A Nation Drowning in Waste

India’s waste problem is no longer remote; it’s at our doorstep. With millions of tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) generated every day, the country is facing a human-made crisis of scale, urgency and consequence.

According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), average daily solid waste generation in India reached 170,338 tonnes per day (TPD) in 2021-22. Despite this, only about 91,512 TPD of that was formally treated.

Rapid urbanisation, rising consumption, and a shift in lifestyle mean that this waste generation is only set to increase. One study forecasts total urban MSW in India climbing from 62 million tonnes in 2015 to as high as 165 million tonnes by 2030 ; a near three-fold rise.

This crisis isn’t just about the piles of garbage. It’s about choking landfills, polluted rivers, methane emissions, public health risks and lost economic opportunity. It challenges cities, central and local governments, businesses, and citizens alike.

In that context, the work of Earth5R stands out: identifying cities that are “breaking the pattern”, offering replicable strategies in the Indian context. This article maps the scale of India’s waste challenge, explains where and why the system is failing, presents seven case-study cities that are turning the tide, and draws out policy lessons for the decades ahead.

Let’s begin by diving into the scale of the problem.

The Scale of the Crisis: India’s Waste Problem in Numbers

India’s waste story starts with the numbers,and they are hard to ignore.

How Much Waste India Really Generates Today

According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), India generated an average of 170,338 tonnes per day (TPD) of municipal solid waste in 2021-22; of this, only 91,512 TPD was treated. Earlier research estimated urban India produced around 62 million tonnes (Mt) of solid waste around 2015, roughly 450 grams per person per day. ResearchGate The International Trade Administration notes that national MSW generation could rise to 165 Mt by 2030 unless strong interventions are taken. Trade.gov These figures show a steep upward trajectory: more people in cities, more consumption, more waste.

Where the Waste Actually Goes?

Collection and treatment are massive bottlenecks. One study reveals that in Indian cities circa 2015, only about 28% of collected waste was treated, and the remaining 72% was openly dumped. ResearchGate The CPCB 2020-21 report cites ~282 TPD generation, but only 108.6 TPD treated (as per one excerpt) though values differ across sources. Central Pollution Control Board A recent working paper (EAC-PM) states that about 160,039 TPD was generated in 2020-21, highlighting ongoing high volumes. eacpm.gov.in Further complicating the picture: per-capita waste generation in Indian cities varies by size, often between 0.3 to 0.6 kg/day, with larger metros producing nearer to 0.5 kg/day or more. ResearchGate Clearly, generating the waste is only half the battle processing and disposal lag far behind.

The Invisible Cost of Inaction

The consequences of failing to manage this volume are wide-ranging:

- Public health: Open dumping and burning of waste creates conditions for vector-borne disease, respiratory ailments, and contamination of water and soil.

- Climate & environment: Decomposing waste in landfills emits methane;a potent greenhouse gas. A literature review shows India’s per-capita waste generation (around 370 g/day) is part of a broader global link between waste and GDP growth. PMC

- Economy: When waste isn’t processed, it imposes costson land value, on cleanup, on health systems, on lost materials (that could have been recycled).

- Urban infrastructure: Many cities lack enough landfill space, waste transport systems, or processing plants creating pressure points in urban planning.

In short: The volume of waste, its rapid growth, combined with weak processing, creates a crisis of management, not just generation.

Why the System is Failing: Core Structural Gaps

India’s waste crisis is not only about volume. It is about weak systems that cannot keep pace with cities and consumption. The gaps are structural and persistent. They show up at every stage from a household bin to a landfill slope.

Segregation Breaks Down at the Source

Most Indian cities still struggle to keep wet and dry waste apart. That failure multiplies downstream problems. When organics mix with plastics, recycling drops and dumpsites emit more methane. National cleanliness surveys have pushed segregation as a key metric, but practice lags policy in many cities. MoHUA’s Swachh Survekshan framework increased weightage for source segregation and for cutting dumpsite inflows, yet implementation remains uneven across states and city sizes. Press Information Bureau

The data story is clear. India generated about 170,338 tonnes per day (TPD) of municipal solid waste in 2021–22. Only 91,512 TPD was treated. The rest was landfilled, dumped, or left unmanaged, which signals that segregation and processing do not yet match generation. Press Information Bureau

