Defining the Two Models: Clarity in Concepts

When discussing the future of food systems, it’s crucial to begin with precise definitions of what we mean by sustainable agriculture and organic farming. Though they share common aspirations, these approaches differ fundamentally in scope, method, and underlying philosophy.

Sustainable agriculture is best understood as a holistic framework combining environmental resilience, economic viability, and social responsibility. It encompasses practices such as drip irrigation, integrated pest management, agroforestry, and crop diversification. The core aim is to maintain productivity while preserving natural resources, enhancing soil health, conserving water, and supporting farm communities over the long term.

A compelling case comes from Earth5R’s Sustainable Agriculture Program, implemented across rural India. Over one year, 300 volunteers engaged with roughly 108,000 farmers, covering topics from organic pest controls and water management to financial literacy and renewable energy use. Farmers who adopted drip irrigation reported water savings of 20–30%, and over half a million liters were conserved monthly across the program.

In contrast, organic farming is a more narrowly defined system grounded in strict input standards, eschewing synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, GMOs, antibiotics, and growth hormones in favor of composts, manure, crop rotation, and natural biocontrol methods. According to global data, around 70 million hectares were organically managed as of 2019, with half located in Australia.

While sustainable agriculture is outcome‑oriented—focusing on resource efficiency and community welfare—organic farming is process‑driven, concerned first with adherence to strict rules on what can be used in the field.

An illuminating analogy: organic farming is akin to hand‑crafting a product using certified natural ingredients, whereas sustainable agriculture is like designing a factory system that minimizes waste, optimizes energy use, and empowers workers, regardless of whether its inputs are wholly natural.

Importantly, the boundaries between the two are not rigid. Organic farming can be one valid method within a sustainable system, offering benefits such as enhanced biodiversity and ambient ecosystem health. But a sustainable system may also integrate precision‑agri methods, cover cropping, or even low‑toxicity controlled inputs that are not officially “organic” but deliver environmental gains.

This distinction matters enormously when making policy decisions, crafting farmer support programs, or educating consumers. For instance, Earth5R’s regenerative-focused sustainable programs emphasize effective soil replenishment with composting kitchen waste, agroforestry, and monitoring tools, leading not only to healthier soil but also to higher farmer incomes. In Karjat, Maharashtra, 150 households shifted to low‑input farming, boosting soil carbon and increasing household income by 20%.

Thus, while both agriculture models aim for healthier, fairer, and greener food systems, organic farming is primarily about clean inputs, and sustainable agriculture is about effective systems. Keeping this distinction in focus sets a strong foundation for evaluating how these paths diverge and overlap—and why it matters for agriculture’s future.

Overlap and Divergence Between Organic and Sustainable

In the evolving landscape of modern agriculture, sustainable and organic practices increasingly intersect—yet they remain distinct pathways with different priorities. Understanding both their common ground and key differences is essential for anyone studying the future of food systems.

At their core, both organic and sustainable agriculture strive to reduce chemical inputs, regenerate soils, preserve biodiversity, and support farmer welfare. But this shared ambition masks important contrasts. Organic farming is built upon a strict rulebook—no synthetic fertilizers, no GMOs, and no chemical pesticides—while sustainable agriculture adopts a problem-solving mindset, choosing whichever methods achieve low environmental impact and community resilience, whether those are organic, regenerative, or technologically enhanced.

Consider Earth5R’s integrated model in Maharashtra, where farmers simultaneously use composting (an organic staple), drip irrigation (a water-saving measure often outside organic rules), and agroforestry systems. This hybrid technique consistently improved soil carbon by 15% in a year, while also boosting incomes, showing how the rigidity of organic protocols can blend with the flexibility of sustainable strategies.

A telling analogy: picture organic farming as a coach focused solely on playing by the rulebook, while sustainable agriculture is the strategist who adapts—using analytics, rotation plans, and precision tools—to win the game. Both aim to score, but the ballpark is different.

From a scientific standpoint, research reveals noteworthy overlaps and pitfalls. A comprehensive meta-analysis spanning nearly 3,000 studies found that organic farms deliver 30% higher biodiversity and significantly better soil organic matter, but also display 15% lower yield stability compared to conventional systems.

Sustainable systems, by contrast, often embrace practices from both worlds—such as minimal tillage and cover cropping—providing yield reliability akin to conventional output, while rebuilding ecosystem services over time.

Earth5R’s “Organic & Sustainable Agriculture Program” reflects these nuances. Tailored to local conditions, the initiative applies organic composting, microbial inoculants, and seed preservation (organic strengths), combined with digital crop monitoring, drip irrigation, and farmer-producer groups (sustainable strengths). This dual strategy elevates yields, environmental health, and farmer earnings—without forcing compliance to one agricultural ideology.

