Hydrogen: The Catalyst of a New Clean Energy Era

The shift to a hydrogen economy is turning out to be one of the most audacious and science based routes toward deep decarbonization. With nations competing to achieve net-zero goals, hydrogen particularly its “green” version is a flexible carrier of energy able to connect intermittent renewable electricity with industry, transport, and long-duration storage. This article explores the science, economics, technologies, and on-the-ground tests propelling hydrogen from idea to commercial-scale deployment.

Over the past few years, prices for electrolyzers decreased as renewable power prices dropped dramatically closing the economic gap for green hydrogen. For example, India and Europe have numerous pilot programs that now produce hydrogen at competitive levels in supportive policy landscapes. But there are still issues: storage, infrastructure, lifecycle emissions, and regulatory standardization all present significant hurdles. Through peer-reviewed life-cycle analyses, techno-economic studies, and case studies, specifically from Earth5R’s activity in India, this article assesses whether hydrogen can live up to its promise.

Through the emphasis on scientific facts, actual case studies, and policy best practices, this article presents an objective, research-based analysis on whether hydrogen will serve as the foundation of tomorrow’s clean-energy infrastructure or hold a hopeful niche.

The Many Shades of Hydrogen: Decoding the Colours of Clean Energy

From humming power plants to off-grid villages, the discussion about energy’s future is changing fast and at the heart of it is a substance as basic as it is revolutionary:hydrogen. Once the domain of science fiction pages, hydrogen now is coming into focus as a universal energy carrier with the power to fill the bridge between intermittent renewable power and the heavy industry sectors that are so far still stubbornly carbon-based. The “hydrogen economy” is no longer a distant dream; it is actually being mapped by governments and firms worldwide.

In 2023 alone, worldwide hydrogen demand exceeded 97 million tonnes almost all of which presently originates from fossil fuels with zero carbon capture.

But the path is shifting. Based on McKinsey’s estimates, demand for “clean hydrogen” (made with low or zero carbon emissions) may rise to between 125 and 585 million tonnes a year by 2050.

This is not just expansion in a niche market, but possibly a revolution in the way energy is stored, shipped, and used.

However, the future is also full of technical, economic, and regulatory challenges. Hydrogen must be generated cheaply, stored safely, transported over long distances, and used by industries hesitant to reinvest. As the National Academies notes, achieving a complete hydrogen economy requires advancement across each connection: “production, transportation, storage, and end use.”

Take the example of Japan’s Fukushima Hydrogen Energy Research Field (FH2R) where a 10 MW solar-powered facility is making hydrogen and showing how local renewables can supply big-scale hydrogen systems.

These pilot projects ground lofty visions in practical engineering. In India, Earth5R has mapped how government initiatives and climate goals are already stimulating private investment into green hydrogen, especially in the agribusiness and industry sectors.

In this article, we interweave scientific research, techno-economic analyses, and in-the-field case studies to address an urgent question: Is hydrogen on the path to becoming the pillar of a clean energy age, or is it a promising detour in the quest for decarbonization?

From molecular interactions to policy tools, from airports to fertilizer factories, we will unravel hydrogen’s promise and pitfalls in the decades to come.

Engineering the Future Fuel: The Evolving Science of Hydrogen Production

Hydrogen is the lightest element in the universe, but extracting it from water, gas, or biomass is not simple. The promise of a hydrogen economy comes from decades of work in chemical engineering, materials science, and system integration. At its core, hydrogen production involves breaking molecular bonds, whether in water (H₂O) or hydrocarbons (CH₄, coal). The goal is to do this with minimal energy loss and carbon emissions.

Currently, the most common method is steam methane reforming (SMR). In this process, high-temperature steam reacts with methane to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide. SMR is a well-established industrial method, making it cost-competitive; however, it releases a large amount of CO₂ unless combined with carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). The effectiveness of SMR with CCUS relies heavily on capture rates, which should ideally exceed 90%, and effective leakage control. Any methane leaks can offset benefits. If executed properly, blue hydrogen can provide a lower-carbon option, but it is influenced by assumptions about capture durability, energy losses, and lifecycle emissions.

Another key method is electrolysis. This process uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. Many researchers view this as the cleanest long-term option, particularly when combined with renewable energy. The main types of electrolyzers include alkaline, proton exchange membrane (PEM), anion exchange membrane (AEM), and solid oxide electrolyzers (SOE). Their efficiencies typically range from 60% to 90% under ideal conditions, though actual performance is often lower. Each technology has its pros and cons. Alkaline systems are more common and cheaper but less adaptable to variable power. In contrast, PEM systems are more flexible but more expensive. SOE performs well when high-temperature heat sources are available.

In some cases, high-temperature electrolysis (HTE) or steam electrolysis operates at elevated temperatures (often above 600 °C), using both heat and electricity. By shifting some energy requirements from electricity to heat, which can be more affordable or come from waste heat, overall efficiency may improve.

