India’s Organic Policy Landscape: A Review

Over the past two decades, India has positioned itself as one of the largest organic producers in the world. According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, the country had over 4.43 million hectares under organic certification by 2023, yet this constitutes only about 2% of India’s net sown area.

The journey began with the National Programme for Organic Production (NPOP) in 2000, which laid out certification standards and export regulations. This policy framework was primarily designed to tap into lucrative European and American organic markets rather than to create a robust domestic organic ecosystem.

However, a significant policy shift came with the launch of Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) in 2015 under the National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture. This scheme marked an acknowledgment of organic farming not merely as an export-oriented sector but as a tool for soil health restoration, climate resilience, and farmer income diversification. Under PKVY, clusters of 50 acres each are supported for organic transition, providing farmers with training, certification subsidies, and marketing support.

Yet, implementation challenges remain. A NITI Aayog discussion paper pointed out that despite policy intent, fragmented certification processes, weak domestic market linkages, and limited awareness restrict India’s potential to replicate success stories like Sikkim, which became India’s first fully organic state in 2016. Sikkim’s transition demonstrates that consistent political will, holistic extension services, and assured procurement are indispensable to drive organic adoption.

Globally, India is often compared to Bhutan, which has committed to becoming a 100% organic nation. Bhutan’s policy design treats organic not as an alternative but as the mainstream, integrating it into national food security strategies. India’s policies, however, remain scattered between export promotion under APEDA and domestic promotion under PKVY, often creating overlaps and inefficiencies. As Earth5R’s research on sustainable urban-rural linkages points out, unless organic policy is treated as an integrated public health, environment, and livelihood strategy, isolated schemes will have limited impact.

Overall, while India’s organic policy landscape has evolved considerably, there is a need for a more unified, outcome-oriented framework that treats organic farming as essential for national nutrition security and environmental restoration, rather than a premium niche. Only then can India accelerate its journey from policy to plate.

Linking Agriculture with Public Health Outcomes

In recent years, the conversation around organic farming has shifted from being solely an environmental or lifestyle choice to a public health imperative. Multiple studies have underlined how conventional farming’s high pesticide residues correlate with rising non-communicable diseases. For instance, a Lancet Planetary Health study (2019) found that dietary risks, including exposure to pesticide residues, contribute significantly to the burden of disease in India.

Organic farming offers an opportunity to integrate agriculture with public health outcomes in a tangible way. According to the Indian Council of Medical Research, organic produce tends to have lower heavy metal contamination and reduced nitrate levels, which can otherwise be carcinogenic. In Sikkim, after its full organic transition, local health officials reported improved gut health indicators in communities consuming locally grown organic food, although systematic longitudinal studies remain limited.

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) also launched the “Jaivik Bharat” initiative to enhance consumer trust in organic products, marking an institutional recognition of organic’s health benefits. Moreover, Earth5R projects in Mumbai’s urban slums have shown that introducing small quantities of organic vegetables in midday meals for children improved haemoglobin levels over a six-month pilot, underscoring the potential of organic integration in public nutrition schemes.

Globally, countries like Denmark have implemented organic policies explicitly to reduce public health burdens. Their “Organic Action Plan 2020” aimed to double organic farmland while linking it with health-focused public procurement, a model India could adapt to local contexts. If agriculture is to be treated as a provider of not just food but health, organic must become an integral part of nutrition security strategies, ensuring a healthier future generation.

Procurement by Government for MDMs, Hostels, Anganwadis

One of the most effective ways to mainstream organic is through government procurement for public feeding programmes such as Mid-Day Meals (MDMs), hostels, and anganwadis. The Mid-Day Meal Scheme alone serves over 120 million children daily, representing a massive opportunity to create demand for local organic produce while enhancing nutrition quality.

States like Kerala have piloted organic procurement in select districts. Under its Organic Farming Policy, the state facilitated direct procurement from certified farmer groups for school feeding programmes, reducing chemical intake among children while providing farmers with assured markets. Similarly, in Madhya Pradesh, certain tribal hostels have integrated organic millets into their menus through partnerships with local Self-Help Groups and Farmer Producer Organisations.