Yet divergence remains. Organic certification offers a clear, consumer-friendly label—trustworthy, but also restrictive and often costly. Sustainable agriculture, lacking such uniform standards, can feel ambiguous. As one Indian farmer in Earth5R’s CircularFarms network put it, “Turning organic was easy to explain, but telling consumers we’re sustainable… It’s harder to show.”

Furthermore, policy support tends to differ. Organic farms benefit from premium prices and niche buyer channels, but they struggle with land-use constraints and certification costs. Sustainable farms gain flexibility but are often overlooked in conventional subsidy schemes that favour singular models.

Environmental Footprint Comparison

As the world grapples with climate change, land degradation, and resource scarcity, scrutiny of environmental footprints—greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, land occupation, and energy consumption—has become indispensable in evaluating agricultural models. Both organic farming and sustainable agriculture appeal to environmental goals, but the science reveals a dynamic tension between area-based and product-based impact metrics.

Organic systems deliver clear advantages per hectare. Multiple life-cycle assessments (LCAs) from Europe and North America show that, when measured per unit of land, organic farms emit fewer greenhouse gases, leach less nitrogen, and build richer soil organic matter. One review of 77 comparative studies concluded organic cropping reduced climate-changing emissions, ecotoxicity, and acidification ≈ independent of yield metrics. Similarly, a decade-long analysis across 40 farms reported carbon emissions from organic systems were 48 % lower, while soil carbon sequestration rose 20–40 %.

Yet context and scale transform the narrative. Though organic farms sequester more carbon in soil and emit less per hectare, they typically produce 10–30 % less food per plot. To compensate, wider acreage—and often land conversion—is needed. One meta-analysis warned that 84 % more land may be necessary under organic farming to meet equivalent yields. This expansion erodes environmental benefits, potentially triggering deforestation and habitat loss.

The story complicates further when centering on functional units like kg of produce. A comprehensive European meta‑analysis of 46 systems found organic production required up to 110 % more land per kg, and led to 37 % higher eutrophication, though energy use fell by 15 % (iopscience.iop.org). Notably, the same study found no significant difference in greenhouse gas emissions per kg—a reminder that footprint advantages aren’t always maintained without careful scaling strategies.

But nuance emerges across crops and regions. A cradle-to-farm gate study in Egypt compared organic versus conventional cotton and found nearly equal yields (3,364 kg vs. 3,400 kg per hectare), while energy efficiency and environmental impact strongly favored organic cultivation. And in Sweden, organic peas, when lifecycled, actually produced 50 % higher climate impact than their conventional counterparts, because of land pressure.

These disparities highlight an important reality: impact metrics depend deeply on context—crop type, yield gaps, and regional conditions. To illuminate how this translates on the ground, one can look at Earth5R’s pilot program in Maharashtra. There, farmers combined compost, drip irrigation, and multi-cropping in a system that balanced input savings with stabilized output, delivering enhanced environmental benefits without the yield losses seen in pure organic systems.

An illustrative analogy frames this well: organic farming is like owning an electric car—you produce zero tailpipe emissions, but if the grid runs on coal, your overall carbon benefit may erode. Sustainable agriculture, in contrast, is like applying smart grid charging, adjusting not just emissions (inputs) but also optimizing when and how energy is used.

A recent meta-analysis of 50 years of diversified farm systems, including organic rotations, agroforestry, and soil inoculation, showed ecosystem services and carbon sequestration rose to 2,000 % over several decades, without sacrificing yield.

This suggests that attentive, integrated practices deliver better environmental returns over time than rigid input restrictions alone.

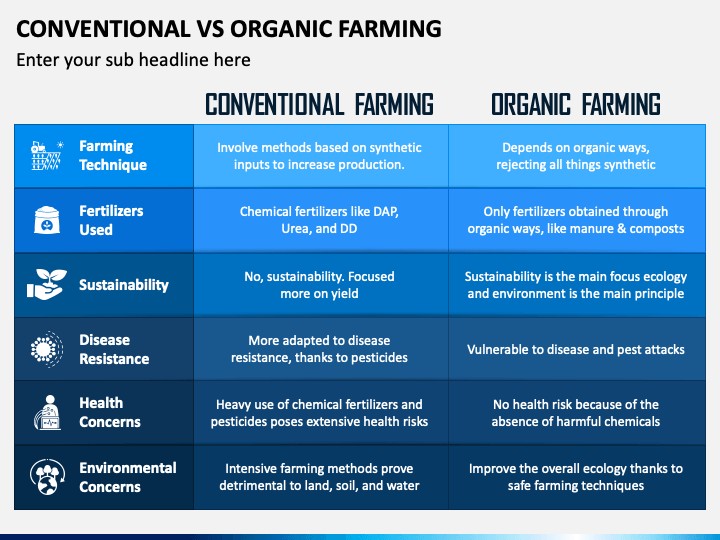

The infographic below compares conventional and organic farming techniques, highlighting their impact on health, sustainability, and the environment. Understanding these differences is crucial as we rethink food systems for a more sustainable future.

