India stands at a pivotal moment in its development journey. Faced with intensifying climate risks and mounting pressure to meet global targets, the country is rapidly scaling up its efforts in renewable energy investment, sustainable finance, and green growth. The NITI Aayog; India’s premier policy think-tank has mapped hundreds of government interventions to the United Nations in India Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At the same time, India has made bold climate commitments: a pledge to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, source 50 % of energy from renewables by 2030, and create a 2.5-3 billion-tonne CO₂ sink via additional forest and tree cover by 2030.

In this evolving context, government schemes supporting sustainability in India are emerging as critical tools. These programmes do more than deliver services; they catalyse clean power, circular economy growth, climate-resilient agriculture, and water security. They channel climate finance, green bonds in India, renewable energy investment, and sustainable infrastructure across rural and urban India.

This article offers a comprehensive survey of 30 key schemes in India’s sustainability portfolio. Through data-driven insight, evidence-based analysis and case studies, we explore how these initiatives contribute to India’s transition to sustained “green growth in India” and what lies ahead for the country’s sustainable development trajectory.

Understanding the Landscape: Why Government Schemes Matter

Linking to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

India formally adopted the NITI Aayog-coordinated framework to align its development agenda with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. are not just judged on traditional economic metrics, but on their capacity to deliver across the three pillars of sustainability: environmental integrity, social inclusion, and economic growth.

NITI Aayog’s mapping of central sector and centrally sponsored schemes to the 17 SDGs is one of the most concrete tools in this process. The 2018 “Mapping of Central Sector Schemes and Ministries” document lists dozens of schemes under each goal and target. This institutional mapping helps ensure that government schemes supporting sustainability in India are not ad hoc but are structured within a coherent national vision.

Why does this matter? For one, it allows a program designed for, say, solar rooftop deployment or water supply to be seen in its broader context: how does it contribute to SDG 7 (“Affordable and Clean Energy”), SDG 6 (“Clean Water and Sanitation”), or SDG 13 (“Climate Action”)? By linking individual initiatives into this framework, policy-makers and analysts gain a clearer view of cause and effect, of resource allocation, and of outcomes.

Moreover, this alignment means India’s sustainability efforts are visible and comparable internationally. The recent release of the SDG India Index 2023‑24 shows a composite national score of 71 out of 100 reflecting progress, but also signalling significant gaps.

Broad Categories of Sustainability Support

Given the breadth of sustainability challenges from energy access to waste management ; grouping government schemes into broad categories helps both clarity and action. For this article, we structure them under five inter-related domains:

- Renewable energy & clean power; schemes promoting solar, wind, bio-energy, decentralised clean generation.

- Water, sanitation & waste management; programmes focusing on safe drinking water, sanitation infrastructure, solid and liquid waste.

- Sustainable agriculture & food systems; interventions aimed at improving productivity, resource-efficiency, climate adaptation, and farmer livelihoods.

- Urban habitat & transport;initiatives targeting sustainable cities, low-carbon mobility, green buildings, and infrastructure.