Beyond traditional methods, researchers are examining new and hybrid approaches. Methane pyrolysis, or “turquoise hydrogen,” breaks down methane into hydrogen and solid carbon, avoiding CO₂ emissions if the carbon is sequestered or used. Thermochemical cycles, such as the copper–chlorine (Cu–Cl) or ceria redox cycles, utilize high-temperature chemistry and cyclic reactions to split water without relying on fossil fuels. The Cu–Cl cycle involves four steps that combine thermal and electrochemical processes; it shows promise due to its moderate temperature needs (around 500 °C) and ability to integrate waste or nuclear heat. Other thermochemical methods involve ceria or metal oxides in high-temperature loops.

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting is another area of research. This method uses sunlight, often through semiconductor electrodes, to directly drive water splitting. Some experimental PEC systems are now achieving solar-to-hydrogen efficiencies of 7% to 10%.

Biological and bioelectrochemical processes, like electrohydrogenesis, use microbes to convert organic matter into hydrogen at low voltage, but these remain largely in the lab phase.

To illustrate, think of hydrogen production as creating water by baking evaporated water. The traditional SMR process resembles boiling saltwater, capturing most of the vapor but leaving behind a salt residue (CO₂). Electrolysis is similar to using solar heat to evaporate pure water and then recondensing it clean but energy-intensive. Thermochemical cycles operate more like a smart multi-stage distillation, reusing heat and chemicals to cut down on waste.

The maturity of these scientific methods varies. SMR has been around for decades and is commercially proven, while electrolysis is rapidly scaling up. Thermochemical and PEC processes are mostly still in pilot or demonstration phases. Over time, advancements in catalysts, materials (especially for durability), integration with renewable heat, and system scale will determine which production methods become dominant.

In the next section, we will explore how hydrogen is stored and transported, as producing it is just the first step in the process.

Storage, Transport & Distribution: Transporting Hydrogen from Production to Point of Use

If hydrogen is to serve its function in a future of clean energy, the way we store, transport, and distribute it comes almost as close in importance to the way we make it. Hydrogen is so light and diffuse a substance, and therefore transporting it from location to location or having it available for use challenges even the most sophisticated industrial systems with engineering, energy, and safety issues.

One of the simpler methods is storage in compressed gas, where hydrogen is compressed into high-pressure tanks (usually 350–700 bar). While mature, it has the disadvantage of low volumetric energy density: it takes lots of tanks to store a modest quantity of hydrogen. Efficiency is also devoured by compression energy and heat losses. Efforts to reduce weight (for mobile applications) involve composite materials and liner design, but the balance between strength, permeability, and cost is hard to strike.

Alternatively, liquefied hydrogen keeps the gas at cryogenic temperatures (~ –253 °C). Density is increased but brings with it the issue of boil-off (hydrogen slowly vaporizing), loss through insulation, and sophisticated cooling systems. For long time periods, the losses become non-negligible. Most large scale storage or transport systems (e.g., for aerospace or long distance shipping) pursue this avenue notwithstanding the engineering challenges.

Some processes convert hydrogen into chemical or material carriers for more secure—or denser—transport. Metal hydrides, for example, take up hydrogen into a solid lattice (e.g., magnesium hydride) and release it upon heat. But achieving good kinetics (rapid absorption/desorption) and high gravimetric capacity is of intense research interest.Next come liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) liquids that chemically store hydrogen and can be transported in ordinary tanks and pipelines. When necessary, they are dehydrogenated to yield pure hydrogen. LOHC pipelines, when heated, can achieve cycle efficiencies of 60–90 %. For instance, Japan already tests LOHC supply chains between Kawasaki and Brunei. For extremely large quantities, geological and underground storage (e.g. in depleted gas reservoirs, salt caverns, or saline aquifers) is actively being explored.

But maintaining purity, leakage management, and mitigating microbial and geochemical impacts are critical issues. Experimental research indicates that capillary trapping, gas mixing with residual gas, and biofilms may impair performanceTransport itself typically occurs through pipelines, tanker trucks, or ships. Pipelines are cost-effective for runs below 1,000–1,500 km, but hydrogen’s high diffusivity, material embrittlement, and leak hazards require specially developed steels or liners. At times, hydrogen is mixed with natural gas in current pipelines with experiments (up to ~5–15 % volumetric) aimed at decreasing infrastructure expenses, but the separation and safety have to be effectively controlled. For distances of greater lengths or for cross-sea transport, liquid hydrogen carriers or LOHC shipping are novel alternatives. To put it in analogy: suppose you possess valuable perfume (hydrogen) that you need to transport worldwide. You can either transport it in pressurized spray cans (compressed gas), freeze it into frozen solid (liquid hydrogen), or lock it in a less flammable liquid that you extract again later (LOHC). All have strengths and weaknesses in terms of weight, price, loss, and speed.

In all instances, these storage and transportation phases burn energy and have losses, making the net efficiency of hydrogen as an energy vector decrease. To overcome this “hidden cost” is one of the grand challenges in engineering for a viable hydrogen economy.