Inputs, Water, Soil, and Carbon Impact: A Closer Look

In the intricate world of agriculture, the measures we take can have profound consequences—turning a seemingly harmless irrigation method into a potential climate threat, or transforming soil into a carbon sink. The comparison between organic farming and sustainable agriculture must delve deep into these mechanics, evaluating not just what’s used, but how land, water, and energy are managed.

Inputs tell a compelling story. Organic farms are governed by strict prohibitions—synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, GMOs, and growth regulators are off-limits. Instead, these systems rely on compost, green manures, biological pest controls, and crop rotations.

A seminal study on rice cultivation found that when organic methods were adopted, alternate wetting and drying (AWD), a water-saving method, the system slashed methane emissions by up to 85% and simultaneously reduced toxic metals in grains, all without compromising yield. That’s a powerful demonstration of how carefully designed organic inputs can yield environmental payoffs.

Yet organic systems also bring water and land implications. Since synthetic nutrients are typically more concentrated, organic substitutes often require larger volumes and additional labour to achieve nutrient parity, possibly increasing water use during irrigation. Meanwhile, slower nutrient mineralisation can demand more land to produce equivalent yield, raising carbon release concerns if new land is ploughed (FAO report).

Sustainable agriculture, meanwhile, emphasises optimisation. Techniques like drip irrigation, laser-levelled rows, and underground piping can reduce water use dramatically, as seen in intensive farms in East Anglia’s Fens region, where subterranean irrigation preserved peatlands and cut carbon emissions by nearly 50%.

Earth5R’s model in rural India employed drip systems alongside organic mulching and microbial inoculants, trimming water use by 20–30% while boosting soil organic content across dozens of villages. By combining smart inputs and modern tech, sustainable agriculture can tailor resource applications perfectly to soil and crop needs.

When it comes to soil health and carbon dynamics, the differences are even more nuanced. Organic farming excels at elevating soil organic matter, enriching microbial life, and enhancing structure—a consistent finding across dozens of global studies. However, the payoff may arrive slowly, and organic systems can struggle to match nitrogen availability seen in conventional analogues, which slows early season growth.

Sustainable agriculture approaches this problem from multiple angles: integrating cover cropping, reduced tillage, compost application, and AI-powered soil carbon monitoring—such as the spectral probe technologies used by Perennial and Downforce—to both optimise soil health and enable verifiable carbon storage gains.

A fitting analogy is to compare farming to banking. Organic methods are like regular, safe deposits, steadily increasing soil richness over time. Sustainable systems, in contrast, balance long-term “deposits” with smart “investments”, using technology to measure current soil reserves and strategic withdrawals via precision inputs.

Earth5R’s multifaceted work in Maharashtra offers a tangible case. Farmers there combine organic composting with drip irrigation, microbial inoculations, and soil carbon assessments. Within a year, many saw 20–40% gains in topsoil organic carbon, while water-use efficiency drastically improved, without expanding acreage.

Ultimately, organic farming ensures clean inputs and richer soil, but may sacrifice precision or efficiency. Sustainable agriculture achieves nuanced optimisation—marrying organic principles with engineering and digital tools. The future lies not in choosing between them, but in merging their strengths: clean inputs, tailored systems, and data-driven stewardship to conserve water, soil, and the climate.

Which Model Supports Small Farmers Better?

In countless villages across the developing world, small farmers stand on the frontlines of agricultural transitions—balancing tradition, ecology, and profit. But when the question arises—does organic farming or sustainable agriculture better serve their interests?—the evidence reveals nuanced realities rooted in science, structure, and scale.

For many smallholders, the lower input costs of organic farming are a lifeline. In a pioneering 2010 study covering Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, researchers found that organic systems reduced production costs without compromising net margins, with intercropped staples offsetting minor yield losses in rice and wheat. This echoes findings from Morocco, where peri-urban organic farms achieved higher agri-environmental scores, even outperforming conventional farms in economic viability through reduced dependency on chemical inputs.