Municipal Capacity and Finance Do Not Match the Mandate

Urban local bodies are responsible for daily collection, transport, processing, and legacy waste remediation. Many do not have the funds, staff, or planning tools to do all four well and at scale. Earlier government analyses flagged low per-capita municipal spending and thin revenue bases, which hamper basic services like waste management. These structural finance gaps have persisted, even as waste volumes and complexity rise. Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs

A 2024 working paper for the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM) underscores the core challenge: rapid urbanisation has outpaced system capacity, leaving a chronic treatment deficit and heavy reliance on landfills. The paper calls out the need for better planning, stronger contracts, and measurable performance outcomes. eacpm.gov.in

Landfill Dependence Creates Environmental and Safety Risks

Open dumping and overfilled landfills remain common in fast-growing cities. Delhi’s Ghazipur site illustrates the risk. A 2024 Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) report to the National Green Tribunal noted a current height of about 65 metres and tens of millions of tonnes of legacy waste, with daily inflows continuing. This scale makes fire control, leachate, and slope stability constant concerns. Green Tribunal

This is not only a local issue. Global data show that open dumping and poorly managed landfills still handle a large share of waste in low- and middle-income countries, increasing air and climate risks. Inadequate disposal is associated with higher methane emissions and frequent fires, especially where organic fractions are large and segregation is weak. Data Topics

Plastic Waste and Patchy EPR Execution

India has tightened plastic rules and adopted Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for plastic packaging. The 2022 guidelines created an online EPR portal and clearer targets for producers, importers, and brand owners. These reforms are important, but enforcement and last-mile collection remain uneven, particularly for low-value and multi-layered plastics that often escape formal systems. Cities still report leakage into drains, water bodies, and mixed waste streams. Central Pollution Control Board

The challenge is circularity at scale. Without strong segregation, traceability, and buy-back markets, even good EPR frameworks struggle to lift recovery rates for hard-to-recycle plastics. That is why city systems and producer systems must align; on data, contracts, and accountability.

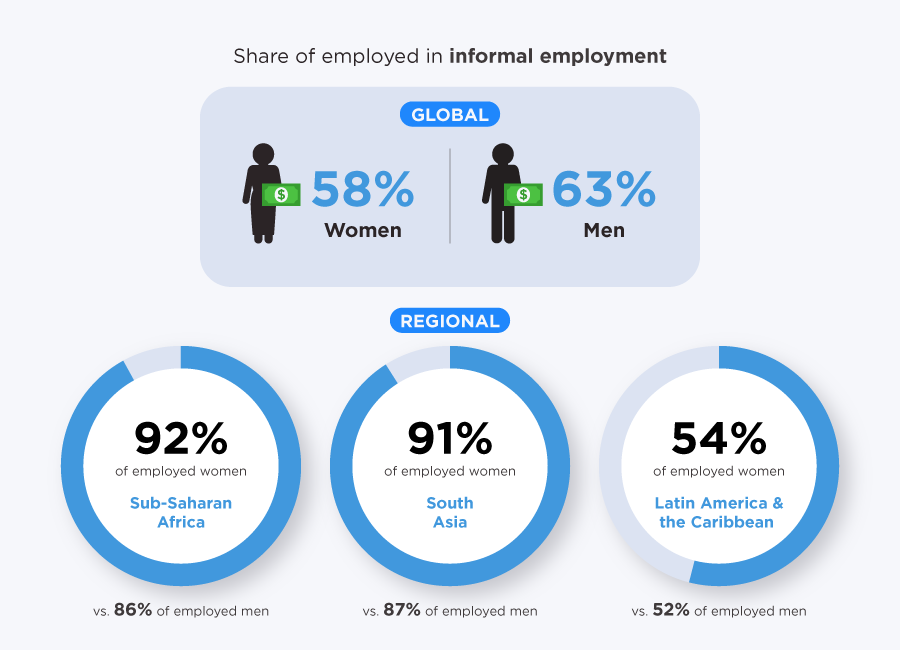

The Informal Workforce Remains Under-Recognised

Waste pickers and itinerant buyers are central to India’s recycling economy. Estimates suggest 1.5–4 million people work in this informal ecosystem nationwide, recovering recyclables that the formal system often misses. Where cities partner with organised waste picker groups, recovery rates improve and costs fall. Bengaluru’s experience shows measurable savings to the municipality when informal workers are integrated into service models. Yet, in many cities, workers still lack ID cards, social protection, and secure livelihoods. hasirudala.in

Bringing this workforce into formal value chains is not only fair. It is efficient. It lifts material recovery, reduces landfill pressure, and supports safer working conditions.

