The Global ESG Tide: Navigating a New Era of Corporate Transparency

A seismic shift is underway in the world of global finance and corporate governance. Fuelled by an investor-led demand for accountability, assets under management with a focus on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria are projected to skyrocket, potentially reaching $33.9 trillion by 2026, according to a PwC report. This monumental flow of capital is transforming how businesses operate and report on their performance.

What was once the domain of voluntary Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), often viewed as a peripheral public relations activity, has now evolved into a critical, board-level imperative. Think of it this way, if CSR was like a company’s occasional charitable donation, ESG reporting is its comprehensive annual health check-up, scrutinizing its very DNA, from its carbon footprint to its supply chain ethics and the diversity of its leadership.

This evolution, however, is not uniform. The global stage is a complex mosaic of developing regulations. This article delves into the dynamic and often divergent paths being forged by three economic powerhouses: the European Union (EU), the United States (US), and India. Each region is crafting its own narrative, responding to unique market pressures and political realities.

From the EU’s ambitious, rule-setting directives to the US’s market-driven, politically contested approach, and India’s strategic leap towards a comprehensive framework, a fascinating story is unfolding. While a global trend towards more stringent and standardized ESG reporting is clear, the pace, scope, and philosophical underpinnings of these changes vary significantly, creating a complex and dynamic environment for multinational corporations.

We will explore the EU’s role as the global benchmark setter, unpack the regulatory tug-of-war within the US, and examine India’s rapid transition from a compliance-focused model to one that champions sustainability. By analyzing these distinct journeys, we gain a clearer picture of the future of corporate accountability in an increasingly interconnected world.

Brussels Sets the Gold Standard: How the EU’s ESG Rules Are Reshaping Global Business

In the global push for corporate accountability, the European Union has firmly positioned itself not as a follower, but as the chief architect of the future. Driven by its ambitious European Green Deal, a commitment to make the continent climate-neutral by 2050, Brussels is deploying a comprehensive suite of regulations designed to embed sustainability into the very fabric of corporate finance and strategy.

This regulatory revolution is spearheaded by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), a game-changing piece of legislation that dramatically upgrades its predecessor, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). The NFRD was a good first step, but research revealed its limitations, namely inconsistent data and a narrow scope that allowed too many companies to avoid disclosure.

The CSRD addresses these shortcomings with force. Firstly, it massively expands the net, increasing the number of companies required to report from around 11,700 to nearly 50,000. This includes all large EU companies and even non-EU companies with substantial operations within the bloc, a move with significant global repercussions.