But the prize doesn’t stop there. Global meta-analyses reveal that organic farming is 22–35% more profitable than conventional systems, largely thanks to premium prices. Take Uttar Pradesh, for instance, where small farmer producer organizations like Madhoganj FPO sell organic millets under local brands, leveraging Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) to capture higher market returns and build community trust.

Still, context matters. In a hazelnut study from Turkey, organic yields diverged by region: in one area they were 12% higher, in another 1% lower—yet premiums boosted net margins by up to 117% where yields were maintained. Similarly, in Assam’s tea plantations, organic smallholders earned more over a decade, provided yield variances were managed effectively.

On the other side, sustainable agriculture offers broader resource resilience. Earth5R’s pilot in Maharashtra combined drip irrigation, organic compost, and microbial inoculants, helping 150 households increase topsoil organic content by 20–40%, stabilise yields, and raise incomes by 20%. By integrating smart technologies and regenerative principles, sustainable approaches soften the yield volatility inherent in pure organic systems.

A powerful analogy emerges: organic farming equips farmers with a dependable, basic toolkit—compost, no synthetic sprays, biodiversity—while sustainable systems supply a full workshop, with digital sensors, precision irrigation, and climate-smart buffers that can respond dynamically to droughts, pests, and market shifts.

Yet the path ahead isn’t free of complexity. Larger organic operations increasingly mimic conventional farms, relying on permitted synthetic substitutes and mechanised systems rather than agroecological practices, thereby eroding the ideals and benefits originally tied to smallholder organic farming, as highlighted by Cornell University’s research. In contrast, sustainable agriculture—though unfettered by rigid certification—often lacks coherent schemes to help smallholders access technology or reach premium markets.

So, which model supports small farmers better? The answer lies in context and integration. Where land is small and labour relatively abundant, organic systems can shine, especially when underpinned by community-led PGS schemes that reduce certification costs and boost market access. Meanwhile, in regions facing resource uncertainty, scale, or climate variability, blended sustainable systems—which include organic inputs alongside technology and community structures—can buffer risk and enhance resilience.

Ultimately, for small-scale producers, the ideal strategy may be a custom hybrid—organic principles augmented by sustainable tools, supported by local institutions, and tied to direct-market or premium distribution channels. Initiatives like Earth5R’s CircularFarms network in Maharashtra offer a blueprint: equitable, locally-driven, and scientifically grounded models where smallholders regain autonomy, increase incomes, and steward soil and water systems alike.

Market Access, Certification, and Consumer Confusion

The marketplace is a battleground of competing labels, claims, and certifications—where organic and sustainable branding intersect, often resulting in consumer bewilderment and uneven access for farmers. Understanding how each model is certified, marketed, and perceived is vital for shaping trust in the future of food.

Organic farming benefits from well‑established certification systems. In regions such as the United States, European Union, Canada, and Japan, the term “organic” is governed by legally enforceable standards, overseen by government agencies and independent certifiers. These standards outlaw synthetic fertilizers and GMOs, regulate animal welfare, and require detailed audit trails and inspections. The result? Consumers tend to trust the label, pay price premiums of 4 – 116%, and assume health and environmental benefits.

Yet the system isn’t flawless. In Australia, for instance, large-scale producers have occasionally exploited loopholes—labeling cosmetic ‘organic’ goods without certification, misleading consumers, and undermining genuine producers. A report in Meat + Poultry revealed that even in the US, misunderstanding runs deep: 74% trust USDA organic, yet many don’t realize its standards already encompass pesticide and GMO bans.

Contrast this with sustainable agriculture, which lacks a single global certification. Programs like Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, GlobalG.A.P., and Earth5R’s verification platform offer diverse seals. Yet each reflects different priorities—ecosystem conservation, fair wages, digital traceability—making the label landscape confusing and fragmentary.

Studies show ambiguous claims resonate positively with consumers—ecolabels generally boost purchases. But the catch is trust; when standards are unclear or poorly enforced, skepticism can erase brand loyalty. As one viticulture insider noted, organic regulation is systematic but static, while sustainable labels are “more holistic—but certainly much more comprehensive,” and yet lack transparency.

For farmers, certification is a double-edged sword. Organic requires costly compliance, often involving three years of chemical-free land, paperwork, regular audits, and fees, costs that can deter smallholders. Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) have emerged as a local, community-based alternative, reducing cost and complexity while reinforcing trust in domestic and regional markets. Yet, without legal backing, PGS may not unlock export premiums or international shelves.

