer demand is the engine that shapes global agricultural markets,and when it comes to organic food, that engine is accelerating fast. According to the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) and IFOAM’s 2024 report, the global organic food market surpassed $150 billion USD, with annual growth rates of 8–10% in key markets like the U.S., EU, and China. But beyond the numbers lies a deeper shift in public consciousness: people are choosing food not just for nutrition, but for its impact on health, climate, and ethics.

Organic consumers, especially in urban and middle-income populations, are increasingly concerned about pesticide residues, soil degradation, animal welfare, and carbon footprints. In India, demand for organic produce in cities like Bengaluru, Mumbai, and Delhi has led to a booming sector of organic delivery startups, farmers’ markets, and farm-to-fork supply chains. Likewise, across Africa and Latin America, youth-led eco-entrepreneurship is tapping into growing domestic markets for clean, locally sourced food.

However, the demand landscape is uneven. While some regions experience booming organic sales, others struggle with affordability and awareness gaps. In many developing nations, organic produce is often perceived as elitist or niche. Bridging this divide requires policy support: subsidies, awareness campaigns, and institutional procurement (like schools and hospitals buying organic) can create mainstream visibility and reduce price gaps.

Forecasts suggest that by 2030, the global organic food market could double if price parity and trust in certification improve. Consumers are ready,but systems must adapt.

Earth5R leverages this shift in demand through its citizen engagement model, training households and youth in urban composting, zero-waste living, and conscious consumption. By creating both supply and demand within local ecosystems, Earth5R closes the loop,aligning personal health with planetary sustainability.

In short, consumer behavior is no longer passive. It’s a form of activism and investment,and it’s reshaping the future of farming, one purchase at a time.

Role of Governments, Donors, and Markets

Organic farming may be rooted in the soil, but its future is shaped just as much by policy, funding, and market structures. Governments, international donors, and financial institutions hold immense power to scale or stall the organic movement,not through production alone, but through the systems that support it.

Historically, most agricultural subsidies have favoured industrial farming. The OECD estimates that over $500 billion USD is spent annually on agricultural support worldwide, the vast majority of which goes to conventional inputs like synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, and fossil fuel subsidies. Redirecting even a fraction of this toward organic transitions, training, and market access could fundamentally shift the global food system.

Examples of positive intervention are already emerging. In Bhutan, the government’s bold vision to become 100% organic has transformed agriculture into a pillar of national identity and environmental strategy. In the European Union, the Farm to Fork Strategy aims to make 25% of all farmland organic by 2030, backed by incentives, research funding, and certification support. Meanwhile, India’s Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) has supported over two million organic farmers, offering training, market linkages, and group certification.

Donors also play a key role. Organizations like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, IFAD, and GIZ are funding agroecology pilots across Africa and Asia. But critics argue that more emphasis is still placed on biotech and input-intensive models. Systemic support for organic, community-led models remains underfunded and under prioritized.

Earth5R provides an example of how market-based solutions can be community-driven. Its model transforms rural and urban spaces through micro-entrepreneurship, waste recovery, organic composting, and environmental education. By turning sustainability into a viable livelihood, it bridges grassroots action with macroeconomic goals.

In essence, the shift to organic won’t happen through individual effort alone. It requires a realignment of policies, public spending, and market logic. When governments and donors step in with vision and support, organic farming becomes not just possible,but powerful.

Bridging the Gap: Scaling Without Compromise

Scaling organic farming from niche practice to global solution is not just a matter of expanding acreage,it’s about transforming systems without losing integrity. The fear that organic agriculture cannot “scale up” to meet global demand is based on a false binary: that growth must come at the cost of values. In truth, scaling without compromise means evolving smarter, not bigger.

One critical shift is moving from the industrial idea of “scaling up” to “scaling out”,replicating locally adapted, community-led models rather than imposing uniform practices. This is where the concept of distributed sustainability becomes key: many small, resilient systems working in harmony with their ecosystems. It’s not romanticism,it’s resilience. And it’s already happening.

The Earth5R rural circular economy model is a prime example. Instead of top-down interventions, it empowers village communities to build self-sufficient ecosystems. By training locals in waste management, soil regeneration, organic farming, and green entrepreneurship, Earth5R shows how impact can grow horizontally, through replication and knowledge sharing,not centralisation. These scalable, human-sized models offer real alternatives to industrial expansion.

Technology also plays a role, but not in the form of gene editing or chemical intensification. Instead, digital farmer cooperatives, mobile soil testing kits, blockchain for organic traceability, and AI-driven crop planning tools offer precision, transparency, and trust,without compromising organic principles.

The challenge is to scale agroecology while preserving diversity,of crops, of methods, and of communities. Certification processes must become more accessible, training more widespread, and value chains more inclusive. Governments and private players must invest in infrastructure that supports smallholders,not marginalises them.

If done right, scaling organic farming could feed the world,not just with calories, but with sustainability, dignity, and hope. The goal isn’t just more food. It’s better food, from better systems, for a better future.