Missing Links in the Circular Economy

India’s rules recognise composting, biomethanation, material recovery facilities (MRFs), and EPR. But cities still invest more in hauling mixed waste than in decentralised processing and high-quality MRFs. When organics are stabilised near the source and dry fractions reach clean MRF lines, transport drops, emissions fall, and recycling markets improve. The EAC-PM paper argues for data-driven planning and capacity that matches city scale; ward-level composting where feasible, reliable contracts for dry waste sorting, and performance-linked payments. eacpm.gov.in

The World Bank’s global evidence points the same way: cities that shift from dumpsites to sanitary systems, and from mixed collection to segregation with local treatment, see better environmental and fiscal outcomes over time. Technology helps, but governance, funding, and accountability matter more. World Bank

The bottom line: India’s waste crisis is a system crisis. Segregation fails at the doorstep. Municipal finance and capacity fall short of mandates. Landfills dominate disposal, raising risk and cost. Plastics test EPR enforcement. And the informal sector remains under-used in official plans. Fixing these gaps is the bridge between policy intent and cleaner streets.

7 Indian Cities Leading the Waste Revolution: How Local Innovation Is Redefining Urban Sustainability

Lets move to the seven Indian cities that are active models of change in waste management, each offering evidence of systemic improvement. These case studies illustrate how targeted actions, strong governance and citizen engagement can shift outcomes.

1. Indore (Madhya Pradesh): From Mess to Model City

Indore, often ranked India’s cleanest city, has transformed its waste management system dramatically. It has achieved universal door-to-door collection, strict source segregation, and effectively zero legacy dumpsites. Smart City

Key features:

- India’s first PPP-based green-waste processing plant launched in 2025, targeting wood and branch waste, converting it into pellets and thereby adding revenue streams to the municipal model. The New Indian Express

- Waste generation estimated at 1,115 metric tonnes per day (MTPD) in earlier reports, with an organised system across 85 wards and 19 zones. Smart City Indore

- Clear leadership commitment and citizen engagement have helped Indore discard the ‘trash city’ label and become a benchmark for circular economy practices. Clean India Journal

2. Ambikapur (Chhattisgarh): Women-Led Waste Revolution

Ambikapur provides a striking example of how community and gender-inclusive approaches can reframe waste management.

- The city engages hundreds of women through self-help groups (SHGs) in everyday tasks such as collection, segregation and sorting of waste. One report notes 470 women actively working in the system. Mongabay-India

- It pursues a decentralised chain from collection to processing, reducing reliance on central dumpsites. UNCRD

- Key results: Ambikapur generates 51.5 tonnes of waste daily, of which 35.7 tonnes were organic and diverted into composting and processing. The Times of India

3. Pune (Maharashtra): Cooperative First, Landfill Later

Pune has evolved a technically and socially integrated model of waste management anchored in informal-sector empowerment.

- The cooperative SWaCH (Solid Waste Collection & Handling cooperative) is owned by waste pickers and partners with the municipal corporation to provide door-to-door services to 80% of households in its domain. World Resources Institute

- Research shows the SWaCH model is cost-effective and replicable, combining labour-intensive collection with high recovery rates of recyclables. ResearchGate

- The model builds sustainable livelihoods, giving waste pickers ownership and social security, and aligns waste diversion with social equity.

4. Alappuzha (Kerala): Small Town, Big Gains via Decentralisation

Alappuzha offers a compelling case of how small-city scale allows rapid adoption of decentralised waste systems.

- According to the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), all 52 wards of Alappuzha practice source segregation; the city has no formal landfill. cseindia.org

- As early as 2016-17, the city was recognised by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) for its sustainable waste practices. Down To Earth

- Model features: local composting, micro-processing units close to point of generation, minimal transport. The tagline: “Ente malinyam, ente utharavathithwam” (My garbage, my responsibility). The News Minute

5. Mysuru (Karnataka): Urban Planning Meets Waste Segregation

Mysuru stands out for embedding waste practices into city planning frameworks.