Sustainable certification, on the other hand, tends to be more modular and flexible, suiting low-income or small-scale producers. Earth5R’s digital platform lets farmers log practices via smartphone or assisted entry, earning “Green Points” and unlocking carbon credits—all without organic-level bureaucracy. However, some exporters and supply chains still prioritize the organic flag, leaving otherwise sustainable farms marginalized if they lack that seal.

An apt analogy: think of organic certification as a master’s degree—costly and structured but widely recognized. Sustainable certifications are specialist diplomas—modular, cheaper, and context-specific, but less universally understood. Certification is less about proving ecological integrity than securing market trust and access.

Policymakers are starting to respond. Australia’s push for domestic organic certification aims to close loopholes and reassure consumers, while the EU has launched reforms to reinforce clarity on “organic plus” attributes, such as local, ethical, or nutritional enhancements. In parallel, McKinsey‑Nielsen research suggests that 67% of consumers want default sustainability, yet 48% say they struggle to identify what that means.

Long‑Term Cost vs Benefit for Farmers and Buyers

As agriculture evolves under the twin pressures of climate change and resource scarcity, the economics of farming have never been more scrutinised. When weighing organic against sustainable agriculture, the long-term financial narrative is intricate: one defined by upfront investments, evolving market dynamics, and shifting ecosystem services.

Sustainable agriculture often requires hefty upfront costs. Adopting cover crops, precision irrigation, no-till equipment, or integrated pest management can initially dent farmers’ pockets. According to a recent Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) review, the first-year cost of implementing reduced tillage and cover crops across the EU could reach €6.9–16.7 billion, mainly in machinery and restructuring of farm operations.

But after transition, operational savings—fuel, fertilisers, chemicals—often offset costs, producing economies that conventional systems struggle to match. The IEEP found that although farm income may dip during the transition, profitability post-integration can equal or exceed conventional yields, especially in resilience to market shocks and extreme weather.

By contrast, organic farming’s economics hinge on input reduction and premium prices. Avoiding synthetic fertilisers and pesticides lowers material costs, and organic commodities often sell for 22–38% higher prices globally, according to market analyses. One long-term study at Iowa State University’s Neely-Kinyon LTAR found that organic grain rotations earned significantly more for corn and soybean—$51–95 extra per acre—due to lower input expenses.

Likewise, research from Munich Technical University revealed that conventional farming could cost up to €800 more per hectare than organic when externalities like emissions are factored in.

The benefits, however, come with caveats. Certification and opportunity costs loom over organic systems. Farms typically undergo a three-year transition during which yields may dip without the ability to fetch premiums.

Certification itself comes with audit fees and compliance burdens. Sustainable models—especially those like Earth5R’s that integrate technology with regenerative methods—have started to defray these challenges. Their mobile platform facilitates tracking sustainable practices and unlocking digital “Green Points” or carbon credits, helping farmers monetise ecological stewardship even without going organic.

Earth5R’s case studies across India show farmers saving approximately INR 10,000 per year on chemical inputs, increasing yields by 15–20% through drip irrigation and compost, and further monetising agricultural waste via fuel pellets, collectively generating INR 12 million. These dual benefits—cost reduction and new revenue streams—highlight how sustainable systems can outperform both conventional and organic setups, without sacrificing flexibility or incurring rigid certification costs.

For consumers and buyers, the calculus also matters. Organic products often carry premium prices, justified by environmental and health promises. But as Time magazine noted, buyers pay around 47% more for organic produce, raising questions about affordability and equity. Sustainable products, especially when transparency is ensured, might offer similar ecological benefits at a lower cost and tap into an emerging consumer desire for climate-smart food systems.

For policymakers and institutional buyers, the insight is clear: one-size-fits-all subsidies or mandates may backfire. Supporting smart financing during transition periods, bolstering eco-service payments, and validating digital sustainable standards can unlock long-term gains for farms and buyers alike. The marketplace needs flexibility, rewarding both input-based (organic) and systems-based (sustainable) models with tailored incentives.

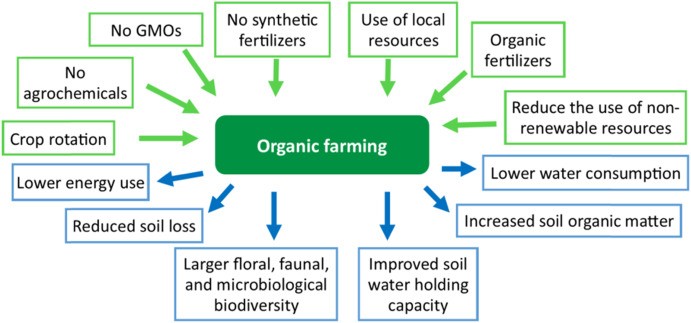

This infographic outlines the core practices and benefits of organic farming, from avoiding GMOs to enhancing soil biodiversity. It highlights how organic methods prioritize ecological balance and resource conservation within agricultural systems.