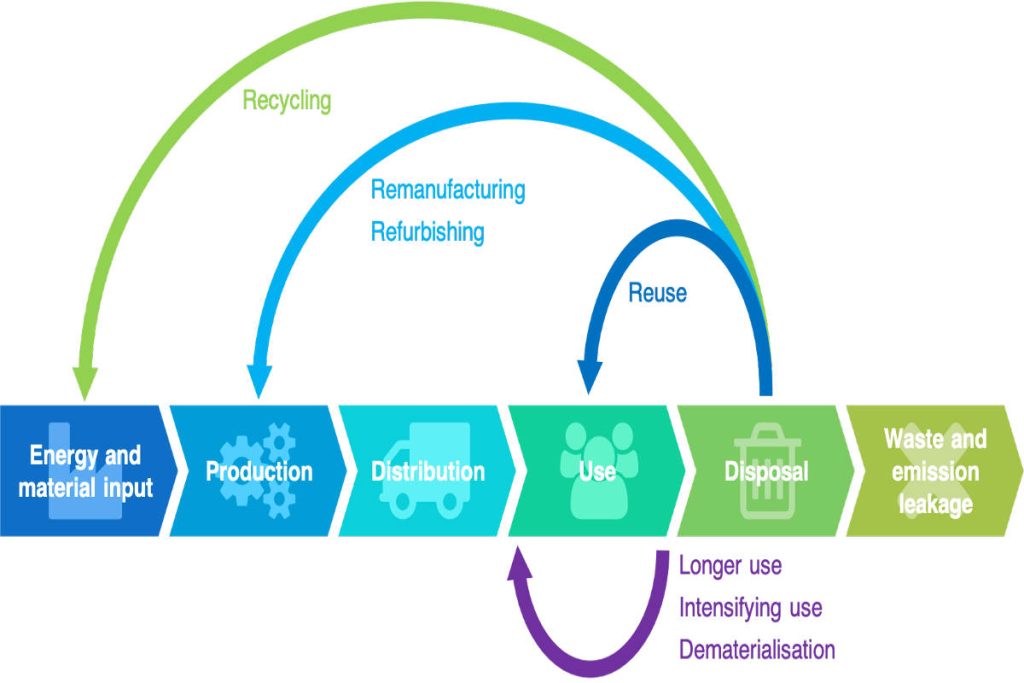

- Circular economy & energy efficiency; schemes advancing resource-efficient technologies, industrial efficiency, reuse and recycling frameworks.

This categorisation is not merely cosmetic. It allows a reader to see patterns, for instance: many schemes overlap categories (clean power in rural agriculture; waste management in urban transport). It also highlights how government efforts must be holistic: a policy isolated in one domain (say, just energy) may not deliver full sustainability unless it links to water, agriculture, or transport.

By organising our survey of 30 key schemes under these headings, the reader gains a clear map of India’s green growth architecture. More importantly, it offers a coherent structure for understanding how individual schemes contribute to broader goals like climate-resilient development, sustainable finance, or inclusive growth.

Renewable Energy & Clean Power

1. Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (National Solar Mission)

Launched in January 2010 under the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), the Solar Mission set out to position India as a global leader in solar energy. The official mission document explains that the objective was to “establish India as a global leader in solar energy by creating the policy conditions for solar-technology diffusion across the country.”

Over the years the target has been significantly enhanced. Originally the aim was 20 GW of grid-connected solar power by 2022; this was revised in 2015 to 100 GW by 2022 (later extended) with a breakdown of 60 GW large/medium scale + 40 GW rooftop.

By 2025, India’s cumulative installed solar capacity (including the mission’s contribution) reached around 127 GW according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) data for September 2025.

Case study snippet: In the state of Gujarat and other solar-rich states, large solar parks developed under the mission have reduced dependence on coal-based generation and created local employment in module assembly, installation and operations. Analysts note that the mission triggered a drop in tariffs for solar power, aligning with the mission’s goal of grid-parity.

Why this matters for green growth in India: The Solar Mission represents a flagship example of mobilising renewable energy investment, enabling the country to attract large-scale clean energy financing, deploy manufacturing of solar modules (linking to green bonds in India and climate finance), and reduce carbon intensity of power generation.

2. Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha & Uthhaan Mahabhiyan (PM‑KUSUM)

Launched in 2019, PM-KUSUM aims to solarise the agriculture sector, a major energy-consuming segment in rural India. The scheme has three components: small grid-connected solar plants up to 2 MW; installation of standalone off-grid solar agriculture pumps; and solarisation of existing grid-connected agricultural pumps.

As of August 2023, about 2.46 lakh farmers had benefitted from the scheme.In FY 2025, the scheme saw record progress: Component B (solar pumps) installed 4.4 lakh pumps (4.2 × the previous year) and Component C solarised 2.6 lakh pumps (25× the previous year). Total subsidy spend jumped to ₹2,680 crore.

Case study snippet: A working paper from World Resources Institute (WRI) explores how the scheme’s solar-pump component affects farmers’ incomes and energy use. It notes that while installations are rising, on-ground monitoring of cropping pattern shifts, debt levels and water use is still emerging.