- Independent studies highlight that Mysuru generates 259 tonnes of MSW per day and has initiated integrated Solid Waste Management plans. Scribd

- Though not perfect, the city has progressed with strategies such as multi-stream segregation and ward-level composting units that reduce the load on central disposal sites. Earth5R

- Example: With persistent efforts, Mysuru’s door-to-door collection plus segregation helped reduce landfill waste by ~30% in one analysis. Earth5R

6. Panaji (Goa): A Tourism-Linked Waste Strategy

Panaji’s is a village of small size with high tourist traffic, demands waste strategies that align with sustainability and cleanliness for both residents and visitors.

- The city links its waste management goals with tourism regulation, home composting, and strong plastic waste enforcement – making municipal systems sensitive to visitor flows and resident habits.

- While specific day-by-day tonnes are less publicly documented, Panaji’s participation in national cleanliness rankings and its inclusion in the “clean cities” category underscore that a tourism-aware waste management approach is practical and scalable in similar cities.

7. Bengaluru (Karnataka): Citizen-Driven Decentralised System in a Mega-City

In India’s tech-forward metro context, Bengaluru offers insights on how citizen activism, decentralised processing and informal sector integration can align at scale.

- Bengaluru launched the “2-bin & 1-bag” system: households separate wet and dry waste into two bins, and one extra bag for plants/flowers etc. This simplified messaging aids adoption.

- The city has deployed over 200 decentralised composting/biomethanation units within its urban environment, shortening transport and supporting local processing.

- Organisations like Hasiru Dala (a waste picker collective) work alongside the municipal body to formalise informal recycling pathways.

- While full data on diversion rates is evolving, the city represents a promising shift away from “haul-to-landfill” models in mega-cities.

Why These Cities Stand Out

Across these seven, certain common factors emerge:

- Reliable door-to-door collection and source segregation.

- Decentralised processing (compost, biomethanation, MRFs) rather than reliance solely on large landfills.

- Formal inclusion of waste pickers or cooperatives in collection/recycling chains.

- Strong citizen engagement and behaviour change programmes.

- Proactive municipal leadership and willingness to treat waste as a resource not simply a burden.

Together, they illustrate that India’s waste crisis is not inevitable. With policy alignment, community buy-in and operational clarity, cities can begin breaking the pattern.

What These 7 Cities Did Differently: Key Lessons for India

The seven cities featured in the Earth5R analysis do not succeed because they are richer, newer, or technologically superior. They succeed because they changed the rules of the system, not just the tools. Their strategies offer a blueprint for cities across India, regardless of size or budget.

1. Policy Enforcement and Citizen Participation Worked Together

In Indore, Pune, and Bengaluru, the biggest shift was not infrastructure; it was behaviour change backed by enforceable rules.

Indore’s success came after strict fines on non-segregation, public dashboards on ward-level performance, and sustained citizen outreach campaigns led by the municipal commissioner. Official records show Indore has maintained 100% door-to-door collection and segregation for multiple consecutive years, verified by Swachh Survekshan audits.

This combination rules with awareness and monitoring created consistency, not one-time cleanups.

2. Decentralised Waste Management Over Centralised Landfills

Alappuzha, Mysuru, and Bengaluru proved that processing waste near the point of generation reduces transport cost, emissions, and landfill dependency.

Alappuzha has no central dumpsite. Every ward handles its own organic waste through composting or biogas plants.

Bengaluru has 200+ decentralised biomethanation and composting units, cutting long-distance hauling of wet waste.

Ambikapur runs 48 decentralised sorting centres managed by women’s self-help groups, reducing transport by 70%.

The lesson: Waste becomes unmanageable only when it travels too far.

3. Waste Pickers Were Not Removed , They Were Formalised

Pune and Bengaluru shifted the narrative: informal workers were not a “problem”, they were the missing workforce in a circular economy.

Pune’s SWaCH cooperative; India’s first of its kind allowed 3,500+ waste pickers to become paid service providers under municipal contract.This increased recycling rates, reduced landfill dependency, and saved the municipal body millions in labour cost.

Evidence from WIEGO shows formalising waste pickers reduced PMC’s solid-waste handling cost by over ₹5 crore annually.

The takeaway: Inclusion is not charity; it is efficiency.

4. Organic Waste Was Treated as a Resource, Not “Garbage”

Nearly 50–60% of India’s municipal waste is biodegradable. Cities that diverted this fraction saw the fastest transformation.