Conclusion: Rethinking Abundance for a Finite Planet

The question “Can organic farming feed the world?” is not just agricultural,it’s philosophical. It forces us to confront the limits of extractive systems and the illusion that more chemicals, more machines, and more monocultures can solve problems they helped create. The evidence is clear: organic farming can produce sufficient, nutritious food,especially when paired with community-led models, technological support, and policy alignment.

What makes organic farming uniquely powerful isn’t just what it avoids,pesticides, GMOs, synthetic inputs,but what it regenerates: soil, water, biodiversity, livelihoods, and hope. This isn’t about going backward; it’s about moving forward with wisdom,drawing from science, tradition, and ecology in equal measure.

The challenge now is scale. But not the scale of industrial sprawl,instead, a network of sustainable systems, each tailored to its landscape, culture, and community. Organizations like Earth5R show that with vision, training, and local leadership, these systems can thrive and multiply,turning waste into wealth and farms into ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions: Can Organic Farming Feed the World? A Deep Dive into Yields, Economics, and Climate Impact

Is organic farming truly capable of feeding 8–10 billion people?

Yes, if integrated with agroecological principles, food waste reduction, and equitable distribution. Studies show that organic systems can match or exceed yields in rain-fed and low-input areas, especially in the Global South.

Why are organic yields often lower than conventional yields?

They can be, especially in the short term. However, over time, organic yields stabilize and even outperform conventional ones during droughts or soil-depleted conditions due to improved soil health.

Is organic food more nutritious?

Many studies indicate higher antioxidant levels, lower pesticide residues, and better omega-3 profiles in organic produce and meat. However, nutritional differences can vary by crop and farming method.

Does organic farming really help combat climate change?

Absolutely. Organic systems reduce greenhouse gas emissions, sequester carbon, and improve water efficiency, making them a key climate mitigation strategy.

Is organic farming economically viable for small farmers?

Yes, especially when farmers reduce chemical input costs, access premium markets, or join community-supported models like those run by Earth5R.

What is the role of compost in organic farming?

Compost is the backbone of organic soil fertility. It improves structure, nutrient availability, and microbial activity, reducing dependency on synthetic inputs.

Can organic farming work without animal manure?

Yes. Techniques like green manures, cover crops, composted plant material, and biofertilizers can meet nutrient needs in plant-based systems.

Is organic certification accessible to smallholders?

Currently, it’s a challenge due to costs and bureaucracy. However, participatory guarantee systems (PGS) and group certifications are making progress.

Are organic farms less productive in developing nations?

Not necessarily. In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa or India, organic methods often outperform conventional ones due to degraded soils responding better to regenerative inputs.

What’s the difference between organic and regenerative agriculture?

All organic is regenerative in spirit, but not all regenerative is certified organic. Regenerative farming may use holistic practices beyond organic standards, such as integrated livestock, no-till, and indigenous knowledge.

Does organic farming use pesticides?

Yes, but only natural or minimally processed substances, such as neem oil or copper sulfate, and only when absolutely necessary.

How does Earth5R promote organic farming?

Earth5R supports villages through waste-to-resource training, compost production, circular economies, and community-led natural farming, creating local green jobs and sustainable food systems.

Why is soil health so critical in organic farming?

Healthy soils hold water, resist erosion, store carbon, and feed plants. Organic farming views soil as a living ecosystem, not a mere growing medium.

Is organic farming scalable in urban areas?

Yes,through rooftop gardens, vertical farming, and composting initiatives, as promoted by Earth5R’s urban sustainability programs.

Does organic farming require more land?

Possibly, in some cases. However, reducing meat consumption, food waste, and biofuel crops can free up enough land to support organic transitions without expansion.

Can technology help scale organic farming?

Yes. Tools like satellite soil monitoring, mobile-based farm advice, blockchain traceability, and AI planning are helping small organic farmers scale effectively.

Is organic food always more expensive?

Often, yes,but prices drop when supply chains shorten, certification costs fall, and consumer demand increases. Policies also help reduce cost barriers.

What are examples of countries supporting organic farming at scale?

Bhutan, Austria, Germany, and India have robust organic programs. The EU aims for 25% organic farmland by 2030 under the Farm to Fork Strategy.

Can organic farming create rural jobs?

Yes. It’s more labour-intensive, but in a good way,it creates green employment in farming, composting, training, and processing.

How can individuals support organic farming?

Buy organic, compost at home, reduce food waste, support local farmers, and engage with organisations like Earth5R to amplify impact.

Take Action for a Regenerative Food Future

To truly build a food system that nourishes both people and the planet, collective action is essential. Policymakers must redirect subsidies and policies to support regenerative and organic farming practices. Consumers should choose organic not merely as a product preference but as a commitment to environmental health. For farmers, sustainability is not a sacrifice but a safeguard for their land and livelihoods. Students and activists can play a crucial role by educating themselves, volunteering, and amplifying solutions like those pioneered by Earth5R. Feeding the world sustainably is possible, but it requires us to transform not just how we farm, but why we farm.

– Authored by Sohila Gill