Institutional Frameworks Promoting Each

Any discussion of sustainable or organic farming must be anchored in the institutions and policies that shape them. From government ministries to multilateral agreements, the frameworks behind these models dictate how they scale, whom they benefit, and how farmers innovate on the ground.

In many countries, organic farming benefits from clear, codified standards and dedicated bureaucracies. The European Union, for example, operates under Regulation (EEC) No. 834/2007 and its successors, establishing legal definitions and inspection regimes for “organic” production.

Similarly, India’s Organic certification mark, administered through APEDA under the National Program for Organic Production, sets nationwide process-based standards. Such formal frameworks enable market certainty: consumers buying “organic” largely know what they are getting, and producers can access subsidies or export markets assured of compliance. Yet, these systems can be bureaucratic and costly, sometimes sidelining smallholders lacking capital for multi-year audits and fees.

To address these barriers, Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) have taken root in several regions. Defined by IFOAM as community-led assurance schemes built on trust and transparency, PGS empower small farmers to certify one another, helping bypass third-party audit costs while preserving integrity in local and domestic markets. They exemplify how institutional innovation can democratise certification, though their upside in export markets remains limited.

Conversely, sustainable agriculture frameworks tend to be more fragmented and modular, residing in broader environmental and rural development policies rather than organic-specific laws. At the international scale, the FAO’s Sustainable Food and Agriculture (SFA) framework underlines the triple bottom line: economic viability, environmental health, and social equity.

Country-level initiatives, such as Saudi Arabia’s Organic Agriculture Law, which contains a department, a nonprofit association, and a research centre under a unified policy, demonstrate how governments can weave organic and natural farming into institutional ecosystems.

Earth5R’s work illustrates how CSR and local partnerships can plug gaps in these frameworks. Its sustainable agriculture programs, backed by corporate social responsibility and ESG commitments, install water-efficient irrigation, community composting, and farmer training via local delivery platforms. These efforts gain farmer buy-in and create regional standards, even in the absence of formal certification mandates.

In Brazil and India, government-sponsored schemes reflect institutional hybridity. India’s Mission Organic Value Chain Development for North Eastern Region (MOVCD-NER) has mobilised eight states, 50,000 hectares, and 50,000 farmers since 2015, offering support across inputs, certification, processing, marketing, and branding.

In Haryana, the state government recently announced dedicated organic markets, storage grants, and native cow subsidies, pushing smallholders into organised value chains. In Jharkhand, officials cited Sikkim’s all-organic model as a template, urging improved farmer-buyer linkages and institutional SOPs.

Despite their promise, institutional gaps remain. A United Nations FAO-affiliated report on organic family farming emphasises that without supportive land tenure, subsidies, cooperatives, and public procurement, smallholders struggle to participate meaningfully. Similarly, Earth5R’s reliance on volunteer and CSR funding suggests that sustainable agriculture may struggle to scale without public incentives or national policy recognition.

In short, organic farming thrives under formal regulation, but risks excluding smallholders through cost and labelling complexity. Sustainable agriculture excels in flexibility and local adaptability, but risks fragmentation in the absence of centralised frameworks. Blended systems—such as India’s MOVCD-NER or Earth5R’s CSR-platform model—show promise by aligning organic standards with sustainable tools under coherent institutional umbrellas.

Why Integration May Be the Real Answer

As the complexities of food systems deepen, agricultural scholars and practitioners increasingly argue that the future lies not in choosing organic or sustainable agriculture—but in integrating their strengths to forge resilient, high-functioning farms. This hybrid vision is gaining traction, backed by a broad base of scientific evidence and real-world case studies.

One strong line of inquiry comes from meta-analyses of integrated farming systems (IFS). A comprehensive review highlighted that systems combining crops, livestock, fishery, and resource recycling often achieve 265% greater profitability and 143% more employment compared to single-enterprise farms.

These systems also significantly boost ecosystem resilience and efficiency—hallmarks of both organic and sustainable paradigms. For smallholders, such synergies can translate into increased diversity of produce, more stable income streams, and improved resource efficiency.

Another study published in Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems examined villages in Meghalaya implementing integrated organic models featuring rainwater harvesting, livestock components, and crop-livestock rotations. Not only did incomes rise, but nutrient-use efficiency and soil health improved markedly—signalling that when organic principles are expanded into broader systems, both farm performance and sustainability improve.