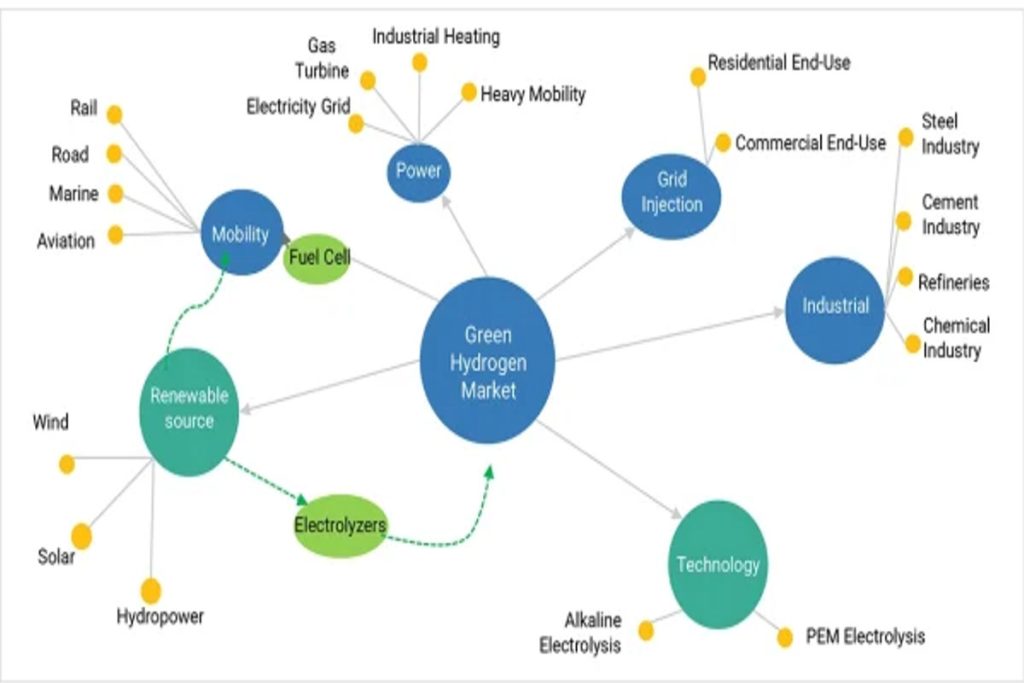

End-Use Applications: Where Hydrogen Meets Real Demand

Hydrogen is changing from an industrial feedstock into a key part of future energy systems based on how and where we use it. Recently, scientists and engineers have moved hydrogen out of academic settings and into real world applications that could transform heavy industry, transport, and energy grids. The main question is no longer if we will use hydrogen but how extensively and effectively we will do so.

Currently, hydrogen’s most common role is as a chemical feedstock. In fertilizer and ammonia production, the Haber-Bosch process combines nitrogen with hydrogen to create ammonia. More than half of the world’s hydrogen is used this way today. Clean hydrogen has the potential to decarbonize this area. Using green hydrogen instead of grey hydrogen could significantly reduce CO₂ emissions related to global food production.

However, hydrogen’s potential goes well beyond chemistry. In the steel and cement industries, hydrogen is being tested as a high-heat, zero-carbon alternative to coke and coal. By replacing carbon in the reduction processes or providing thermal energy, hydrogen could help cut down emissions in some of the hardest-to-tackle industries. Many pilot projects in Europe and Asia are now looking at hydrogen-based direct reduction of iron (H-DRI) processes.

Transportation is an area where hydrogen often makes the news. Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) use hydrogen and oxygen in a fuel cell to create electricity, producing only water vapor as exhaust. These vehicles are particularly promising in heavy-duty freight, buses, and trains, where battery energy density becomes a limitation. In Japan, the Hydrogen Highway project has added hydrogen filling stations throughout the country to support an emerging FCEV fleet. Meanwhile, the FV-E991 “HYBARI” fuel cell train in Japan is an experimental electric multiple unit (EMU) that combines batteries and hydrogen systems to test zero-emission rail service.

The maritime and aviation industries, often seen as difficult to decarbonize, are also turning to hydrogen and hydrogen-derived fuels. In shipping, hydrogen and ammonia are being researched as fuels for fuel cells or modified combustion engines, especially for short-sea routes or ferries. However, challenges such as energy density, storage, and infrastructure still exist. In aviation, hybrid systems that combine hydrogen fuel cells and batteries are being explored in regional aircraft. This approach offers a way to reduce emissions on shorter routes where using batteries alone is not enough.

Hydrogen also contributes to grid balancing and long-duration energy storage. Surplus renewable electricity can drive electrolysis, turning excess energy into storable hydrogen. This hydrogen can then be converted back into electricity using fuel cells or turbines. Essentially, hydrogen acts like a large molecular battery, able to store and deliver energy over hours, days, or even seasons, helping to smooth out the inconsistencies of wind and solar energy.