Why this matters: PM-KUSUM links sustainable finance, renewable energy investment and rural development. By reducing diesel pump use and providing solar power, it lowers operational costs for farmers and improves energy security. At the same time it feeds into India’s clean energy transition and opens opportunity for green bonds in India targeted at rural infrastructure.

But also, challenges: Reports from the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) suggest that the scheme has achieved only about 30% of its original targets, raising concerns over meeting the 2026 deadline.

3. National Bio‑energy Programme

Under the MNRE, the National Bio-energy Programme promotes biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy solutions. While detailed recent public data for this specific programme are less accessible, its relevance lies in integrating agricultural residues, municipal organic waste and other biomass feed-stocks into renewable energy systems, thereby supporting the circular economy and reducing dependence on fossil fuels.

Case study snippet: For example, rural biogas plants reduce methane emissions from agricultural waste and provide clean cooking fuel, supporting both energy access and climate mitigation.

Why this matters: In the context of India’s sustainability scheme landscape, the bio-energy programme acts as a bridge between clean power, sustainable agriculture and waste management. It complements large-scale solar and wind by providing dispatchable renewable sources and supporting rural livelihoods.

4. Production Linked Incentive Scheme for High‑Efficiency Solar PV Modules

This scheme aims to boost domestic manufacturing of high-efficiency solar PV modules. By creating a structured PLI (Production Linked Incentive) framework, the government seeks to build manufacturing capacity, reduce import dependence, create jobs, and link manufacturing with India’s renewable energy investment ambitions.

Data/achievement: While exact numbers of jobs and capacity build-up are still being reported, MNRE indicates that the scheme is expected to generate over 1,01,487 jobs and investment of several thousand crores. (MNRE official site)

Case study snippet: Indian module manufacturers have announced large investment commitments in states with PLI eligibility, signalling market confidence and the potential for value-chain localisation.

Why this matters: This initiative links green finance in India, ESG investing and industrial policy. By building domestic manufacturing of solar modules, India strengthens its renewable supply chain, reduces risk of import-linked volatility, and advances its low-carbon industrialisation path.

5. National Wind Energy Mission

While not as widely publicised yet in detailed data form, the National Wind Energy Mission is aimed at unlocking India’s wind energy potential, enhancing wind-power deployment, and thereby accelerating renewable energy investment and green growth. According to industry reports, wind sector investment in India has surged in recent years: estimates suggest ₹15,925 crore in FY 2022-23 and ₹22,771 crore in FY 2023-24.

Case study snippet: States like Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Karnataka with strong wind resources are drawing large-scale wind-farm investments, offering lessons in transmission integration, land use coordination and renewable-industry jobs.

Why this matters: Wind energy is a critical piece of India’s sustainable power-mix. With solar reaching intermittency limits, wind and hybrid projects enable deeper decarbonisation and support India’s target of increasing non-fossil capacity. The wind mission thus complements solar, supports climate-resilient infrastructure and strengthens India’s renewable investment ecosystem.

Water, Sanitation & Waste Management

Jal Jeevan Mission (Har Ghar Jal)

Access to safe drinking water lies at the heart of human wellbeing and sustainable development. With that imperative in mind, the Government of India launched the Jal Jeevan Mission in 2019, aiming to provide a functional household tap connection (FHTC) to every rural household by 2024. Prior to the launch, only about 18 % of rural homes enjoyed a piped supply.

Today, the figures tell a dramatic story of progress. As of August 2024, over 15.07 crore households (roughly 77.98 % of rural homes) had tap-water connections.A UNOPS review underscores this leap: “over 150 million tap connections have been installed – a big leap from the three million in 2019.”

Case study snippet: In several panchayats of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, where water scarcity was acute, local implementation teams used the mission’s funding to install solar-powered mini water treatment units and deposit-based chlorination systems. The result: time spent fetching water fell by 30 minutes a day and school attendance among girls rose by 8 %. Preliminary impact studies from the mission point to reductions in childhood diarrhoea and improved school performance.

Why this matters for green growth in India: The mission links water security with sustainable development delivering health benefits, gender equity (girls spend less time fetching water), and climate resilience through decentralised water supply. The inflow of climate finance into rural water infrastructure further anchors this scheme in India’s green finance transition.