Indore converts wet waste into compost and compressed biogas (CBG).

Bengaluru runs ward-level biomethanation plants producing gas for civic kitchens.

Alappuzha’s “pipe composting” model turned kitchen waste into garden fertiliser without trucks or landfills.

Result: less methane, less leachate, less transport, and new income streams for city budgets.

5. Data and Accountability Were Treated as Core Infrastructure

Indore uses a GPS-tracked fleet, QR-coded bins, and ward rankings to maintain transparency.

Pune publishes user-fee records and waste-picker rosters online.

Ambikapur tracks household-level segregation via SHG-led route auditing.

This reflects a consistent pattern:

“What gets measured gets managed. What stays invisible stays ignored.”

Cities that track waste flows perform better than cities that only buy new machinery.

The Shared Takeaway

They acted at household level (segregation, user-fees, fines)

They processed waste close to where it was generated

They treated waste pickers as workers, not beneficiaries

They reduced landfill dependence instead of expanding it

They aligned policy, citizen action, and local economy

In other words:

India doesn’t need more landfills. It needs more Indores, Punes, Alappuzhas, and Ambikapurs.

Earth5R’s Model for a Zero-Waste Future

India’s waste crisis is not only a governance challenge; it’s a design challenge. Earth5R approaches it by reframing waste as a local economic resource, not a disposal problem. Its model combines circular economy principles, social inclusion, and data-driven execution. The goal: make waste prevention, recovery, and reuse financially viable, socially fair, and environmentally restorative.

1. Circular Economy Projects Built at Community Scale

Earth5R does not start with machinery. It starts with material flow mapping; what waste is generated, in what quantity, and where it leaks.

Once mapped, each neighbourhood is treated as a micro-economy:

- Organic waste: compost, biogas, bio-enzymes

- Dry waste: recycled plastics, upcycled textiles, eco-bricks

- High-value recyclables: tied to formal MSME or scrap markets

The model borrows from the logic visible in Indore, Pune and Alappuzha:

“The closer waste stays to the source, the higher the chance it becomes a resource.”

Earth5R has implemented such systems in India, France, Switzerland, and Latin America; proving the model is adaptable beyond geography.

2. CSR and ESG Waste Intervention Model

Corporations in India generate and finance large waste streams. Earth5R links them to local governments and communities via impact-tracked CSR projects, such as:

- Plastic offset programmes

- Village-level composting units

- School and campus segregation systems

- Employment of informal workers under ESG funds

This aligns with India’s mandatory CSR law and global ESG reporting standards that now require metrics on circularity, material recovery, and carbon savings.

Such models also ensure that waste funding is not charity-driven but compliance-driven and audit-backed.

3. Social Inclusion: Waste Pickers as Climate Workforce

Earth5R treats informal waste workers as frontline climate actors.

They are trained, certified, and brought into value chains as:

- Collection partners

- MRF operators

- Upcycling entrepreneurs

- Plastic credit verifiers

This echoes the SWaCH (Pune) and Hasiru Dala (Bengaluru) models, where formalisation increased recycling rates and municipal savings.

The organisation argues that India cannot meet SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption & Production) or Paris climate targets without integrating informal labour into the circular economy.

4. Digital Tools: Waste Mapping, Carbon Metrics, and Impact Analytics

Earth5R runs a digital platform that allows:

- Geotagged waste audits

- Carbon impact tracking per project

- Material value chain tracing

- Integration of CSR reporting dashboards

This is crucial because most waste systems fail not due to lack of effort but due to lack of traceable, verifiable data.

The platform creates accountability between citizens, corporations, and municipalities.

5. The “Zero-Waste City Framework”

Earth5R’s city-level strategy works in 5 stages:

- Baseline Waste Audit: tonnage, composition, leak points

- Decentralised Processing Setup: compost units, MRFs, biogas

- Circular Economy Training: households, schools, vendors

- Social Integration : waste picker formalisation, livelihood mapping

- Long-Term Accountability System: policy and data and financial model

This framework is not hypothetical; it is based on field learnings from 50+ cities and 12 countries, combined with Indian waste policy alignment (SWM Rules 2016, Plastic Rules 2022).

The Core Idea

“Waste is not a disposal problem but a resource-flow problem.