To illustrate this, picture a future city where electricity from rooftop solar panels powers homes during the day. Excess electricity is converted into hydrogen in the afternoon and stored in underground caverns. At night, or when it’s cloudy, that stored hydrogen is used through fuel cells to power buildings, trucks, or trains. This makes hydrogen a flexible energy currency that can be transferred across different sectors and locations.

The potential is enormous, offering zero emissions, energy flexibility, and significant decarbonization . Still, challenges remain in terms of cost, infrastructure, purity standards, and system integration. In the next section, we will look into how hydrogen’s environmental and climate impacts vary throughout its entire lifecycle.

Environmental & Climate Impacts: Weighing Hydrogen’s Promise Against Its Footprint

Hydrogen often appears to be a climate savior, as it is a zero-emission fuel at the point of use. However, its real environmental impact is shaped by its entire lifecycle, from feedstock extraction to final consumption. We must look at scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, water use, and leakage risks to truly evaluate whether hydrogen fulfills its green promise.

A key issue arises with blue hydrogen, which is produced through steam methane reforming with carbon capture. While CO₂ emissions from the plant may drop significantly, methane leaks and hydrogen leaks can undermine or even eliminate the climate benefits. A recent study shows that in extreme leakage scenarios, blue hydrogen might actually lead to more warming in the short term compared to fossil fuels. However, when methane and hydrogen emissions are extremely low, blue hydrogen can reduce warming impacts by 60 to 85 percent.

In contrast, green hydrogen, created through electrolysis powered by renewable energy, shows much better lifecycle results. Under low-emission conditions, it can achieve 91 to 95 percent reductions in climate impact compared to fossil fuel systems. Yet, even in this case, a high hydrogen leak rate (around 10 percent) can cut those reductions by up to 25 percent.

Beyond greenhouse gases, the methods of hydrogen production also affect water use, land requirements, and the materials needed. Electrolytic systems, especially on a large scale, require substantial amounts of purified water, which could burden areas with limited water supplies. Material inputs, such as precious metals for PEM stacks or rare elements in catalysts, also lead to upstream emissions and strain the supply chain.

Another developing option, methane pyrolysis (turquoise hydrogen), turns methane into hydrogen and solid carbon, avoiding CO₂ emissions. Lifecycle assessments of advanced pyrolysis methods indicate carbon intensities roughly 91 percent lower than traditional steam methane reforming. However, challenges remain. The need for markets for large amounts of solid carbon byproduct, the materials for high-temperature reactors, and energy integration all impact its environmental feasibility.

The transportation and distribution stages also affect total emissions. For example, a pipeline bringing hydrogen from Morocco to Germany may add 0.07 to 0.11 kg CO₂e per kg H₂ in transit emissions. More distant routes, like those from Nigeria, could add as much as 0.27 to 0.38 kg CO₂e per kg delivered. Truck or liquefied transport increases emissions further.

In summary, hydrogen’s climate benefits depend more on the cleanliness of its upstream supply chain than on the gas itself. Reducing methane leaks, improving process efficiencies, and optimizing system performance are just as important as selecting a “green” label. Only by managing every aspect can hydrogen’s potential as a low-carbon fuel for the future become a reality.