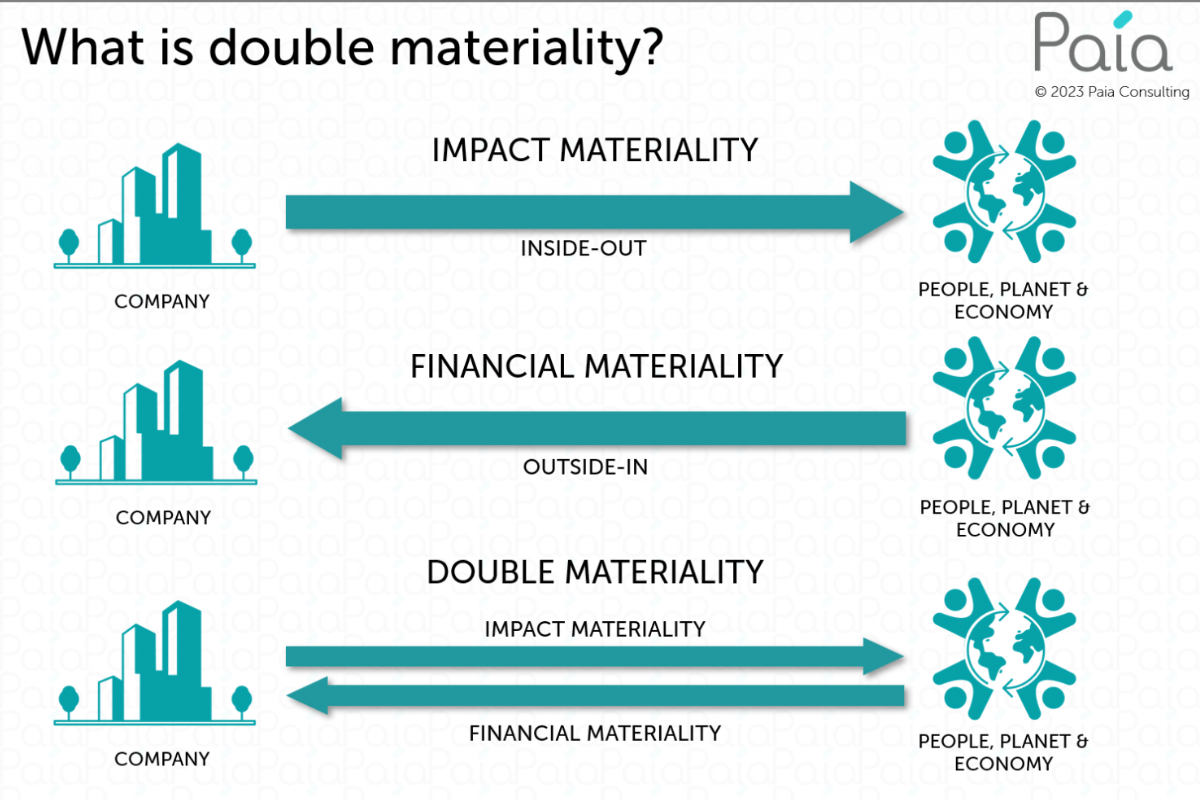

At the heart of the CSRD is the groundbreaking concept of double materiality. This is a profound departure from traditional reporting, which typically only considers how sustainability issues might affect a company’s financial health. The EU’s approach demands a two-way view, almost like a corporate conscience check.

Imagine a large automaker. Under a single materiality lens, it would report on how climate risks like flooding might disrupt its factories and impact profits. This is the “outside-in” perspective. Double materiality, however, forces the company to also report on its own impact on the world, such as the CO2 emissions from the cars it sells and the environmental footprint of its manufacturing. This is the “inside-out” view.

By mandating that companies report on both how the world affects their balance sheet and how their balance sheet affects the world, the EU is fundamentally redefining what constitutes material business information. This holistic perspective ensures that a company’s true societal and environmental costs are brought into the light.

To prevent this from becoming a vague, box-ticking exercise, the CSRD is underpinned by a detailed set of rules known as the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). Developed by the advisory group EFRAG, these standards act as a meticulous instruction manual, specifying exactly what information companies must disclose across a wide range of environmental, social, and governance topics, ensuring the data is comparable and decision-useful for investors.

Further reinforcing this structure is the EU Taxonomy Regulation, a scientific classification system that provides a clear definition of what can be considered an environmentally sustainable economic activity. It functions like a “green dictionary” for business, aiming to channel investment toward activities that genuinely contribute to the EU’s climate goals. Under the CSRD, companies must disclose the proportion of their activities that align with this taxonomy, creating a clear metric of their green transition.

Finally, to build trust and combat the pervasive threat of “greenwashing,” the CSRD introduces a mandate for third-party assurance. For the first time, the sustainability information companies publish will need to be independently audited, much like their financial statements. This verification step is critical for lending credibility to ESG reports.

The EU’s regulatory package doesn’t stop at reporting. The proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) pushes companies from disclosure to direct action. It requires them to actively identify, prevent, and mitigate adverse human rights and environmental impacts throughout their global value chains. This holds companies accountable not just for their own actions, but also for those of their suppliers, a necessary step confirmed by extensive research from bodies like the International Labour Organization on labour conditions in global supply chains.

Through this interconnected web of ambitious regulations, the EU is not just changing the rules for its own member states; it is creating a powerful ripple effect, setting a de facto global standard that multinational corporations everywhere must now strive to meet.

Wall Street’s ESG Tug-of-War: The US Forges a Contentious Path on Disclosure

While Europe has laid down a clear regulatory highway for ESG reporting, the United States presents a far more complex picture, one defined by market-driven momentum clashing with deep political divisions. For years, the American approach was a voluntary patchwork, allowing companies to choose from an alphabet soup of reporting frameworks like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the industry-specific SASB Standards.

This landscape began to fundamentally change with the intervention of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). After a period of intense debate and revision, the SEC finalized its landmark climate-related disclosure rule, marking the federal government’s most significant step toward mandating climate transparency. The rule requires public companies to report on their climate-related risks and their strategies for managing them.

A central element of the final rule is the disclosure of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. While the requirements for direct (Scope 1) and energy-related (Scope 2) emissions are now a compliance reality for large companies, the more complex value-chain (Scope 3) emissions reporting remains a key point of contention, with the SEC having adopted a phased-in approach with safe harbor provisions to ease the burden.

