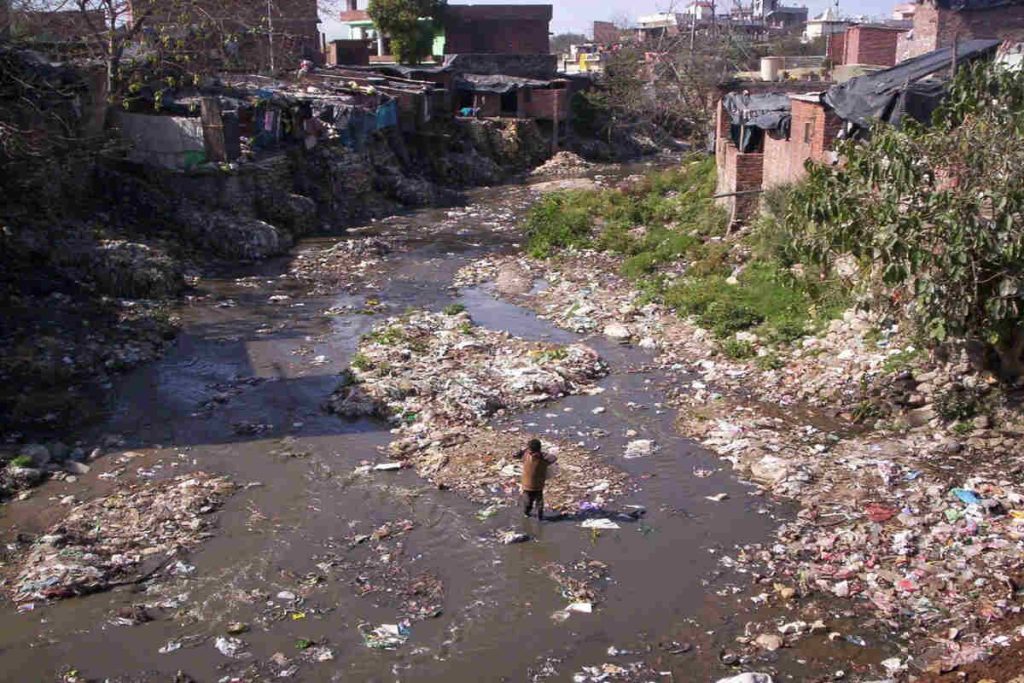

India’s rivers are more than water bodies; they are living symbols of ecology, culture, and spirituality. Yet, decades of industrialization and urbanization have left many of them critically polluted. According to the CPCB’s 2022 assessment, about 46% of the 603 monitored rivers (i.e., 279 rivers) contained at least one stretch classified as polluted.

Amid this grim reality, a handful of rivers stand out as rare examples of cleanliness and ecological resilience. From the crystal-clear waters of Umngot in Meghalaya to the protected stretches of Chambal in Madhya Pradesh, these rivers showcase what is possible when geography, governance, and community participation align.

This article takes a look at India’s 10 cleanest rivers, combining field research, scientific reports, and case studies to highlight what keeps them pristine and what threatens them.

Why “Clean Rivers” Matter; Concepts, Metrics & Indian Context

Defining “Clean” in a River Context

What does “clean” really mean when describing a river?

Scientists use a range of Water Quality Indicators, such as:

- Dissolved Oxygen (DO): a minimum of 6 mg/L is ideal for aquatic life.

- Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD): measures organic pollution; <3 mg/L indicates clean water.

- pH:neutral to slightly alkaline range (6.5–8.5).

- Water Quality Index (WQI) : a composite score that integrates parameters into a single value.

India’s River Pollution Landscape

Urban areas in India generate approximately 72,000 MLD of sewage, but only 28–30% of this gets treated. The remainder is often discharged untreated into rivers, lakes and groundwater.

Despite major initiatives like Namami Gange, progress remains uneven. While some stretches have seen dramatic improvement ,notably in the upper Ganga, many rivers continue to fail quality norms.