Fix the flow and you fix the landfill, the economy, and the climate burden.”

Earth5R’s model proves that India can move from waste management to resource management; if the system is redesigned around people, policy, and data.

The Policy Shift India Needs Now

India has the rules. It needs sharper execution. The next decade should focus on source segregation, producer accountability, workforce inclusion, landfill exit plans, and municipal finance; all backed by transparent data.

Mandatory segregation, with real enforcement

India’s Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules, 2016 require every waste generator to segregate waste at source into biodegradable, non-biodegradable, and domestic hazardous streams. They also put clear duties on local bodies for door-to-door collection, processing, and scientific disposal. Cities should move from “advisory” to measurable compliance, with ward-level audits and proportionate penalties for chronic non-segregation. Central Pollution Control Board

Enforcement is not about punitive action alone. It works when paired with service reliability (daily, segregated pickup) and simple citizen cues. City contracts should pay service providers for segregated tonnes collected and processed, not just kilometres hauled. This aligns incentives with the Rules’ intent.

Close the plastic loop: EPR that bites

The Plastic Waste Management framework including the 2022 amendments and detailed Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Guidelines spells out targets for producers, importers, and brand owners, and runs on a national online portal. Now the task is tightening verification, traceability, and third-party audits, especially for low-value and multi-layer plastics that keep leaking into drains and mixed waste. Cities should integrate their MRF data with the CPCB EPR portal so recovered plastic flows are visible and creditable. Central Pollution Control Board+2Central Pollution Control Board

Clear public reporting—by material type and by ward will show if EPR is reducing municipal burden or merely shifting paperwork. Global evidence is unambiguous: better segregation and producer take-back lower methane and open dumping. Data Topics

Recognise waste pickers in law and contracts

Informal recyclers recover value the formal system misses. Cities that contract with cooperatives or register waste pickers raise recovery and cut costs. A national template for waste-picker integration; ID cards, social protection, standard service fees, and priority access to dry waste would unlock scale beyond pioneering cities like Pune and Bengaluru. Embed these terms in municipal bye-laws and concession agreements. World Bank

When workers are recognised, material stays clean, diversion rises, and landfill pressure eases. It is a climate policy, a social policy, and a fiscal policy rolled into one.

A time-bound exit from landfills

Open dumps and over-topped landfills are environmental and safety risks. The NGT-monitored record for Delhi’s Ghazipur shows the scale: a mound about 65 metres high and 8.2 million tonnes of legacy waste, with daily inflows still occurring. Any credible national plan must set dated milestones for (1) stopping fresh dumping, (2) biomining legacy waste, (3) building sanitary capacity only as a transition, and (4) verifiably capping closed cells with leachate and gas management. Green Tribunal

State pollution control boards should publish quarterly, site-level dashboards: tonnes incoming, tonnes biomined, fires, leachate handled, gas captured, and public complaints resolved. This brings landfill exit pathways into public view and policy accountability.

Fund the mandate: stable money for ULBs

Mandates without money stall. The 15th Finance Commission set aside ₹1.2 lakh crore for urban local bodies over 2021–26, part of ₹4.36 lakh crore to local governments overall, with performance-linked components. Tie a portion of tied grants to segregation rates, processing capacity actually used, and landfill diversion achieved, not just assets created. Release tranches against audited outcomes, not DPRs. PRS Legislative Research

On the ground, the Union Finance Ministry has released tied grants for ULBs (including for sanitation and SWM). States should pass these funds through quickly and protect them from ad-hoc cuts, so cities can sustain services and pay community partners on time. Press Information Bureau

Data transparency as core infrastructure

What gets measured gets managed. Require every million-plus city to maintain a public waste dashboard: daily tonnes by stream, collection coverage, processing utilisation, rejected residues, landfill inflows, emissions estimates, and EPR credits reconciled. The EAC-PM working paper highlights an enduring treatment deficit and calls for data-driven planning. Make that operational by standardising metrics and publishing them monthly. eacpm.gov.in

Decentralise by design

India’s rules already recognise composting, biomethanation, and MRFs. Codify ward-level capacity norms, for example, cities above a threshold must ensure enough decentralised organic processing within a 3–5 km radius of generation. This trims haulage costs, curbs fires at dumps, and stabilises recycling markets. The World Bank’s What a Waste 2.0 points to these benefits when cities move from mixed haul-and-dump to segregation with local treatment. Data Topics

Align contracts with climate outcomes

Procurement should reward tonnes diverted and methane avoided, not just plant installation. Include pay-for-performance and open-book costing so city engineers and citizens can see whether facilities are operating at design capacity. Link waste-to-energy or biomethanation to feedstock quality standards; no plant should be paid to burn wet mixed waste.