The Price of the Future: Economics, Costs, and Market Forces Driving Hydrogen

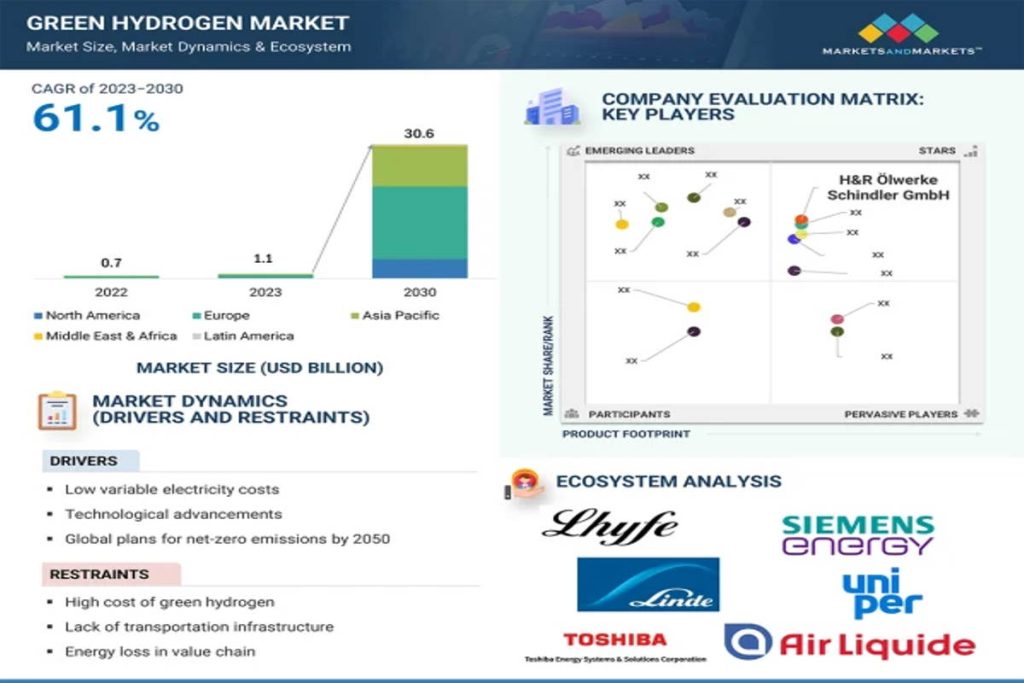

Hydrogen’s role in the clean energy transition depends on both chemistry and cost factors. The economics of hydrogen are changing quickly due to falling renewable power prices, government support, and the increasing production of electrolyzers. Despite this optimism, reaching price parity with fossil fuels remains the biggest challenge for the industry.

Currently, the price of grey hydrogen, which is made from natural gas, ranges from $1 to $2 per kilogram. This makes it the least expensive and most commonly used type. However, it has a significant carbon footprint. Blue hydrogen, produced from the same feedstock with added carbon capture, usually costs between $1.5 and $3 per kilogram, depending on the capture rate and local gas prices. On the other hand, green hydrogen, which comes from renewable-powered electrolysis, currently costs between $4 and $8 per kilogram. However, projections from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) indicate that costs could drop below $1.50 per kilogram by 2030 due to technological advancements and cheaper renewable sources.

The decreasing prices of solar and wind energy have become the main driver in the market. As renewable energy becomes more affordable, the cost of input energy for electrolysis, which was once the largest expense, is also falling. Countries like India, Australia, and Morocco are leveraging their abundant renewables to aim for green hydrogen exports to Europe and East Asia. Likewise, the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act and the European Union’s Hydrogen Bank are investing billions in subsidies, tax credits, and purchase agreements to make green hydrogen commercially viable.

However, even with these subsidies, bringing hydrogen from the lab to the market involves more than just financial aspects; it also includes infrastructure challenges. Constructing electrolyzer gigafactories, storage facilities, specialized pipelines, and refueling stations requires long-term investment and confidence from investors. Analysts caution that without consistent demand from industries like steel, fertilizer, and heavy transport, prices might not drop quickly enough to attract private funding. This is where policy measures, such as carbon pricing, green procurement mandates, and hydrogen purchase agreements, are crucial in creating market demand.

The economic journey of hydrogen mirrors that of the early solar industry. Two decades ago, solar energy was considered too expensive. Today, it stands as the cheapest source of new electricity ever. If hydrogen follows a similar path through increased scale, innovation, and smart policies, it could become the “oil of the net-zero era,” powering industries and nations for years to come.

Guardrails for the Hydrogen Age: Safety, Standards, and Regulation

The possibilities for hydrogen as a clean energy carrier are enormous, but so are the technical demands on storing it safely and uniformly. Since hydrogen is the lightest and smallest molecule, it acts differently from any other traditional fuel it flows quickly, leaks through minuscule crevices, and burns more readily if combined with air. This is why safety engineering and regulatory control are gradually becoming the pillars of credibility for the hydrogen economy.

Contemporary hydrogen systems also rely strongly on learning from the industrial gas industry, which has worked with hydrogen for more than a century in petroleum refineries and chemical plants. But the scope of upcoming applications from automobiles and residences to pipes and harbors requires new paradigms for public safety. Countries like Japan, Germany, and the United States are creating comprehensive codes and standards, like ISO 19880 for hydrogen fuel stations and NFPA 2 in the United States, that regulate storage pressures, leak detection, and fire protection

Increasing attention is on materials and infrastructure integrity. Hydrogen embrittlement in which metals become brittle when exposed adds real danger to pipelines and storage tanks. New alloys, polymer coatings, and ongoing surveillance are now all part of the safety plan for hydrogen transport networks. The European Commission and the International Energy Agency are financing joint programmes to standardise these around the world, aware that pan-European trade will be unthinkable without common rules.

In reality, the success of the hydrogen economy relies not only on the creation of clean fuel, but on building public trust. Just as safety in aviation turned flight from a dangerous novelty into the globe’s safest form of transport, so hydrogen as well will require decades of harmonized regulation, engineering watchfulness, and open-to-view monitoring before it can energize the world with assurance.

Bridging Innovation and Implementation: Technology Readiness, Barriers, and R&D Needs

While hydrogen is often seen as the energy of the future, its technological readiness varies. It ranges from laboratory prototypes to fully developed industrial systems. According to the International Energy Agency, most hydrogen production through steam methane reforming (SMR) and basic industrial uses are at Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) 8 to 9. This means they are proven and widely used. In contrast, emerging technologies such as solid oxide electrolysis, photoelectrochemical splitting, and methane pyrolysis remain in the TRL 4 to 6 range. They are still in pilot or demonstration stages.