Crucially, the entire SEC framework is anchored by the long-standing legal concept of financial materiality. This principle acts as the North Star for all disclosures. The guiding question for American companies is not “What is our impact on the planet?” but rather, “Is this climate information something a reasonable investor would consider important when making a decision to buy or sell our stock?”

This focus creates a clear philosophical divide with the EU’s “double materiality” standard. To use an analogy, the US rule asks a coastal property firm to report on the financial risk of rising sea levels to its assets. The EU rule would ask the same question, but also require the firm to report on the environmental impact of its construction on the local coastal ecosystem.

The journey of the SEC’s rule has been anything but smooth. Since its proposal, it has been embroiled in fierce political and legal battles. The “anti-ESG” movement has gained traction in several states, arguing that the SEC is overstepping its congressional mandate by venturing into environmental policy. This has resulted in a flurry of lawsuits, creating a cloud of uncertainty and complicating corporate compliance efforts.

Yet, even with the regulatory tug-of-war in Washington, the most powerful force shaping ESG disclosure in the US remains the market itself. Institutional investors and asset managers, who collectively manage trillions of dollars, have been unequivocal in their demand for better data. Major firms like BlackRock and State Street continue to emphasize that understanding climate risk is integral to fulfilling their fiduciary duty to clients.

This investor pressure is powerfully expressed through shareholder activism. Year after year, corporate proxy ballots are filled with resolutions demanding greater transparency on everything from climate lobbying to workforce diversity, proving that regardless of the final regulatory outcome, companies face direct accountability pressure from their owners.

In the absence of a comprehensive federal standard that rivals the EU’s, individual states have begun to step into the void. California has emerged as a clear leader, passing its own aggressive climate disclosure laws, SB 253 and SB 261. As of late 2025, large public and private companies doing business in the state are actively preparing for these new, stringent reporting requirements, which in some ways go beyond the SEC’s rule.

This state-level action is creating a complex compliance patchwork. For national and multinational corporations, navigating these differing state and federal rules is becoming a significant challenge, a situation that may ultimately increase pressure for a more unified national approach to avoid death by a thousand regulatory cuts.

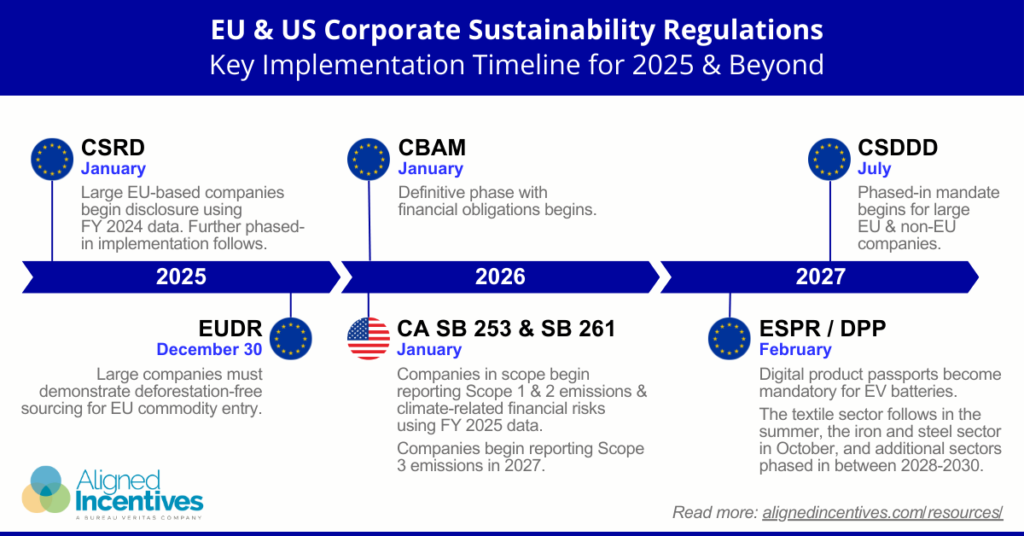

This timeline illustrates the rapid acceleration of corporate sustainability regulations, highlighting the critical deadlines companies face in the EU and US for mandatory climate, supply chain, and due diligence reporting starting in 2025.

From Mandated Charity to Market Mantra: India’s Rapid ESG Evolution

India’s journey into the world of sustainability reporting follows a unique and accelerated trajectory, one that is deeply rooted in its socio-economic context. The nation’s formal tryst with corporate responsibility began not with environmental concerns, but with a social focus through the landmark Companies Act of 2013. This law mandated that companies of a certain size spend 2% of their profits on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), effectively institutionalizing corporate philanthropy.