Earth5R’s pioneering programs echo these findings. In rural India, the rollout of a blended strategy—combining composting, crop diversity, microbial inoculants, drip irrigation, and digital tracking—led to 20–40% increases in topsoil carbon, consistent yield gains, and new income streams from carbon credits and agricultural waste. By seamlessly marrying organic integrity with precision tools, the program delivered measurable environmental benefits without rigid certification constraints.

We can liken conventional organic farming to a finely crafted handmade clock—meticulous and precise, but requiring consistent inputs and maintenance. Sustainable systems, by contrast, resemble a digital smartwatch—adaptive, data-driven, and integrated with modern tools. The integrated model is like a smart hybrid watch—decorative, functional, and capable of delivering both traditional and real-time insights.

Notably, long-term research supports hybrid outcomes. A meta-synthesis spanning five decades showed that farm diversification—using techniques like intercropping, organic amendments, and crop rotations—boosts profitability, biodiversity, soil quality, and carbon sequestration by up to 2,800% over 20 years while keeping yields stable. Diversification—long a staple of organic systems—finds new power when layered with sustainable practices.

Nevertheless, integration faces barriers. A review of IFS notes that initial investments, diversified infrastructure needs, and market constraints—such as handling mixed produce and securing buyers—can slow adoption. Additionally, without coherent institutional backing, fragmented practices may lack incentives and policy support.

That’s why institutional integration is essential. Initiatives like Earth5R’s CSR-backed digital certification, India’s MOVCD-NER, and organic/digital alliances led by ICAR signal a shift toward coherent blended frameworks that recognise multiple pathways to sustainability—uniting clean inputs, innovation, and scale.

In short, integration is less about compromise and more about synergy. Merging organic’s soil-first, chemical-free ethos with sustainable agriculture’s technological toolkit and systems thinking offers a pathway to climate resilience, farmer welfare, and food security. Instead of continuing the debate over purity, scholars and practitioners are increasingly focusing on how to craft hybrid models that optimize ecological, economic, and social outcomes simultaneously—the true hallmarks of tomorrow’s resilient agriculture.

What Governments and CSR Teams Should Prioritize

In an era when agriculture contributes nearly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions and drives over 90% of tropical deforestation, the shift toward sustainable and organic practices has become urgent, not optional (Reuters). Policymakers and CSR teams often struggle to balance immediate food production needs with long-term planetary health. However, science now points to triple-duty policies that simultaneously combat undernutrition, non-communicable diseases, and ecological degradation.

First, incentivising crop and systems diversification is crucial. Evidence from global experts and Earth5R’s field work shows that integrated models—agroforestry, mixed cropping, livestock rotations—boost soil carbon, resilience, and farmer incomes. India’s National Agroforestry Policy exemplifies this, promoting tree–crop–livestock systems to enhance productivity and ecological health.

Second, financial reforms are essential. Agriculture needs over US$1 trillion annually until 2030, yet receives under 5% of global climate finance. Redirecting subsidies toward regenerative outcomes like cover cropping and soil restoration can bridge this gap. Companies such as Diageo, Mars, and McCain are piloting regenerative investments, showing corporate willingness when policies align (WSJ).

Third, smart regulations and certifications matter. The EU’s Farm-to-Fork strategy aims to halve chemical use and double organic farmland by 2030. Supporting affordable certifications—such as Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) and digital traceability—can democratise market access and reduce greenwashing.

Fourth, institutional and community-led models amplify change. Earth5R’s “Green Points” platform lets farmers earn digital verification and carbon credits without expensive audits. Its “Green Turn” campaign reached 108,000 rural farmers, proving that knowledge-sharing catalyses sustainable adoption.

Finally, monitoring and evaluation are key. Rigorous tracking—soil carbon, water use, nutrient balance—ensures policies translate into outcomes, aligning with frameworks like the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive demanding tangible supply-chain evidence.

The analogy is clear: governments and CSR teams shouldn’t just hand farmers tools—they must build the entire workshop and fund its operation. When subsidies, regulation, certification, education, and technology converge, agriculture becomes a lever for planetary health and farmer prosperity.

In short, the future of food demands multi-layered commitments: policies with triple-duty impact, risk-sharing finance, inclusive institutions, community-powered education, and data-backed monitoring to turn promises into proof.

Towards a Resilient Food Future: Integrating Organic and Sustainable Pathways

In the debate between sustainable agriculture and organic farming, it is clear that neither stands alone as a universal solution. While organic farming prioritizes chemical-free cultivation and consumer health, sustainable agriculture offers systems-based resilience, resource efficiency, and adaptability. The real promise lies in their integration—merging organic’s purity with sustainability’s technological innovation and ecosystem approach. For farmers, consumers, policymakers, and CSR teams, the path forward must embrace hybrid models that balance ecological integrity, economic viability, and social equity. Only through this synergy can we build a food system that nourishes both people and the planet, ensuring true security for future generations.