However, challenges persist. A Centre for Policy Research report highlighted that procurement guidelines under MDM are often rigid, with cost ceilings making organic purchases difficult. Additionally, lack of local certification infrastructure delays procurement processes. To overcome these hurdles, Earth5R’s Sustainable School Meals project in Mumbai designed a community certification approach where urban farmer groups underwent participatory guarantee systems, enabling affordable organic supply to anganwadis without compromising traceability standards.

Globally, Brazil’s Zero Hunger Programme mandates that at least 30% of food procured for school meals is sourced from smallholder organic or agroecological farmers. This model has not only improved nutrition but revitalised local economies and reduced rural poverty. If adapted effectively, such policies could transform India’s public food systems into engines of health and environmental sustainability.

By integrating organic procurement into MDMs, hostels, and anganwadis, India can create a steady domestic market for organic produce, improve child health outcomes, and support small farmers transitioning to organic, moving closer to its vision of food as both nourishment and medicine.

Incentives for Farmers and Buyers

Incentives play a pivotal role in accelerating the shift towards organic farming. For farmers, transitioning to organic often comes with short-term yield uncertainties, labour intensiveness, and market risks. The Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) provides limited per-acre subsidies, but these cover only basic inputs like bio-fertilisers and training. A FAO report suggests that countries with robust organic transitions provide financial incentives for up to five years to cushion farmers during the conversion period.

Sikkim’s successful organic transition was partly due to strong government incentives, including free organic input distribution, assured market linkages, and capacity building programmes. Farmers were assured that despite possible initial yield reductions, long-term soil health improvement and premium market pricing would offset risks. However, such comprehensive incentive models remain rare across India.

On the buyer side, incentives remain minimal. Organic products continue to command a price premium of 20-40% over conventional produce in most urban Indian markets, restricting demand to higher-income groups. Countries like Austria and Denmark have implemented VAT exemptions on organic products to reduce retail prices, making them accessible to middle and lower-income consumers. In India, NITI Aayog’s organic policy review suggested GST waivers on organic inputs and products to enhance market competitiveness.

Additionally, Earth5R’s Urban Organic Markets project in Mumbai experimented with digital coupons for low-income households, redeemable against organic vegetables purchased from local community farmers, effectively incentivising healthier consumption while boosting farmer incomes. Such dual incentive models for both producers and consumers are crucial to break the perception of organic as a luxury and embed it into mainstream food systems.

Better Subsidy Models and Transition Support

Subsidies for organic farming in India have historically been input-focused rather than outcome-oriented. Under PKVY, farmers receive about ₹20,000 per hectare spread over three years, but as multiple evaluations show, this amount barely covers costs for bio-inputs, composting, and certification. In contrast, the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy provides area-based subsidies and compensatory payments for yield losses during the conversion period, recognising that ecosystem services offered by organic farms benefit entire communities.

States like Andhra Pradesh are experimenting with alternative models under the Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) approach, where subsidies are redirected towards training and farmer-to-farmer mentorship rather than input provision. According to a World Resources Institute study, ZBNF farmers have reported improved net incomes due to reduced chemical input costs and better soil moisture retention, indicating that subsidy design focusing on knowledge systems may be more effective than cash transfers alone.

However, transition support must go beyond subsidies. Farmers require handholding through certification processes, market linkage facilitation, and risk mitigation tools such as organic-specific crop insurance. For instance, in Maharashtra’s Nasik district, Earth5R worked with local Farmer Producer Organisations to design community-led Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) that reduced certification costs by 70%, while ensuring product credibility for urban buyers.

Globally, South Korea’s Organic Farming Promotion Act offers a model worth emulating. It combines transition subsidies with direct marketing support, research funding, and consumer awareness campaigns under a single policy umbrella, creating an ecosystem conducive for organic growth. In India, integrating such holistic transition support into existing agricultural schemes could accelerate adoption, ensuring that farmers do not face the burden of sustainability alone.

This infographic highlights the EU Organic Action Plan 2021-2027, showcasing targeted policies to boost organic production and consumption across Europe. It demonstrates how structured government actions can transform food systems and accelerate the organic movement from policy to plate.