This makes the study of cleaner rivers not just an environmental exercise but a policy benchmark for what works.

Methodology: Selecting the Cleanest Rivers

The ten rivers selected in this feature were chosen based on:

- Documented WQI or BOD/DO levels from CPCB or peer-reviewed research.

- Protected or low-disturbance ecosystems.

- Verified mentions in scientific and government publications as “clean”.

- Evidence of community stewardship or policy success.

Each river below is presented with its geography, data highlights, and sustainability factors showing India’s natural blueprint for cleaner water systems.

The 10 Cleanest Rivers in India: Case Studies

1. Umngot River (Meghalaya)

Often called “Asia’s cleanest river,” the Umngot River near Dawki in Meghalaya looks like glass boats appear to float on air. Its remarkable clarity stems from minimal pollution sources and strict community waste control.

Local tribes, particularly in Mawlynnong village (dubbed “Asia’s cleanest village”), maintain zero tolerance for littering. The river’s catchment is surrounded by dense forests, and industrial discharge is virtually absent.

While formal WQI data is limited, tourism boards and environmental NGOs have documented transparency levels exceeding 8 meters underwater visibility

Case Study:

Community-led waste bans and ecotourism guidelines have kept Umngot pollution-free, illustrating that grassroots governance can outperform formal regulation.

2. Chambal River (Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh)

Flowing through the National Chambal Sanctuary, the Chambal River supports endangered species like the gharial and Gangetic dolphin.

A 2009 ecological survey classified the sanctuary stretch as oligosaprobic, meaning very low organic pollution

Key reasons for its cleanliness:

- Protected area status (425 km stretch).

- Minimal industrial encroachment.

- Strong enforcement of anti-poaching and pollution rules.

Case Study:

The Gharial Conservation Project (WWF-India, 2010) shows how biodiversity conservation and river cleanliness reinforce each other, a model for other river basins.

3. Teesta River (Sikkim / West Bengal)

Originating from the Teesta Khangse glacier, this river remains clean in its upper reaches before urbanization begins downstream.

According to a ScienceDirect study (2019), water samples from Sikkim recorded ion concentrations well within WHO standards (ScienceDirect, 2019).

However, midstream hydropower construction poses risks. NGOs like Earth5R are promoting sustainable river basin management, advocating green hydropower, and riparian vegetation restoration (Earth5R, 2022).

Case Study:

The “Revive Teesta” citizen campaign in 2022 mobilized students and local bodies to monitor pollution integrating technology and tradition.

4. Narmada River (Madhya Pradesh / Gujarat)

The Narmada River, India’s fifth-longest, holds spiritual and ecological importance.

Recent studies show moderate to good water quality in most upper and middle stretches. A 2023 IWA Water Supply paper applied the Fuzzy Water Quality Index (FWQI), confirming that DO and BOD levels remain within Class B (bathing quality) for many segments (IWA, 2023).

Case Study:

In 2019, the Narmada Parikrama Yatra; a citizen initiative, audited 200 ghats and reported visible water clarity improvement in 70% of sites, largely due to sewage diversion schemes.

5. Bhagirathi River (Uttarakhand)

A sacred headstream of the Ganga, the Bhagirathi originates from the Gangotri glacier and flows through relatively untouched Himalayan zones.

A 2024 BMC Geochemical Transactions study reported that the upper Ganga Basin recorded a 93% improvement in certain parameters post-COVID lockdown due to halted human activities (BMC,).

Case Study:

The Namami Gange initiative has strengthened monitoring stations near Uttarkashi. Water here routinely falls under Class A, suitable for drinking after disinfection.

Clean headwaters like Bhagirathi show that natural flow, low habitation, and strict pilgrimage control are vital to maintain pristine conditions.

6. Zanskar River (Ladakh)

The Zanskar, a tributary of the Indus, is known for its breathtaking turquoise clarity. The harsh Himalayan climate, absence of agriculture, and minimal human settlements preserve its condition.