While this created a culture of social spending, the approach was often disconnected from core business strategy. The real strategic shift came with the introduction of a new framework by the country’s market regulator, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). This new mandate moved the conversation decisively from CSR to the more holistic and globally recognized ESG paradigm.

At the center of this transformation is the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR). Phased in for India’s top listed companies, the BRSR represents a quantum leap in disclosure expectations. It is built upon the nine principles of the government’s National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct (NGRBC), which cover a wide spectrum of issues from environmental stewardship to ethical conduct and consumer welfare.

A key feature of the BRSR is its tiered structure, which distinguishes between “Core” and “Leadership” indicators. The BRSR Core requires disclosure on a set of essential and quantifiable metrics, ensuring a baseline of comparable data across industries. The “Leadership” indicators are voluntary, encouraging more progressive companies to report on advanced sustainability practices, creating a clear path for continuous improvement.

Importantly, the BRSR is not simply a copy of Western frameworks. It is tailored to India’s realities as a developing nation. The framework places significant emphasis on social indicators that are critical to the country’s growth, such as job creation in smaller towns, community development projects, and assessments of social impact, making it uniquely relevant to the Indian context.

The drive for this change is threefold. Firstly, there is a strong regulatory push from SEBI, which has been proactive in aligning Indian markets with global best practices. Secondly, investor demand is surging. Foreign institutional investors are increasingly applying global ESG screening criteria to their Indian portfolios, while domestic ESG-focused mutual funds have seen a marked rise in popularity.

Finally, for India’s globally ambitious companies, robust ESG reporting has become a license to operate internationally. Accessing global capital markets and integrating into sophisticated supply chains now requires a level of transparency that goes far beyond traditional financial statements.

The link between on-the-ground action and high-level reporting is where the true impact lies. Consider the work of organizations like Earth5R, whose projects in waste management and sustainable livelihoods for local communities provide a perfect illustration of the BRSR in action. Their initiatives, such as training women in Mumbai to upcycle plastic waste into new products, directly address key reporting principles.

A corporate partner supporting such a program could translate this impact into clear metrics for their BRSR filing. The environmental benefits align with Principle 2 (providing goods and services sustainably) by promoting a circular economy. The social impact, through creating employment and empowering women, directly corresponds to Principle 8 (promoting inclusive growth and equitable development).

This demonstrates how sustainability reporting in India is evolving from a mere compliance document into a genuine reflection of a company’s engagement with society. The BRSR framework is effectively creating a data-driven bridge between corporate activity and the nation’s broader sustainable development goals, pushing Indian businesses to prove that their growth is not just profitable, but also responsible and inclusive.

A Tale of Three Frameworks: Charting the Path to a Global ESG Language

As we have seen, the European Union, United States, and India are each navigating the ESG landscape with distinct philosophies. The EU is writing a detailed, prescriptive rulebook for the world, the US is crafting a legal framework focused squarely on investor risk, and India is authoring a national charter that balances global ambition with local social priorities.

These diverging paths have created a complex environment for multinational corporations, forcing them to become multilingual in the language of sustainability reporting. The core differences and emerging similarities in these regional approaches can be clearly seen when compared side-by-side:

| Feature | European Union (CSRD) | United States (SEC Rule) | India (BRSR) |

| Materiality | Double Materiality | Financial Materiality | Financial & Social Impact |

| Scope | ~50,000 EU & non-EU firms | US-listed public companies | Top 1,000 listed firms (phased) |

| Assurance | Mandatory (Limited, then Reasonable) | Required for GHG emissions | Voluntary (BRSR Core assured) |

| Primary Driver | Top-down Regulation | Investor Pressure & Litigation Risk | Regulator-led (SEBI) |

The most significant divergence remains the fundamental debate over materiality. The EU’s expansive “double materiality” lens captures a company’s full societal and environmental footprint, while the US SEC rule remains strictly anchored to what an investor needs to know to assess financial risk. India charts a middle path, prioritizing financial data while embedding key social impact metrics relevant to its national context.

Despite these differences, a powerful trend toward convergence is undeniable. All three jurisdictions are moving away from voluntary reporting towards mandatory disclosure frameworks. Each has placed a heavy emphasis on climate-related risks, and all are beginning to demand greater transparency in complex global supply chains.