Local Organic Mandis: Scaling Market Access

While India’s organic production potential is immense, market access remains one of its weakest links. Most farmers selling organic produce struggle to find assured local buyers, forcing them to either sell at conventional prices or bear high logistics costs to distant urban markets. The concept of local organic mandis offers a promising solution by bridging producers and consumers within the same geography.

States like Madhya Pradesh pioneered “Jaivik Setu”, a digital and physical organic market platform connecting organic farmers directly with urban consumers and institutional buyers. This model not only ensured fair prices for farmers but also enhanced consumer trust by providing traceability data on products sold. In Tamil Nadu, the Organic Farmers Market initiative in Chennai established weekly markets run entirely by organic farmer cooperatives, cutting out middlemen and building loyal consumer bases.

However, scaling local mandis requires infrastructure investments in cold chains, transport, and dedicated organic retail spaces within existing Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs). A Centre for Science and Environment report noted that without such dedicated spaces, organic produce often gets mixed with conventional produce, defeating certification integrity and consumer confidence.

Earth5R’s Urban Organic Markets project in Mumbai experimented with hyperlocal mandis set up in housing societies and office complexes, directly connecting small peri-urban farmers to consumers on weekends. These markets not only boosted farmer incomes by 25-40% but also created interactive platforms for consumers to understand cultivation practices, fostering trust and repeat purchases (Earth5R Urban Organic Markets).

Globally, Japan’s Teikei movement – farmer-consumer co-operatives where members commit to buying directly from farmers for a season – shows how local market structures rooted in trust can sustain organic economies without heavy government subsidies. India could adapt such models to strengthen its own local organic mandis, ensuring organic remains affordable and farmers remain profitable.

Public Awareness Campaigns That Have Worked

Changing consumer behaviour is critical to mainstreaming organic products. In India, awareness about organic’s benefits remains confined to urban elites, often driven by social media influencers or niche organic brands. However, public policy-driven awareness campaigns have shown potential to shift perceptions at scale.

One notable example is Sikkim’s statewide organic campaign prior to its full transition in 2016. The government ran multi-platform campaigns involving radio jingles, school workshops, street theatre, and organic fairs to familiarise citizens with the concept of organic, its environmental benefits, and its impact on health. This consistent narrative building created a sense of pride among citizens, branding Sikkim as an “organic state” rather than merely a policy intervention.

Another impactful initiative is FSSAI’s “Jaivik Bharat” logo campaign, which standardised organic labelling and ran educational outreach in metro cities to build consumer trust in certified products. According to FSSAI reports, this led to a 15% increase in organic sales in Delhi-NCR within a year of launch, indicating that standardisation combined with mass outreach can unlock latent demand.

Earth5R’s “Citizen Driven Organic” campaign in Mumbai also demonstrated the power of hyperlocal awareness. Through community workshops, rooftop farm demonstrations, and partnerships with Resident Welfare Associations, Earth5R educated over 10,000 urban residents on the health and environmental impacts of organic choices. As a result, multiple housing societies committed to weekly organic vegetable subscriptions directly from peri-urban farmers, sustaining farmer incomes while reducing carbon footprints from long-distance supply chains.

Globally, Denmark’s “Økologisk” (Organic) label campaign is credited with building one of the highest organic consumption rates in the world, where over 12% of total food sales are organic (Organic Denmark). Their model shows that when awareness campaigns are embedded into national food policies and supported by market access initiatives, organic transitions become mainstream rather than marginal.

Training Government Extension Officers on Organic

For any agricultural transformation to succeed, last-mile knowledge dissemination is critical. In India, government agricultural extension officers (AEOs) have traditionally focused on Green Revolution technologies—chemical fertilisers, hybrid seeds, and pesticide use. However, with organic farming gaining policy traction, it becomes imperative to retrain and reorient these officers to guide farmers effectively during organic transitions.

A FAO assessment on organic extension services found that lack of technical knowledge among frontline staff is one of the greatest bottlenecks in organic adoption. In India, only a few states like Sikkim and Kerala have mandated organic-specific training modules for their extension officers. Sikkim’s success story was underpinned by its strategy of training over 700 extension officers in organic practices before rolling out the policy statewide, ensuring farmers received scientifically grounded, locally adapted advice.

However, in most Indian states, AEOs still receive minimal training on organic standards, certification protocols, or biological pest management. This knowledge gap often results in misinformation, farmer resistance, or ineffective implementation.