While no large-scale WQI survey exists, satellite imagery and field expeditions confirm extremely low turbidity and contamination levels (NDTV Travel, 2023).

Case Study:

The Zanskar Eco-Tourism Collective (2021) established “no-waste treks” along rafting routes. Tourists must carry back their waste ; a model of responsible adventure tourism.

7. Periyar River (Kerala: Upper Basin)

Though lower stretches near Kochi are polluted, the upper Periyar originating inside Periyar Tiger Reserve remains remarkably clean.

The reserve’s closed forest canopy prevents soil erosion and nutrient overload. Water monitoring by the Kerala State Pollution Control Board classifies this stretch under Class A standards for drinking water (KSPCB, 2023).

Case Study:

The Periyar Eco-Development Project integrates local communities in buffer-zone protection, balancing tourism income with catchment conservation.

8. Parvati River (Himachal Pradesh)

The Parvati River, flowing through Kullu’s scenic valley, is a tributary of the Beas.

Due to dense forest cover and low population density, its upper reaches remain clean and biologically rich.

Local youth groups organize annual “Clean Parvati Drive”, collecting plastic waste from trekking trails.

While hydropower projects downstream pose risks, upper Parvati remains among India’s most visually pristine rivers (NDTV, 2023).

Case Study:

NGOs like Sarthak Himachal have installed waste-collection points and bio-toilets near Kasol to prevent river contamination.

9. Ravi River (Himachal Pradesh / Punjab)

Originating in the Himalayas, the Ravi River maintains high-quality water in its upper stretches.

According to CPCB 2021 data, several Ravi sampling stations recorded BOD < 3 mg/L, indicating bathing-quality water (CPCB Report, 2021).

Case Study:

The Chamera Hydropower Project in Himachal has adopted eco-flow releases and sediment traps to minimize pollution downstream; setting a rare example of green hydropower integration.

10. Chalakudy River (Kerala)

The Chalakudy River, originating from the Western Ghats, is often described as Kerala’s cleanest river.A biodiversity assessment found 98 freshwater species, including 35 endemics ,clear evidence of good ecological health (Wikipedia ).

The river’s upper catchment benefits from strict land-use control, and the Athirappilly waterfalls segment remains virtually unpolluted.

Case Study:

Post the 2018 Kerala floods, community groups like River Research Centre (RRC) launched the “Chalakudy Puzha Samrakshana Samithi,” restoring riparian vegetation and monitoring pH/DO levels.

Common Success Factors & Challenges

What Makes Rivers Cleaner?

Across all ten case studies, the following can be seen as the success factors:

Remote or Forested Headwaters (Zanskar, Umngot, Teesta):

Most of India’s cleanest rivers begin in remote mountain or forested regions where human activity is limited. The Zanskar in Ladakh and Teesta in Sikkim rise from glacial sources, while the Umngot River flows through densely forested Meghalaya hills. These headwaters have natural filtration through rocks and vegetation, minimal agricultural runoff, and negligible sewage inflow resulting in low turbidity and high dissolved oxygen levels. In essence, geography itself becomes the first line of protection.

Protected Areas (Periyar, Chambal):

Rivers that flow through protected sanctuaries or tiger reserves benefit from strict conservation rules. The Periyar River inside the Periyar Tiger Reserve and the Chambal River inside the National Chambal Sanctuary remain clean because industrial discharge, fishing, and construction are legally restricted. This legal protection of riparian zones maintains both water quality and biodiversity. In these cases, ecological regulation doubles as effective pollution control.

Strong Community Participation (Mawlynnong, Chalakudy)

No river protection succeeds without people. The Khasi community of Mawlynnong in Meghalaya and the local residents of Chalakudy in Kerala show how grassroots stewardship can outperform formal enforcement. Villagers actively monitor littering, restrict chemical use, and organize cleanup drives. Their success proves that behavioral discipline and cultural pride are powerful tools in maintaining river health.