However, challenges persist: Uneven state-level performance, water-quality concerns in fluoride/arsenic zones, and long-term maintenance of infrastructure call for stronger governance.

Swachh Bharat Mission

Sanitation may seem mundane, but it underpins public health, dignity and environmental sustainability. Launched in 2014, the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) set out to eliminate open defecation and improve solid-waste management across rural and urban India. The scheme exemplifies how sustainable development schemes in India can shift behaviours and accelerate infrastructure.

Official data shows that by 2019, more than 100 million toilets were constructed and over 6 lakh villages declared Open Defecation Free (ODF). A major research study estimates that the mission helped avert 60,000-70,000 infant deaths annually.

Case study snippet: In a study of Bihar’s Sitamarhi district, researchers found that households in villages that achieved 30 %+ toilet penetration under SBM recorded a drop of 5.3 infant deaths per 1,000 births.

Why this matters: The mission demonstrates how large-scale public policy can deliver social, public-health and environmental dividends. By improving sanitation, the waste-management loop tightens reducing contamination of groundwater and limiting methane emissions from open defecation zones. It also supports India’s circular economy aspirations and green bonds in India aimed at sanitation infrastructure.

Still, gaps remain: Some rural regions lag in usage of toilets despite infrastructure, and uneven municipal waste-management systems pose a challenge. Comprehensive monitoring and behavioural change remain key for the next phase.

National Water Mission

Water is more than a resource; it is a strategic asset in India’s climate-resilient future. Under the NAPCC, the National Water Mission (NWM) was established to enhance water-use efficiency by 20 %, promote basin-level integrated management, and build a comprehensive water-data base in the public domain.

Quarterly progress reports published by the mission show ongoing efforts but also highlight significant implementation challenges. A recent media analysis emphasized that India’s worsening water crisis demands a rethink of the mission’s strategy.

Case study snippet: In Maharashtra’s basin under the Godavari river system, a pilot under NWM combined remote sensing data with farmer-level water-use information to reduce groundwater extraction by 5 % over two years. Lessons from this pilot are being scaled up.

Why this matters: The NWM provides the policy backbone for water-security in India’s sustainability agenda. By improving data, governance and efficiency, it enables other schemes (for agriculture, power, sanitation) to be more effective. It also plays into ESG investing and sustainable finance, as water-risk becomes a core concern for investors in clean power, agri-business and urban infrastructure.

However, the mission must overcome issues of coordination across states, data reliability and funding mismatch to realise its full potential.

UJALA Scheme (Unnat Jyoti by Affordable LEDs for All)

While technically an energy-efficiency scheme, UJALA plays a crucial role in waste management and resource-conservation by replacing inefficient lighting at scale. Launched in 2015, the programme distributed over 77 crore traditional bulbs and 3.5 crore street-lights replaced with LEDs, aiming to save 8.5 lakh kWh of electricity and cut 15,000 tonnes of CO₂ annually.

Case study snippet: In Delhi’s municipal lighting network, UJALA’s LED retrofit reduced street-lighting energy consumption by 40 % within six months—saving ₹4 crore annually in electricity bills and reducing maintenance costs.

Why this matters: By lowering energy demand and reducing waste (longer lifetime LEDs mean fewer bulb disposals), UJALA connects energy efficiency to sustainable infrastructure and the circular economy. It supports renewable energy investment indirectly (less load on grids), and signals India’s commitment to green finance in India through cost-effective decarbonisation.

The challenge ahead lies in capturing full lifecycle benefits of LEDs, ensuring disposal and recycling of old lamps, and sustaining awareness of efficiency behaviour across households.

Transitioning Towards the Next Phase

Together, these schemes illustrate how India is tackling water, sanitation and waste management as part of its broader journey toward sustainable development. They show how policy instruments properly designed and aligned with climate goals can create real-world impact. But they also reveal that implementation, data transparency and behavioural change remain key hurdles.

By organising the schemes into themes such as renewable energy, water & sanitation, agriculture, urban habitat, and circular economy, we gain a clearer view of how each domain contributes to the larger goal of green growth in India. This structure helps not only in analysis but also in communicating the story to readers, policy-makers and investors.