One major barrier is the cost and durability of electrolyzers. This is especially true for proton exchange membrane (PEM) and solid oxide systems. Electrolyzers face limitations due to expensive materials like platinum-group catalysts and the degradation of membranes when under high loads. Researchers in Europe and Asia are working hard to create low-cost alternatives using nickel, iron, or cobalt composites while also improving the longevity of these systems. Similar challenges exist in hydrogen storage and fuel cell technology. Efficiency, weight, and scalability continue to hinder commercial competitiveness.

Another challenge is the lack of infrastructure. Unlike natural gas or oil, hydrogen needs new pipelines, compressors, and refueling stations. Retrofitting existing systems is technically possible. However, it requires thorough safety testing to avoid leaks and embrittlement. The European Union’s “Hydrogen Backbone” initiative and Japan’s hydrogen corridor projects are early efforts to address this. They aim to build shared, standardized infrastructure across borders.

The future depends on significant R&D funding and international collaboration. Just as the solar industry’s costs dropped over decades of research and increased production, hydrogen needs ongoing innovation in materials, catalysts, digital monitoring, and heat integration. This will help it move from promise to profit. Hydrogen is at a similar point as solar power was twenty years ago, where science meets market momentum, and innovation will determine who leads the next energy revolution.

Mapping the Hydrogen Horizon: A Global and Regional Market Outlook

The international hydrogen market is entering an era of unprecedented momentum, driven by government policy, private capital, and the quest for net-zero emissions. Over 40 national hydrogen strategies are now established, backed by hundreds of pilot projects and over $500 billion of announced investment up to 2030. A niche energy carrier of the past is quickly becoming a focus of industrial and geopolitical planning.

In Europe, it is the most powerful. The European Union Hydrogen Strategy will generate 10 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen per year by 2030, in conjunction with imports from Morocco, Namibia, and Australia. Initiatives such as the European Hydrogen Backbone intend to link supply and demand hubs within regions with a 40,000-kilometer network of pipelines by mid-century. Germany, in specific, is placing its hopes on green hydrogen imports to decarbonize its chemical and steel sectors and is joining hands with countries in the Middle East and Africa.

Japan and South Korea are at the forefront of the Asia-Pacific with mass-scale fuel cell adoption and global supply chain collaborations. Japan’s Kawasaki Hydrogen Road and Australia’s Asian Renewable Energy Hub are just two instances of long-term strategic planning to make and export green hydrogen across the Pacific. India has been another recent entrant with the National Green Hydrogen Mission focusing on production at a cost of less than $1 per kilogram and building in country manufacturing capacity for electrolyzers

In the Americas, the United States is becoming a hydrogen superpower by establishing the Hydrogen Hubs Initiative under the Inflation Reduction Act, which invests $7 billion in regional hydrogen production clusters . Chile and Brazil in Latin America are also becoming green hydrogen export countries owing to favorable wind and solar resources.

The overall scenario looks like an emerging trade map—a network of production centers, maritime pathways, and policy structures coming together into the “hydrogen geopolitics” of the 21st century, as described by some analysts. Just as with oil in the previous century, hydrogen is set to reshape energy alliances, regional competitiveness, and the economic power balance of the decarbonized world.

Case Studies in Action: Earth5R and Beyond

Real-world experiments and pilot projects are the ultimate test of hydrogen’s promise, and Earth5R’s work in India provides powerful examples of how policy, community, and technology can converge to build a sustainable energy future. At the same time, international case studies reveal how these early initiatives connect to a broader global shift toward a hydrogen-powered economy.

In India, one of the most notable examples highlighted by Earth5R is its analysis of the nation’s growing green hydrogen investments, strengthened by supportive government policies. As reported in Earth5R’s feature on India’s clean energy transition, major corporations have committed billions of rupees toward electrolyzer manufacturing, hydrogen production, and fuel cell deployment. This surge reflects how the National Green Hydrogen Mission and favorable fiscal incentives such as subsidies, low-interest loans, and streamlined regulatory approvals are accelerating industrial participation and innovation. These developments underline a broader truth: well-designed policies can make the difference between technological stagnation and transformative progress.

Another striking dimension of Earth5R’s work lies in its Agri-Energy Alliance initiative, which explores the connection between hydrogen and sustainable agriculture. Through this model, clean hydrogen can be used to synthesize carbon-free ammonia fertilizers or power fuel-cell-driven tractors and irrigation systems, reducing emissions in one of the world’s most resource-intensive sectors. As described in Earth5R’s report on renewable integration in farming, this creates a new vision where rural communities become both producers and consumers of clean energy, aligning agricultural productivity with environmental responsibility.