Low Population Density and Industrial Absence

All ten rivers share one striking feature; absence of heavy urban or industrial influence. Sparse settlements mean less sewage discharge, fewer agricultural chemicals, and no industrial effluents. For example, stretches of the Narmada and Ravi remain clean mainly because upstream regions are not heavily urbanized. In contrast, river segments that pass through industrial belts quickly lose water quality, highlighting how urban planning and zoning directly influence ecological integrity.

Cultural Respect for Rivers as Sacred Entities

From the Bhagirathi to the Narmada, India’s clean rivers often hold deep spiritual significance. Ritual respect translates into conservation ethics , locals hesitate to pollute what they consider sacred. Pilgrimage zones like Gangotri have strict waste rules, and many Himalayan monasteries and temples along riverbanks emphasize cleanliness as spiritual duty. This intangible but powerful sense of cultural responsibility sustains reverence-driven conservation practices.

Key Takeaway:

Clean rivers in India are not accidents of geography; they are outcomes of balanced ecosystems, protective laws, local participation, and cultural ethics. Each of these factors must inform future river restoration programs and national water-quality policy.

In essence, cleanliness is not accidental, it’s a function of policy protection, ecological resilience, and cultural stewardship.

Persistent Threats Even to the Cleanest Rivers

No river is completely safe. Even pristine rivers face new pressures:

- Tourism waste in Parvati and Umngot.

- Hydropower and flow alteration in Teesta, Ravi, and Narmada.

- Climate-induced glacial melt affecting Bhagirathi and Zanskar.

A 2025 study on Chambal near Kota found moderate pollution emerging from untreated drains (JSTR).

Implications for Policy & River Restoration

These findings highlight what India’s river policies must prioritize:

- Identify reference rivers like Umngot or Chalakudy as clean benchmarks.

- Replicate community-based conservation at a national scale.

- Mandate real-time WQI monitoring accessible to the public.

- Integrate ecological flow in dam licensing.

Programs like Namami Gange could be expanded into a “National Clean Rivers Mission”, targeting both polluted and pristine rivers (UNEP).

Future Outlook: Scaling Up Clean River Action

Setting Ambitious National Benchmarks

India could establish a Clean Rivers Index, ranking rivers annually based on DO, BOD, biodiversity, and community participation, similar to the EU Water Framework Directive model.

Publishing these rankings in the public domain would increase transparency and citizen accountability.

Technological and Community Innovations in River Monitoring

India’s approach to clean water is rapidly evolving. Traditional water testing, which depended on manual sampling and lab analysis, is being transformed by digital technologies and citizen participation. These innovations are making river monitoring more transparent, continuous, and actionable.

1. IoT-Based Water Sensors: Real-Time Monitoring for Smarter Action

The Internet of Things (IoT) is revolutionizing how India tracks water quality.

IoT-based river sensors, installed at strategic points along rivers such as the Ganga, Yamuna, and Sabarmati, continuously measure parameters like pH, turbidity, dissolved oxygen (DO), conductivity, and temperature.

According to the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG), more than 36 sensor stations have been deployed under the Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring Network (nmcg.nic.in). These devices transmit live data to centralized dashboards where scientists and pollution-control boards can detect contamination spikes instantly.

Unlike traditional manual testing , which can take days ; IoT networks provide minute-by-minute insights, enabling quick intervention when sewage or effluent levels rise.

IoT systems are also being tested by IIT-Kanpur and private startups such as FluxGen and Boson Whitewater, which are building low-cost, solar-powered sensors for rural water bodies.

2. Satellite-Based Turbidity Analysis: ISRO’s Bhuvan Portal

India’s space agency, ISRO, is playing an unexpected but vital role in river conservation. Through its Bhuvan Geo-portal, ISRO offers satellite-based turbidity and surface-water mapping tools that help scientists assess water clarity, algal blooms, and sediment transport across large basins.