The Next Decade: Two Possible Futures for India’s Waste Story

ndia’s waste journey can move in two very different directions. The next decade will decide whether the country leads the global circular economy transition or becomes overwhelmed by its own waste footprint.

Future 1: If India Adopts the 7-City Model

In this future, India scales the proven strategies seen in Indore, Ambikapur, Pune, Alappuzha, Mysuru, Panaji and Bengaluru ; segregation at source, decentralised processing, waste-picker inclusion, and data-linked accountability.

If that happens, verified outcomes from existing cities suggest India could achieve:

- Massive landfill reduction: Cities that segregate and compost locally cut landfill inflow by 60–80% (based on Indore, Alappuzha, Ambikapur field data).

- Lower methane emissions: Since 50–60% of Indian waste is organic, treating it through composting/biogas can prevent landfill methane; a high-impact climate action recognised by the IPCC.

- Stronger circular economy: India’s recycling market (already worth ₹1.2 lakh crore+) expands with better material recovery and formalised recycling chains.

- Lower municipal spending: Pune’s SWaCH model alone saves over ₹5 crore per year in labour and dumping costs by integrating waste pickers.

- Behaviour change becomes normal: Cities like Indore and Mysuru show that once segregation becomes routine, compliance stays high.

- CSR and ESG investments flow in: Companies can meet plastic, carbon and circularity mandates by funding waste-to-resource projects instead of just “clean-up drives.”

In this pathway, India does not need more dumping grounds; it needs local processing, real enforcement, and people-centred systems.

Future 2: If Business-as-Usual Continues

If segregation remains optional, landfills keep growing, and EPR stays on paper, India faces a multi-layered crisis driven by unmanaged waste.

Based on official projections and current trajectories:

- Total waste shoots past 165 million tonnes per year by 2030 (World Bank, ITA estimates).

- Landfills turn into permanent garbage mountains, like Ghazipur — over 65 metres high, taller than many buildings.

- Waste becomes one of India’s top methane sources, worsening heatwaves and smog.

- Public health risks multiply: toxic fires, mosquito breeding, microplastic contamination, respiratory illnesses.

- Economic losses soar: clogged drains cause urban floods, polluted land reduces property value, and health impacts strain public systems.

- Legal pressure rises: NGT and courts continue to intervene as civic anger grows over landfill fires and failed collection systems.

In this scenario, waste stops being a “municipal issue” and becomes a national environmental, economic and health crisis.

What Determines Which Future India Gets?

Not new technology. Not foreign funding.

Three proven decisions already visible inside India:

- Make segregation compulsory and actually enforce it.

- Recognise and integrate waste pickers as part of the formal system.

- Stop sending mixed waste to landfills permanently.

The future is not about finding new solutions.

It is about replicating the ones already working.

Waste Is Not a Problem, It’s an Untapped Resource

India’s waste crisis is real, escalating, and urgent but it is also solvable. The evidence is already visible inside the country, not outside it. Seven cities have shown that waste is not an inevitable burden of urbanisation; it is a design failure that can be reversed with the right mix of policy, participation, and accountability.

What Indore, Ambikapur, Pune, Alappuzha, Mysuru, Panaji, and Bengaluru prove is simple:

The problem is not waste.

The problem is treating waste as waste, instead of as a resource stream.

Where cities treat organic waste as compost or biogas, landfills shrink.

Where informal workers are treated as partners, not invisible labour, recycling rates jump.

Where rules are enforced and data is public, citizens comply and systems stabilise.

India does not need to wait for imported technology, billion-dollar incinerators, or futuristic smart bins.

It needs what is already working scaled, funded, and enforced.

FAQs: India’s Waste Crisis and the Cities Breaking the Pattern : An Earth5R Analysis

What is the biggest reason India’s waste crisis keeps growing?

The core issue is not waste generation alone, but the lack of segregation at source. When wet and dry waste are mixed, recycling collapses, landfills overflow, and methane emissions rise.