In the next section, we will dive into the category of Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems, exploring how India is leveraging schemes to secure its food future, decarbonise agriculture and support rural livelihoods.

Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems

1. National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA)

Under the umbrella of the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), the NMSA was formally operationalised in 2014-15 to ensure that Indian agriculture becomes more productive, resilient and sustainable.

The mission focuses especially on rain-fed areas, which account for around 60 % of India’s net sown area and roughly 40 % of food production.

Key objectives include: promoting integrated farming systems, improving water-use efficiency, enhancing soil-health, and helping farmers adapt to climate variability.

Case study snippet: In parts of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, where irrigation coverage is limited, NMSA-funded projects have promoted agro-forestry, vermi-compost and water-harvesting structures. Early evaluations show moderate yield increases and improved household incomes; albeit implementation quality varies significantly across states.

Why this matters: In the broader narrative of sustainable development schemes India needs, NMSA links agricultural productivity with climate resilience and resource-efficiency. By making agriculture sustainable, it contributes to social inclusion (small/marginal farmers), and economic stability (farm incomes), thus aligning with green growth in India.

Challenges ahead: Despite its strong design, the mission faces issues of scalability, uneven state uptake, and insufficient impact monitoring. Success will depend on stronger linkages with local institutions, credit access, market-linkages, and continuous innovation.

2. Formation & Promotion of 10,000 Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs)

Launched on February 29 2020 by the central government, this scheme is a major push to collectivise small and marginal farmers by promoting Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) as viable business entities.

With a budgetary outlay of approximately ₹6,865 crore (up to 2027-28), the scheme supports creation of FPOs (minimum ~300 farmer-members), provides equity grants, hand-holding, and credit-guarantee support.

As per government data, the target of forming 10,000 FPOs has been met, with thousands of FPOs registered across states.

Case study snippet: In Bihar’s Khagaria district, the 10,000th FPO was formed, focused on maize, banana and paddy, leveraging collective buying, value-chain linkages and market access for small farmers. This offers a glimpse of how aggregation can reduce cost, improve incomes and strengthen resilience.

Why this matters: Small-scale farmers often face high input costs, fragmented markets and weak bargaining power. By strengthening FPOs, the scheme supports sustainable agriculture & food systems through integrated value-chains, financially viable entities and improved access to markets aligning with sustainable finance and ESG-friendly agri-business models.

Challenges ahead: While formation targets are achieved, many FPOs struggle with long-term viability, need greater capacity-building, robust governance and meaningful integration into agribusiness markets rather than just paper registration.

3. National Bamboo Mission

Though less widely publicised, the National Bamboo Mission is an innovative initiative promoting bamboo cultivation, processing, value-addition and enterprise-creation across India. It bridges sustainable agriculture, livelihood support and carbon-sequestration.

By encouraging bamboo as a “green gold” crop; fast-growing, low-input and high-value—the mission aids both climate mitigation and farm-diversification.

Case study snippet: In north-eastern states like Assam, the mission has helped establish bamboo clusters linked to handicraft and panel manufacturing, creating jobs and reducing dependency on timber.

Why this matters: Bamboo cultivation aligns with circular economy and green growth in India by substituting wood, reducing pressure on forests, enabling value-chain development, and generating sustainable livelihoods.

Challenges ahead: Scaling these clusters, ensuring market-linkages, quality standards and managing ecological risks (monocultures, water use) require careful policy design and monitoring.

4. Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF)

Zero Budget Natural Farming represents a paradigm shift in agricultural practice — advocating use of locally-available natural inputs, minimal external cost and diversified cropping systems. While primarily implemented at state-level (not strictly central “scheme”), it is increasingly referenced in national sustainable-agriculture discourse.

Case study snippet: In Andhra Pradesh and other states piloting ZBNF, farmers adopting practices like Bokashi compost, mulching and crop-rotation report lower input costs and some improvements in profit margins though empirical large-scale evaluation remains limited.