The Bhuvan-NMCG portal specifically supports the Namami Gange programme, integrating satellite imagery from CartoSAT, Resourcesat, and Sentinel series satellites to map:

- Land use and encroachment along riverbanks

- Changes in water spread area and sediment load

- Erosion and flood-plain dynamics

Researchers use this data to identify where illegal sand mining or deforestation may be increasing turbidity. The system helps authorities prioritize cleanup projects and verify river-rejuvenation progress remotely

The integration of remote sensing with ground IoT sensors is expected to form a hybrid monitoring grid by 2030, giving India an unprecedented, continuous picture of river health.

3. Citizen “River Watch” Apps: Democratizing Water Stewardship

Technology is not just for scientists; it’s empowering citizens too.

Several mobile apps and citizen-science initiatives now let people participate directly in protecting rivers.

The “Bhuvan Clean Ganga App,” developed jointly by ISRO and NMCG, enables citizens to report illegal dumping, sewage discharge, or encroachment along riverbanks. Reports are geo-tagged and sent to district-level authorities for action.

Similarly, NGOs such as Earth5R and the Indian Rivers Forum have piloted “River Watch” programs, training volunteers to collect basic water-quality data using portable kits. These readings are uploaded to shared dashboards, creating community-driven water maps.

A growing number of youth groups in Kerala, Sikkim, and Himachal are also using WhatsApp-based “River Guardian” groups to crowdsource pollution alerts and cleanup campaigns.

These citizen apps are bridging the gap between public awareness and policy response ; proving that river stewardship thrives when data meets democracy.

The COVID-19 lockdown provided an accidental experiment; river health can recover quickly when pollution pressure is paused (BMC).

FAQs: From Umngot to Chalakudy: Inside India’s Cleanest Rivers and the Secrets to Their Survival

Which river is considered the cleanest in India?

The Umngot River in Meghalaya is widely recognized as India’s cleanest river. Its crystal-clear water, minimal industrial activity, and strict community waste rules in Dawki and Mawlynnong villages make it exceptionally pristine.

How is river cleanliness measured in India?

Cleanliness is measured using scientific indicators like Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), pH levels, and the Water Quality Index (WQI). A WQI score below 50 usually denotes clean or good-quality water.

What are the top ten cleanest rivers in India today?

Umngot (Meghalaya), Chambal (Madhya Pradesh–Rajasthan), Teesta (Sikkim–West Bengal), Narmada (Madhya Pradesh–Gujarat), Bhagirathi (Uttarakhand), Zanskar (Ladakh), Periyar (Kerala upper basin), Parvati (Himachal Pradesh), Ravi (Himachal–Punjab), and Chalakudy (Kerala) are currently among India’s cleanest rivers based on CPCB data, research studies, and environmental assessments.

Why is the Umngot River in Meghalaya so clean?

The Umngot River’s cleanliness comes from strong community stewardship, zero-industrial presence, and eco-friendly tourism rules enforced by local Khasi villagers who prohibit littering and direct waste disposal.

What makes the Chambal River different from others?

The Chambal flows through a protected wildlife sanctuary and has minimal industrial pollution. Its habitat supports endangered species like the gharial and river dolphins, indicating high ecological quality.

Is the Ganga River part of this list?

Only the Bhagirathi, an upper tributary of the Ganga, qualifies. The upper reaches near Gangotri and Uttarkashi remain clean, while the downstream Ganga suffers from urban and industrial pollution.

How clean is the Narmada River today?

Recent studies using the Fuzzy Water Quality Index (FWQI) show that several Narmada stretches meet Class B (bathing-quality) standards, thanks to sewage treatment initiatives and community audits along its ghats.

Which rivers in southern India are considered clean?

The Chalakudy River and the upper Periyar in Kerala are among the cleanest. Their sources lie in forested Western Ghats zones, and community conservation has helped preserve their clarity.

Does tourism help or harm river cleanliness?