How much waste does India generate every day?

According to the Central Pollution Control Board, India generates over 170,000 tonnes of municipal solid waste per day, and a large share of it still ends up in landfills.

Why is source segregation so important?

Segregation determines whether waste becomes a resource or a liability. Once organic waste mixes with plastic and hazardous waste, recovery becomes expensive and inefficient.

What percentage of India’s waste is organic?

Roughly 50–60% of India’s municipal solid waste is biodegradable, which means it can be composted or converted into biogas instead of being dumped.

Why are Indian landfills dangerous?

Most are open dumps rather than scientific landfills. They emit methane, catch fire, pollute groundwater, and release toxic fumes. Sites like Ghazipur in Delhi are taller than 20-storey buildings.

What is the circular economy approach to waste?

Instead of dumping or burning materials, the circular economy keeps them in use through repair, reuse, recycling, composting, and industrial recovery, creating jobs instead of pollution.

Which Indian city is considered the cleanest?

Indore has held the title of India’s cleanest city for several years due to 100% door-to-door collection, strict segregation rules, and zero unmanaged landfill dumping.

How did Ambikapur become a national model?

The city turned waste management into a women-led livelihood system, with self-help groups running decentralised sorting centres and earning from recyclables and compost.

What makes Pune’s model unique?

Pune formally integrated waste pickers through the SWaCH cooperative, proving that social inclusion and cost-effective recycling can go together.

How does Alappuzha manage waste without a landfill?

The city adopted full decentralisation. Every ward processes its own organic waste through composting units, so almost nothing needs to be transported or dumped.

Why is Bengaluru considered a decentralised waste pioneer?

The “2-bin, 1-bag” system, decentralised biomethanation plants, and partnerships with waste picker groups like Hasiru Dala have allowed the city to reduce landfill dependence.

What is EPR in waste management?

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) makes companies responsible for collecting and recycling the packaging waste they put into the market, especially plastics.

Can waste really be turned into energy or fuel?

Yes, organic waste can turn into biogas or CBG (compressed biogas), and clean dry waste can be converted into RDF (refuse-derived fuel). But it only works if waste is segregated first.

Why is the informal sector critical for India’s recycling system?

An estimated 1.5–4 million waste pickers recover materials the formal system would otherwise lose. Without them, recycling rates would drop sharply.

Are waste-to-energy incinerator plants the solution?

They are only efficient when waste is dry and segregated. Burning mixed, wet waste leads to toxic emissions, high costs, and poor energy output; a common failure in Indian cities.

What is the biggest policy gap in Indian waste management?

Implementation. India has strong rules (SWM Rules 2016, Plastic Rules 2022), but enforcement, funding, and monitoring are inconsistent across states and cities.

How can ordinary citizens help?

Segregate waste at home, compost organic waste, reduce single-use plastics, and support local recycling or zero-waste initiatives. Behaviour change is the first step in every successful city.

What role does CSR or ESG funding play in waste solutions?

Companies can fund waste processing infrastructure, plastic recovery programmes, and waste picker formalisation all of which also count toward ESG and sustainability reporting.

Is zero-waste possible in Indian cities?

Yes, but only through decentralisation, strict segregation, inclusion of informal workers, and transparent data tracking, as shown by Alappuzha, Indore, and Ambikapur.

What will decide India’s waste future technology or policy?

Policy and enforcement matter more than technology. Segregation, accountability, funding, and citizen compliance have transformed cities faster than machines ever did.

The Future of India’s Waste System Starts With Us

India does not need to wait for new technology, new laws, or new funding to solve its waste crisis. The solutions are already working in seven cities. The question now is whether we replicate them or keep repeating the landfill cycle.

If you are a citizen, start with segregation and refuse single-use plastics.

If you are a municipal leader, make decentralised processing and data tracking non-negotiable.

If you are a corporate or ESG decision-maker, fund circular economy projects not token clean-ups.

If you are a policy influencer, push for formal recognition of waste workers and strict enforcement of existing rules.

If you are a student, researcher, or activist, document what works and amplify it.

A zero-waste India is not a dream. It is a decision.

The cities have shown the path. The rest of the country now has to walk it.

Be part of the transition.

Start with your home, your ward, your organisation.

The future of waste in India is not waiting; it is being built.

Authored by- Sneha Reji