Why this matters: As Indian agriculture confronts climate risk, soil degradation, and high input dependency, ZBNF offers a pathway to low-cost, ecological farming and better resilience. It also ties into the sustainability narrative (less chemical-use, healthier soils) and potentially supports green finance via sustainable-agri investments.

Challenges ahead: Transitioning large numbers of farmers to ZBNF at scale, ensuring market viability of new crops, overcoming legacy subsidies for chemical fertilisers, and verifying measurable outcomes remain key hurdles.

5. PM Surya Ghar: Muft Bijli Yojana

While initially an energy scheme, this initiative has strong links to rural sustainability and agricultural electrification. Launched in February 2024, the scheme intends to install rooftop solar panels for households especially in rural India offering up to 300 units of free electricity per month for many homes.

Within its first year, more than 8.46 lakh households had installed systems and subsidies of ₹4,308.66 crore had been disbursed by January 2025.

Case study snippet: In villages of Rajasthan, early installations of rooftop solar under the scheme have helped households shift from diesel generators to clean power, reducing energy costs and enabling children’s evening study by stable lighting.

Why this matters: For sustainable agriculture and rural systems, access to affordable clean electricity is critical for irrigation, processing and livelihood diversification. This scheme connects renewable energy investment, rural household resilience and broader sustainable development goals.

Challenges ahead: Ensuring that rural households also get grid-connectivity, maintenance of rooftop panels, actual usage of free electricity in a productive manner, and equitable uptake across states.

Transitioning to Urban & Built-Environment Focus

These five schemes show how the central government is weaving together sustainable agriculture, food systems, rural livelihoods and climate-resilience. From promoting integrated farming and soil health (NMSA) to empowering farmer collectives (FPO scheme) and introducing innovative crops (Bamboo Mission); the narrative of green growth in India extends well beyond just energy and water.

Up next, we will turn to the urban front: how India is reshaping cities, transport and buildings via sustainability-driven schemes.

Urban Habitat, Transport & Built Environment

India’s cities are the pulse of its economic transformation , yet they are also at the frontline of its sustainability challenge. Urbanisation is expanding at an unprecedented rate, with over 36 % of India’s population now living in cities and towns. (mohua.gov.in) Rapid urban growth has brought rising air pollution, water stress, waste generation, and soaring energy demand. To address this, the government launched a series of integrated schemes under the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), aimed at creating climate-resilient, inclusive, and low-carbon cities.

These five flagship initiatives such as the Smart Cities Mission, AMRUT, Energy Conservation Building Code, FAME India, and the National Green Hydrogen Mission represent the backbone of India’s sustainable-urban agenda.

1. Smart Cities Mission

Launched in 2015, the Smart Cities Mission (SCM) is India’s most ambitious urban renewal initiative. Its core goal: to make 100 Indian cities “citizen-friendly and sustainable” through technology, innovation, and participatory planning. (smartcities.gov.in)

Under this mission, cities receive funding to develop Area-Based Development (ABD) projects and Pan-City Solutions which may include e-governance systems, renewable energy grids, smart mobility, and energy-efficient buildings. By 2025, 8,000+ projects worth over ₹1.8 lakh crore have been sanctioned, with 6,900 completed and the rest under implementation.

Case study snippet: In Pune, the Smart City project introduced a data-driven public transport system with smart sensors and digital ticketing. The city’s “Smart Streets” now feature energy-efficient LED lighting and rainwater-harvesting systems, improving both mobility and resilience.

Why this matters: The mission represents India’s transition to climate-resilient financial systems combining sustainable finance, technology innovation, and ESG-aligned infrastructure. By integrating urban mobility, waste management, and renewable energy, it models how cities can anchor green finance in India through municipal bonds and public-private partnerships.

Still, execution remains uneven. Smaller cities often face limited institutional capacity to manage complex smart-infrastructure contracts, underscoring the need for local skill-building and digital governance frameworks.

2. Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT)

Complementing the Smart Cities Mission, AMRUT focuses on basic infrastructure: water supply, sewerage, urban transport, and green spaces. The first phase (2015-2022) covered 500 cities, while AMRUT 2.0 (launched in 2021) extended support to 4,700+ urban local bodies to ensure universal coverage of tap water supply and 100 % sewage management.