Tourism can help when regulated but harms when unmanaged. For example, community-led ecotourism in Umngot supports conservation, while overtourism in Parvati Valley threatens water quality through waste and plastic litter.

Are there government policies protecting clean rivers?

Yes, initiatives like Namami Gange, National Chambal Sanctuary, and Periyar Eco-Development Project aim to maintain or improve water quality. The CPCB also conducts regular monitoring under the National Water Quality Programme (NWQP).

How does the Water Quality Index (WQI) help identify clean rivers?

WQI condenses multiple parameters such as BOD, DO, pH, turbidity into a single score. A lower WQI means cleaner water. This helps scientists and policymakers rank rivers and target interventions effectively.

What are the main threats to India’s clean rivers?

Emerging threats include unregulated tourism, hydropower development, sand mining, agricultural runoff, and climate-induced glacier melt, especially in Himalayan regions like Teesta and Bhagirathi.

What role do local communities play in river conservation?

Local communities are critical guardians. From the Khasi tribes protecting Umngot to Kerala’s river protection samitis, citizen-led models have proven more effective than top-down enforcement in many cases.

Has India’s river quality improved in recent years?

Yes, marginally. CPCB data shows polluted river stretches decreased from 351 in 2018 to 311 in 2022. However, only a few rivers like Chambal, Narmada, and Bhagirathi consistently meet high-quality benchmarks.

Why are Himalayan rivers often cleaner?

Himalayan rivers like Teesta, Zanskar, and Bhagirathi originate from glacial sources, flow through low-density areas, and have strong natural self-purification due to fast currents and cold temperatures.

Can India develop a Clean Rivers Index?

Experts recommend it. A “Clean Rivers Index,” modeled on the EU Water Framework Directive, could rank rivers based on pollution levels, biodiversity, and public participation , encouraging accountability and public awareness.

What was the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on river quality?

During lockdowns, several Indian rivers saw dramatic improvements. The Bhagirathi and upper Ganga showed up to 93% improvement in water parameters, highlighting how reduced human activity can rapidly restore river ecosystems.

Are any urban rivers in India considered clean?

Currently, no major urban river qualifies as “clean.” However, stretches of the Sabarmati Riverfront and Ganga at Haridwar have shown periodic improvements due to treated water inflow and stricter waste regulation.

What lessons can policymakers learn from India’s clean rivers?

Policy should focus on catchment conservation, decentralised waste treatment, ecological flow maintenance, and empowering communities as co-managers of river ecosystems rather than treating rivers only as resources.

How can individuals contribute to keeping rivers clean?

Avoid dumping waste, minimize use of chemical detergents, participate in local cleanup drives, and support ecotourism initiatives. Clean rivers start with clean habits such as collective action is key to sustaining India’s waterways.

From Admiration to Action: Keeping India’s Rivers Alive

India’s cleanest rivers from the glassy Umngot to the serene Chalakudy — show us what is possible when nature, people, and policy work together. But their purity is not guaranteed. Every year, rising tourism, plastic waste, and unplanned development threaten these fragile ecosystems.

It’s time to turn admiration into action.

Each reader, traveler, and policymaker has a role to play:

- Respect rivers as living ecosystems, not waste channels.

- Refuse plastic and chemical pollution near riverbanks.

- Join or support local clean-river drives; even small efforts multiply.

- Hold authorities accountable for untreated sewage and illegal dumping.

- Share success stories like Umngot or Chambal to inspire replication nationwide.

The journey from “polluted” to “pristine” is not beyond reach; these ten rivers are proof. If India can protect its cleanest waters today, it can revive its dying ones tomorrow.

Our rivers reflect who we are.

The clearer they run, the stronger our nation’s commitment to sustainability, culture, and collective care.

Let this not be a story of ten exceptions; let it be the beginning of a national movement for clean rivers, where every stream becomes a symbol of renewal and responsibility.

Authored by- Sneha Reji