Recognising this, Earth5R’s Urban Farming and Sustainable Agriculture training modules include extension officer workshops, equipping them with hands-on skills in composting, integrated pest management, and certification processes. Officers trained under this initiative in Mumbai and Nashik reported improved confidence in guiding peri-urban organic farmers.

Internationally, Thailand’s Department of Agriculture launched an Organic Agriculture Training Centre for Extension Workers, resulting in a 20% rise in national organic acreage within five years due to improved farmer support. India can emulate such initiatives by integrating organic agriculture into the National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management (MANAGE) curricula, creating a new generation of organic-savvy extension officers who act as catalysts rather than barriers to change.

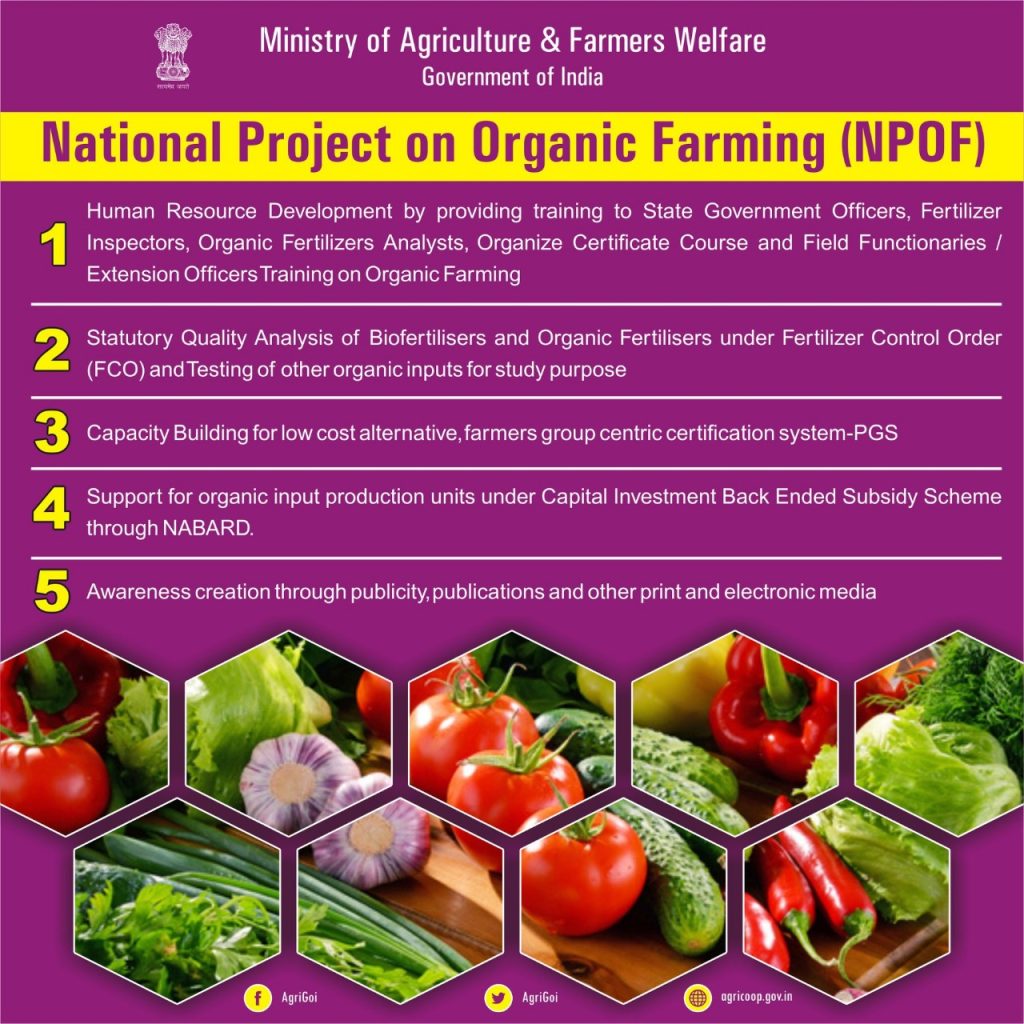

This infographic highlights the National Project on Organic Farming (NPOF), showcasing how India’s government builds capacity, ensures quality, and funds organic initiatives. It reflects the policy backbone essential to accelerate the organic movement from farm to consumer plate.