Into this complex arena has stepped a potential great harmonizer: the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). Formed to meet intense market demand for a common reporting language, the ISSB has issued a set of standards, including IFRS S1 and S2, designed to serve as a global baseline.

The ISSB standards act as a potential bridge, creating a foundation of investor-focused information that other jurisdictions can build upon. While not replacing regional rules like the CSRD or BRSR, they offer a common denominator that can streamline reporting for companies and provide comparable data for investors, pushing the world one step closer to a truly global ESG language.

This visual breaks down the key ESG concept of double materiality, which requires companies to report on the two-way relationship between their operations and society.

From Messy Data to Meaningful Metrics: Tech to the ESG Rescue

The global push for robust ESG reporting faces a formidable hurdle, the challenge of data. For many companies, gathering accurate, reliable, and auditable information, especially from deep within complex supply chains, is like trying to assemble a puzzle with pieces scattered across the globe. This data dilemma creates a significant risk of unintentional errors and intentional “greenwashing,” which can erode investor trust.

Fortunately, a new wave of technology is emerging as a powerful ally in this fight for transparency. Digital innovation is transforming ESG from a manual data-wrangling exercise into a strategic, data-driven discipline. Companies are now deploying sophisticated tools to bring clarity to the chaos.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Big Data platforms can sift through enormous, unstructured datasets to identify ESG risks and opportunities, from analyzing satellite imagery for deforestation to gauging employee sentiment online. The Internet of Things (IoT) provides a direct line to the source, with smart sensors on factory floors giving real-time, verifiable data on everything from water usage to energy consumption.

Furthermore, technologies like blockchain are offering the promise of radical transparency in supply chains. By creating an immutable digital ledger, companies can trace raw materials from source to final product, providing unprecedented assurance about ethical sourcing and combating human rights abuses. These tools are becoming essential for turning raw data into the credible insights that regulators and investors now demand.

The Age of Accountability: ESG’s Permanent Place in the Boardroom

The journey of ESG reporting in the European Union, the United States, and India reveals a clear, overarching narrative. Though the regulatory language and cultural priorities differ, the destination is the same, a new era of corporate accountability where a company’s value is measured by more than just its financial bottom line.

The future of corporate disclosure lies in the concept of Integrated Reporting, where the increasingly artificial wall between financial and sustainability reports dissolves completely. This reflects the market’s mature understanding that a company’s environmental stewardship and social license are inextricably linked to its long-term financial health.

Leading corporations are already proving this thesis. They are moving beyond a compliance-based approach to see ESG as a strategic tool for value creation, using its principles to drive innovation, mitigate deep-seated risks, and attract a new generation of talent and capital.

Ultimately, the transparency demanded by this global movement is about more than just data points on a page. It is the foundational element for rebuilding trust between business and society, and it is the essential compass that will guide capital towards building a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable global economy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is ESG reporting?

ESG reporting is the process through which a company discloses data and information related to its performance on environmental, social, and governance issues. It goes beyond traditional financial reporting to provide investors and other stakeholders with a holistic view of the company’s long-term sustainability and ethical impact.

Why has ESG reporting become so important recently?

The importance of ESG reporting has surged due to a massive increase in demand from investors who now recognize that ESG factors, like climate risk or supply chain ethics, can have a material impact on a company’s financial performance. This shift is turning ESG from a niche interest into a mainstream financial consideration.

What is the main difference between CSR and ESG?

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is often focused on philanthropy and community outreach, which can be separate from the core business. ESG, on the other hand, is about deeply integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into the company’s core business strategy and measuring its performance on these metrics.

What is the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)?

The CSRD is a landmark EU law that requires nearly 50,000 companies, including many non-EU firms with significant operations in Europe, to conduct detailed reporting on a wide range of sustainability issues. It mandates the use of specific standards and requires the information to be independently audited.

What does “double materiality” mean in the European context?

Double materiality is a core principle of the EU’s CSRD. It requires a company to report on two perspectives: first, how sustainability issues affect its own financial performance (the “outside-in” view), and second, how the company’s own operations impact society and the environment (the “inside-out” view).

What is the EU Taxonomy?

The EU Taxonomy is a scientific classification system, or a “green dictionary,” that defines which economic activities can be considered environmentally sustainable. Companies subject to the CSRD must report on how their business activities align with this taxonomy, helping to direct investment toward greener projects.

How does the EU’s approach affect non-EU companies?

The CSRD has a significant global reach. Non-EU companies that have a substantial business presence in the European Union, such as having a certain turnover or a subsidiary there, will also be required to comply with its detailed reporting rules, effectively exporting the EU’s standards globally.