While India’s momentum is promising, it mirrors a global pattern. In Australia, the Darwin Hydrogen Hub spearheaded by TotalEnergies aims to produce roughly 80,000 tonnes of green hydrogen annually, demonstrating how renewable rich yet remote regions can reinvent themselves as export powerhouses for clean energy. Similarly, in South Korea, the Ulsan Green Hydrogen Town represents one of Asia’s most integrated hydrogen ecosystems, combining production, underground pipeline distribution, and residential applications across an industrial cityscape . In Europe, Denmark’s Lolland Hydrogen Community remains a pioneer in wind-to-hydrogen systems, where surplus wind energy is converted to hydrogen, stored, and reused locally through fuel cell combined heat-and-power units, ensuring efficient utilization of renewable resources

Taken together, these projects illustrate a vital lesson: there is no single blueprint for scaling hydrogen. India’s policy-led and community driven model, Australia’s export-oriented hub, South Korea’s urban hydrogen network, and Denmark’s decentralized renewable integration each represent unique pathways shaped by local strengths and needs.

Bringing Earth5R’s insights into dialogue with these global experiments paints a richer picture, one where hydrogen’s progress depends not only on technology, but on the coordination of people, geography, and policy. It is in this orchestration that hydrogen moves from promise to practice, turning isolated innovations into a connected, resilient clean-energy ecosystem.

Closing the Gaps: Policy, Research, and the Roadmap to a Hydrogen Future

Hydrogen’s emergence from laboratory curiosity to world energy pillar is gaining speed but the journey forward is still dotted with research gaps and policy blind spots. Researchers and policymakers today concur that unless there is a planned roadmap, hydrogen may face the risk of turning out to be another patchy climate solution amazing in promise but irregular in application.

At the research frontier, the most pressing need lies in lowering the cost and improving the durability of electrolyzers and fuel cells. Many current systems rely on rare materials such as iridium and platinum, which drive up prices and supply chain risks. Research institutes, including the U.S. Department of Energy’s Hydrogen Program and Europe’s Clean Hydrogen Partnership, are funding alternative catalysts and membrane materials that could cut costs by 70% within the decade. Another vital field is hydrogen storage, where scientists are exploring solid-state materials and liquid carriers that balance safety with high density technologies in their early stages but crucial for world transport networks.

Policy, meanwhile, must catch up with technology. Experts argue that the hydrogen economy cannot thrive on innovation alone; it needs market certainty. Carbon pricing, long-term offtake agreements, and production-based incentives can ensure investors see predictable returns. For example, the European Hydrogen Bank has introduced fixed premium auctions to guarantee demand, while India’s Green Hydrogen Mission offers direct incentives per kilogram of green hydrogen produced. These steps are designed to drive the market from pilot projects into full commercial scale.

The path forward needs a three-step strategy: near-term prioritizing of cost reduction and scaling of pilots; medium-term infrastructure expansion and international trade corridors; and long-term integration of hydrogen in multi-sector decarbonization approaches. As the International Energy Agency observes, coordination is key, hydrogen’s potential will be theoretical if production, storage, transport, and demand do not develop together.

In essence, the life of hydrogen is akin to putting together an orchestra every part, from policy to research, has to play in harmony. That way alone will the symphony of clean energy achieve its resonance, turning hydrogen into a hopeful note of a global chorus of sustainability.

From Promise to Practice—The Road to a Hydrogen-Powered World

Hydrogen stands at a defining crossroads no longer a distant vision, but not yet a dominant reality. As the world races toward net-zero, hydrogen’s flexibility across industries and regions gives it a unique edge. It can decarbonize sectors that electricity alone cannot reach such as steelmaking, long-haul transport, and chemical production while providing long-term energy storage that balances renewable grids . However, its realization is contingent on translating technological potential into available practice.

The challenge is not scientific potential, it is scale, cost, and integration. Just as solar and wind had to fight before achieving cost parity, hydrogen will have to go through its own period of innovation, policy encouragement, and infrastructure investment. Governments, industries, and communities will have to cooperate in bridging the cost chasm and creating mutual systems of safety, certification, and trade. Other countries like Japan, Germany, and India are already beginning to demonstrate that early investment and strategic policy alignment can turn ambition into concrete advancement.

In some respects, hydrogen reflects the tale of the new energy revolution where dreams intersect with determination. It will not displace all sources of energy, but it will reshape the way clean energy travels, stores, and powers the world. If carefully fostered, hydrogen might not only become an energy molecule, but a beacon for the world’s collective determination to build a cleaner, more resilient future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on the Hydrogen Economy: The Future of Clean Energy

What is the hydrogen economy?

The hydrogen economy is an integrated energy system in which hydrogen serves as a vital fuel and energy carrier. It ties together renewable power generation, industrial application, transport, and long-term energy storage to facilitate deep decarbonization.

Why is hydrogen a clean energy source?

Hydrogen is clean because when it is used in fuel cells or burned, it creates only water as a waste product. Its overall environmental impact, though, is contingent on how it is generated—green hydrogen from renewable energy is almost emission-free.

What are the primary forms of hydrogen?