Building District-Level Organic Clusters

Scaling organic farming in India requires moving beyond scattered individual farms to district-level organic clusters that can harness economies of scale, streamline certification, and create robust market linkages. The Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) already promotes cluster-based organic farming, but its current implementation is often limited to small, fragmented groups with insufficient infrastructure support.

Sikkim’s organic transition offers a powerful example of cluster-based planning. By declaring the entire state organic, it effectively created a mega cluster with unified extension services, input supply chains, and marketing strategies. Inspired by this, Madhya Pradesh has identified 20 organic clusters for targeted development, focusing on tribal regions where traditional low-input farming systems make organic conversion more feasible.

Earth5R’s Blue Cities Organic Initiative integrates cluster development with urban market demand, creating city-linked organic clusters where peri-urban farmers are organised into cooperative networks that supply directly to urban consumers. This model not only strengthens farmer incomes but also reduces carbon footprints by shortening supply chains.

Globally, the European Union’s Organic Action Plan 2020-2024 prioritises regional organic clusters with shared processing units, storage facilities, and marketing cooperatives, ensuring that small organic farmers remain competitive in globalised food markets (EU Organic Action Plan). India can adapt such models by identifying district-level organic corridors linked to public procurement and retail supply chains, creating a critical mass of organic production and consumption.

Building district-level clusters thus transforms organic from a niche practice to an integrated agricultural development strategy, enabling economies of scale, infrastructural viability, and policy focus to accelerate the organic movement across India.

What Next: A Five-Year Action Plan

As India stands at the crossroads of nutrition security, environmental restoration, and farmer income enhancement, organic agriculture offers an integrated pathway forward. However, without a clear, time-bound action plan, organic will remain an isolated experiment rather than a mainstream agricultural revolution. Here is a research-driven five-year roadmap to accelerate the organic movement from policy to plate.

First, the government must integrate organic farming goals into national nutrition and health policies, moving beyond treating it solely as an agricultural practice. The NITI Aayog’s organic policy discussion paper recommends making organic procurement mandatory for a percentage of Mid-Day Meals, anganwadi supplies, and public hospitals, thereby guaranteeing demand while improving public health outcomes.

Second, investments in training extension officers and farmers must be scaled up rapidly. Drawing from Thailand’s organic extension training model, India could establish regional organic training centres under MANAGE to build technical capacity across states. Without robust knowledge dissemination, policy incentives risk underutilisation.

Third, financial incentives must become outcome-based rather than input-based. Instead of small input subsidies, India can adopt the European Union model of area-based payments and ecosystem service rewards, compensating farmers for yield risks and recognising the public environmental benefits their organic farms generate.

Fourth, India should prioritise district-level organic clusters integrated with urban market demand. Earth5R’s Blue Cities model has shown that linking city consumption with peri-urban organic production creates viable economic ecosystems (Earth5R Blue Cities Model). Scaling such models nationally will require investment in certification, storage, and transport infrastructure tailored for organic value chains.

Finally, consumer awareness campaigns must go beyond urban elites. Drawing lessons from Denmark’s Økologisk campaign, India can build a national organic brand identity that combines health, sustainability, and farmer welfare, making organic aspirational yet accessible. The FSSAI’s Jaivik Bharat initiative is a start, but deeper integration into mainstream advertising and digital platforms is essential (Jaivik Bharat FSSAI).

In essence, India’s five-year organic action plan must treat organic farming not as an isolated policy domain but as an intersection of public health, environment, agriculture, and livelihoods. As Earth5R’s research continually highlights, only when organic becomes a collective mission—supported by farmers, consumers, policymakers, and civil society—can India move swiftly from policy documents to everyday plates, ensuring health for people and planet alike.

From Vision to Reality: Mainstreaming Organic for India’s Future

India’s organic movement stands at a critical juncture. While policies like PKVY and Jaivik Bharat have laid the foundation, scaling organic farming into a mainstream solution for health, environment, and livelihoods requires unified action, strong market linkages, robust training systems, and public awareness. By adopting a holistic, integrated approach that links farmers to public health, markets to nutrition, and policy implementation, India can transform organic from a niche aspiration into a national reality, ensuring food that heals people and restores the planet.