What is the main focus of the SEC’s climate rule in the US?

The main focus of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) climate rule is on financial materiality. It requires US-listed companies to disclose information about climate-related risks that a “reasonable investor” would consider important for making investment decisions, including data on greenhouse gas emissions.

Why is ESG reporting so politically contested in the United States?

ESG reporting is politically contested in the US due to a debate over whether it constitutes financial regulation, which is within the SEC’s mandate, or environmental policy, which some argue is not. This has led to legal challenges and an “anti-ESG” movement, creating uncertainty for businesses.

What is driving ESG reporting in the US besides federal regulation?

The primary drivers in the US are powerful market forces. Large institutional investors and asset managers are demanding better ESG data to assess long-term risk. Additionally, shareholder activism and new, aggressive disclosure laws passed at the state level, particularly in California, are pushing companies toward greater transparency.

What is the BRSR framework in India?

The Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR) is the mandatory reporting framework introduced by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). It requires India’s top listed companies to report on their performance across nine core principles of responsible business conduct.

How did India’s reporting evolve from its mandatory CSR law?

India’s journey began with the Companies Act of 2013, which mandated a 2% profit spend on CSR. The BRSR represents a major evolution from this compliance-driven approach to a more strategic and holistic ESG disclosure framework that is integrated with a company’s core business operations and performance.

What makes India’s BRSR framework unique?

The BRSR is tailored to India’s context as a developing economy. Alongside global ESG metrics, it includes specific indicators that focus on social impact, such as job creation in smaller towns and engagement with marginalized communities, reflecting the country’s national development priorities.

What is “greenwashing” and how do new regulations address it?

Greenwashing is the act of making false or misleading claims about the positive environmental impact of a company’s products or operations. New regulations, especially the EU’s CSRD, address this by mandating third-party assurance, which requires that a company’s sustainability data be independently audited and verified, similar to financial data.

What is the role of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB)?

The ISSB was established to create a global baseline for sustainability reporting that is focused on enterprise value. Its standards, IFRS S1 and S2, are designed to be a common language that can be used by companies and investors worldwide, helping to harmonize the different regional approaches.

How is technology helping with ESG reporting challenges?

Technology is crucial for overcoming data challenges. Artificial intelligence (AI) helps analyze vast datasets, the Internet of Things (IoT) provides real-time, accurate metrics from operations, and blockchain offers a transparent and traceable way to verify claims about complex supply chains.

What is the difference between financial materiality and double materiality?

Financial materiality, the focus in the US, considers only how sustainability issues impact a company’s financial condition. Double materiality, the standard in the EU, includes this but also requires the company to report on its own impact on the environment and society.

Are private companies also affected by these new ESG rules?

Yes, increasingly so. While many regulations target publicly listed companies, the EU’s CSRD also applies to large private companies. Furthermore, smaller private companies are indirectly affected as they are part of the value chains of larger companies that are now required to report on their supply chain’s ESG performance.

What are “Scope 3” emissions?

Scope 3 emissions are all the indirect emissions that occur in a company’s value chain. This includes emissions from the products it buys from suppliers and from the use of its products by customers. They are often the largest source of a company’s carbon footprint and the most difficult to measure.

What is the future of corporate reporting?

The future points towards “Integrated Reporting,” where the distinction between a company’s annual financial report and its sustainability report disappears. The two will merge into a single, cohesive document that communicates how a company creates value over the long term through all forms of capital, including financial, human, and natural.

The Road Ahead: From Insight to Impact

The global shift towards mandatory and transparent ESG reporting is more than a regulatory trend; it is a fundamental redefinition of corporate success. The information and frameworks discussed are not just for compliance officers and asset managers, but are tools available to everyone who believes in a more sustainable and equitable future.

Whether you are a business leader, an investor, an employee, or a consumer in India and across the world, your actions matter.

- For business leaders, the time is now to move beyond a compliance mindset. Use these frameworks not as a checklist, but as a strategic lens to uncover risks, drive innovation, and build a more resilient and trusted enterprise for the decades to come.

- For investors, use your capital as your voice. Demand clearer, more comprehensive data from the companies you invest in and support funds that practice active stewardship to drive positive change.

- For all of us, stay informed and engaged. Ask questions about the sustainability practices of the companies you work for and buy from. Championing transparency is a collective responsibility, and by doing so, we can all contribute to building an economy that values both profit and principle.

~ Authored by Abhijeet Priyadarshi