Hydrogen is color-coded by type: grey (from natural gas), blue (from natural gas with carbon capture), green (from renewables-powered water electrolysis), turquoise (from methane pyrolysis), and pink (from nuclear-powered electrolysis).

How is hydrogen made from water?

Hydrogen is made by electrolysis, a method that separates water into hydrogen and oxygen through electricity. With solar or wind power, it produces green hydrogen with very little carbon emissions.

Why is green hydrogen more costly than others?

Green hydrogen is pricey since electrolysis machinery and clean energy inputs are also pricey. With decreasing prices of renewable power and electrolyzer prices, the cost will substantially decline by 2030.

How is hydrogen stored?

Hydrogen may be stored as compressed gas, liquid cryogenically, or absorbed in substances such as metal hydrides and liquid organic carriers. Each has its cost, safety, and energy efficiency balance.

Is hydrogen transportable through the existing gas pipeline infrastructure?

Yes, in small blends. Hydrogen can be blended with natural gas (about 5–15%) within existing pipelines. Special materials are needed for dedicated hydrogen pipelines to avoid leakage and metal embrittlement.

What are the principal applications of hydrogen today?

Presently, hydrogen has mainly been applied in oil refining, making ammonia, and chemical production. New uses involve steel production, long-distance trucking, aviation fuel, and grid energy storage.

How does hydrogen reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

Hydrogen reduces greenhouse gas emissions by substituting fossil fuels in industrial processes and for transportation. When made from renewables, it eliminates CO₂ emissions and enables sectors that are difficult to electrify.

What are the environmental impacts of hydrogen?

Production of hydrogen can still release CO₂ when fossil fuels are employed. Water consumption for electrolysis and possible hydrogen escape, which is an indirect influence on the atmosphere, are other environmental factors to consider.

Is hydrogen safe as a fuel?

Hydrogen is combustible but dissipates rapidly since it is the lightest of gases. Advanced safety equipment, sensors, and rigorous standards guarantee its handling, storage, and transport with safety.

What are the key barriers to hydrogen uptake?

The key barriers include high production costs, a lack of infrastructure for storing and distributing, low technological readiness in new processes, and lacking policy coordination among nations.

Which nations are at the forefront of hydrogen development?

Japan, Germany, Australia, South Korea, the United States, and India are leading with national hydrogen plans, massive-scale manufacturing centers, and global trade initiatives.

How are governments assisting hydrogen?

Governments are offering subsidies, tax relief, and public-private collaborations. Initiatives such as the U.S. Hydrogen Hubs Initiative, the EU Hydrogen Bank, and India’s Green Hydrogen Mission are fueling early market expansion.

What is the contribution of Earth5R towards hydrogen awareness?

Earth5R has charted India’s nascent hydrogen ecosystem, including government support and green hydrogen use in agriculture and integration of clean energy at the community level.

Will hydrogen displace all fossil fuels?

Not quite. Hydrogen will supplement but not substitute electricity. It works best where direct electrification is not efficient, like in steel production, shipping, and aviation.

What are hydrogen fuel cells and how do they work?

A hydrogen fuel cell uses hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity with water and heat as the only byproducts. It’s commonly employed in fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) and backup power systems.

How does hydrogen assist renewable energy systems?

Hydrogen is a medium of energy storage. Surplus electricity from renewables can be reformed into hydrogen and held for future use, helping stabilize the power grid and provide power during low-production periods.

What are the most important research areas to focus on?

The principal research priorities are cheaper electrolyzers, better hydrogen storage practices, less material reliance on rare metals, and establishing large-scale, secure transport infrastructure.

What is the long-term future of hydrogen in energy systems worldwide?

The long-term vision is for hydrogen to be a pillar of the net-zero transition—connecting renewable power, decarbonized industry, clean transportation, and global energy exchange into a single integrated low-carbon economy.

Powering the Planet Responsibly — The Next Step in the Hydrogen Revolution

The future of clean energy will not be shaped by ambition alone, but by decisive global action. The hydrogen economy has moved from theoretical promise to practical potential, standing today as one of the most powerful tools to achieve deep decarbonization. What remains is the collective resolve to scale it responsibly, inclusively, and intelligently.

Governments must continue to bridge policy and innovation expanding subsidies, research funding, and international cooperation to accelerate hydrogen adoption. Industries must invest in infrastructure, green supply chains, and long-term offtake agreements that make clean hydrogen commercially viable. Meanwhile, academic institutions and sustainability organizations like Earth5R must ensure that these advancements translate into community level impact, connecting national energy goals with everyday livelihoods.

Hydrogen offers more than a path to net zero; it represents a chance to redefine global energy justice, bringing clean power to both advanced and developing economies. Every nation, every company, and every citizen has a role in this transition. The hydrogen revolution will succeed not through competition, but through collaboration and shared responsibility. The world stands at an inflection point: what we do in this decade will determine whether hydrogen becomes the fuel of the future or a missed opportunity in humanity’s quest for a cleaner planet.

Authored By- Sneha Reji