FAQs on From Policy to Plate: How Governments Can Accelerate the Organic Movement

What is India’s current policy framework for organic farming?

India’s organic policy framework includes the National Programme for Organic Production (NPOP) for certification and exports, and the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) for domestic organic promotion through cluster-based farming.

How much area in India is under organic farming?

As of 2023, India has over 4.43 million hectares under organic certification, which is around 2% of the country’s net sown area.

Why is organic farming linked to public health?

Organic farming reduces exposure to harmful pesticides and heavy metals, lowering risks of cancer, hormonal disruptions, and other health issues associated with chemical-intensive agriculture.

How can government procurement accelerate organic adoption?

By procuring organic produce for Mid-Day Meals, anganwadis, and hostels, the government can ensure stable demand for farmers while improving nutritional outcomes for vulnerable populations.

Which Indian state is fully organic?

Sikkim became India’s first fully organic state in 2016, transitioning all its farmland to chemical-free cultivation.

What are the challenges in current organic subsidy models?

Current subsidies are input-based and insufficient to cover transition costs or yield risks, limiting farmers’ incentive to shift from conventional to organic farming.

How do local organic mandis help farmers?

Local organic mandis connect farmers directly with consumers, reducing transport costs, ensuring fair prices, and building consumer trust through transparent sourcing.

What role do extension officers play in promoting organic farming?

Extension officers provide technical training, certification guidance, and problem-solving support to farmers; without their expertise in organic practices, adoption rates remain low.

Which countries are models for organic policy success?

Denmark, Bhutan, and Austria are notable for integrating organic into national health, environment, and food security strategies, achieving high organic consumption and production rates.

How can consumer incentives make organic more affordable?

Measures like VAT or GST exemptions, digital coupon schemes, and public procurement can reduce organic retail prices, making it accessible beyond elite urban consumers.

What is the impact of Earth5R’s organic initiatives?

Earth5R’s projects, such as the Urban Organic Markets and Blue Cities model, have increased farmer incomes by up to 40% and improved urban access to fresh organic produce.

How does organic farming contribute to environmental sustainability?

Organic farming improves soil health, biodiversity, and water retention while reducing chemical runoff and greenhouse gas emissions, making it climate-smart agriculture.

What are district-level organic clusters?

These are geographical areas where organic farming is promoted collectively with shared certification, storage, and marketing infrastructure to ensure economies of scale.

What is the Jaivik Bharat initiative?

Jaivik Bharat is an FSSAI initiative to standardise organic certification logos and build consumer trust in organic products through awareness campaigns and labelling.

Why is training extension officers in organic farming important?

Without specialised training, extension officers cannot effectively guide farmers on organic practices, certification, or market linkages, limiting the impact of policy schemes.

How does organic farming affect farmer incomes?

While transition periods may see yield dips, long-term organic farming can increase net incomes by reducing input costs and tapping premium markets, especially with proper market access.

What lessons can India learn from Bhutan’s organic journey?

Bhutan treats organic as a national food security strategy rather than a niche market, ensuring policy coherence, farmer support, and public awareness for nationwide adoption.

How can public awareness campaigns boost organic consumption?

Campaigns that educate citizens on health and environmental benefits build demand, as seen in Sikkim, Denmark, and Earth5R’s community outreach models.

What is the Teikei model in Japan?

Teikei is a farmer-consumer cooperative system where consumers commit to buying directly from farmers each season, ensuring stable markets and fostering trust.

What is the way forward for India’s organic movement?

India needs a five-year action plan integrating public health, market incentives, extension training, and consumer awareness to mainstream organic farming from policy to everyday plates.

Take Action: Be Part of India’s Organic Revolution

The journey from policy to plate requires collective effort. As a consumer, choose organic to support farmer livelihoods and protect your health. If you’re a policymaker or professional, advocate for integrated organic policies that prioritise public health, environment, and farmer welfare. Together, we can transform organic from a luxury to a mainstream movement that nourishes people and restores our planet.

-Authored by Pragna Chakraborty