FAQs on Sustainable Agriculture vs. Organic Farming: What’s the Difference and Why It Matters for the Future of Food

What is organic farming?

Organic farming is an agricultural system that strictly avoids synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and growth regulators. It relies on compost, crop rotations, green manures, and biological pest control to maintain soil fertility and ecological balance.

What is sustainable agriculture?

Sustainable agriculture is a broad approach focused on producing food in ways that protect the environment, maintain economic viability, and support social equity. It uses methods—organic, regenerative, or technological—that reduce negative impacts while improving farm resilience.

How are organic and sustainable agriculture similar?

Both aim to preserve soil health, reduce pollution, enhance biodiversity, and improve farmer livelihoods. They prioritise long-term ecological balance over short-term yield maximisation.

How are organic and sustainable agriculture different?

Organic farming follows strict rules banning synthetic inputs, while sustainable agriculture is flexible, adopting any method—whether organic or technological—that achieves low environmental impact and social benefits.

Is organic farming always sustainable?

Not necessarily. Although organic farming avoids harmful chemicals, it may require more land or water to achieve similar yields, which can affect sustainability at scale.

Is sustainable agriculture always organic?

No. Sustainable agriculture may use synthetic inputs if they result in lower overall environmental harm, focusing on outcomes rather than strict bans.

Why does organic certification matter?

Certification provides consumer trust, guarantees compliance with organic standards, and often allows farmers to access premium markets and prices.

Why is sustainable agriculture harder to certify?

Because it is outcome-based and context-specific, it lacks universal standards. Certification schemes like Rainforest Alliance or Fairtrade assess varied aspects such as ecosystem protection and fair wages.

Does organic farming yield less than conventional farming?

Studies show organic yields are generally 10–20% lower, although they can match or exceed conventional yields in certain crops and conditions, especially in drought years due to improved soil health.

Which is more profitable: organic or sustainable farming?

Organic farming can be more profitable due to premium prices despite lower yields. Sustainable farming improves profitability through resource efficiency, reduced input costs, and resilience to market and climate shocks.

What role does technology play in sustainable agriculture?

Technology—like drip irrigation, AI soil sensors, and precision farming tools—helps optimise input use, monitor soil health, and increase productivity without compromising environmental goals.

Can farmers combine organic and sustainable practices?

Yes. Many farmers blend organic principles with sustainable tools, such as using compost and biological pest control alongside precision irrigation and digital monitoring.

What are the environmental benefits of organic farming?

It enhances soil organic matter, increases biodiversity, reduces pollution from synthetic chemicals, and often improves ecosystem health over time.

What are the environmental benefits of sustainable agriculture?

It reduces greenhouse gas emissions, conserves water, prevents land degradation, and builds climate resilience through diversified cropping and soil regeneration.

Why is this debate important for the future of food?

Agricultural systems must feed a growing population while minimising environmental damage and ensuring farmer welfare. Understanding these models guides better policies and practices.

What are Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS)?

PGS are community-based certification schemes where farmers certify each other based on trust and transparency, making organic certification accessible for smallholders.

How do consumers view organic vs. sustainable labels?

Consumers often trust and recognise organic labels due to strict standards, while sustainable labels are seen as positive but can be confusing due to varied definitions.

What policy measures can support both models?

Policies promoting crop diversification, regenerative subsidies, affordable certification, farmer education, and technological access can integrate organic and sustainable approaches effectively.

What is an example of integrated agriculture in India?

Programs like Earth5R in Maharashtra combine composting, drip irrigation, microbial inoculants, and digital tracking to improve yields, soil health, and incomes simultaneously.

Which approach is better for small farmers?

It depends on the context. Organic farming suits areas with abundant labor and premium markets, while sustainable agriculture offers flexibility, resilience, and access to climate-smart tools without rigid input bans.

Building Resilient Food Systems Together

As we navigate the challenges of food security, climate change, and farmer welfare, it is imperative to move beyond the debate between organic and sustainable agriculture. Policymakers, researchers, corporations, and community organizations must collaborate to integrate the strengths of both models. Invest in research, support hybrid farming innovations, reform certification systems, and empower farmers with knowledge and technology. By doing so, we can build food systems that are ecologically sound, economically viable, and socially just—ensuring a resilient and nutritious future for all.

-Authored by Pragna Chakraborty