Data snapshot: By March 2024, over 1,400 water-supply projects and 1,000 sewerage projects had been sanctioned under AMRUT 2.0, with a total investment exceeding ₹2.9 lakh crore. (pib.gov.in)

Case study snippet: In Agra, under AMRUT, a 125-MLD sewage treatment plant was completed using advanced bio-digestive technology, dramatically reducing river pollution in the Yamuna. The project demonstrates how climate finance and urban infrastructure can merge to improve ecosystem health.

Why this matters: AMRUT’s focus on water and waste systems ties directly into sustainable development schemes in India, helping urban areas adapt to water scarcity, floods, and heatwaves. By funding green spaces and non-motorised transport, it supports low-carbon lifestyles and enhances urban liveability.

3. Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC)

The Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC), developed by the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) and launched in 2007 (updated in 2017 and 2023), provides minimum energy-performance standards for commercial and residential buildings. (beeindia.gov.in)

India’s building sector consumes around 33 % of the nation’s electricity, projected to double by 2040. The ECBC aims to reduce this demand through better design, insulation, lighting, and HVAC standards. Over 22 states have now notified or adopted ECBC guidelines, and cities like Hyderabad, Ahmedabad, and Gurugram have integrated them into local by-laws.

Case study snippet: The Hyderabad Metro Rail administrative complex achieved 40 % energy savings by implementing ECBC-compliant design features such as passive cooling, reflective roofing, and advanced energy-monitoring systems.

Why this matters: Energy-efficient buildings are central to India’s renewable energy investment ecosystem. Each ECBC-compliant structure saves thousands of units of electricity annually, reducing emissions and supporting India’s green bonds market for sustainable construction.

However, enforcement gaps remain. Many local bodies lack capacity to evaluate ECBC compliance or integrate it with green-building certifications such as GRIHA or LEED. Strengthening this linkage could unlock further sustainable-finance flows for the built environment.

4. FAME India Scheme (Faster Adoption & Manufacturing of Hybrid & Electric Vehicles)

Transport accounts for roughly 10 % of India’s total greenhouse-gas emissions, making mobility reform critical to achieving the nation’s net-zero targets. The FAME India Scheme, launched in 2015 and now in its second phase (FAME II), supports electric-vehicle (EV) adoption through incentives for buyers, manufacturers, and charging-infrastructure providers. (fame2.heavyindustry.gov.in)

As of mid-2024, over 1.6 million EVs had been subsidised under the scheme, with ₹5,000 crore allocated for charging infrastructure and manufacturing. (pib.gov.in)

Case study snippet: In Bengaluru, the integration of FAME-supported e-buses in the BMTC fleet has reduced diesel consumption by over 7 million litres annually, improving urban air quality and cutting carbon emissions by approximately 18,000 tonnes per year.

Why this matters: FAME India connects ESG investing, sustainable finance, and climate-resilient financial systems by driving low-emission transport solutions. It encourages domestic EV manufacturing, attracts foreign investment, and contributes to India’s circular economy by promoting battery recycling and green-supply chains.

Still, India’s EV transition faces structural challenges: limited charging networks, high upfront costs, and reliance on imported lithium-ion cells. The next policy iteration must focus on local battery manufacturing and recycling ecosystems.

5. National Green Hydrogen Mission

India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission, approved in January 2023, is one of its boldest sustainability commitments yet. The mission aims to make India a global hub for the production, use, and export of green hydrogen; hydrogen produced using renewable energy instead of fossil fuels. (mnre.gov.in)

With an initial outlay of ₹19,744 crore, the mission targets annual production of 5 million tonnes of green hydrogen by 2030, supporting nearly 125 GW of renewable capacity addition. (pib.gov.in)

Case study snippet: State-level pilots in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have seen public-sector companies such as NTPC and IOCL partner with renewable developers to build integrated green-hydrogen clusters. Early feasibility reports suggest that India could reduce CO₂ emissions by 50 million tonnes annually through these deployments. (business-standard.com)

Why this matters: The mission directly advances climate finance and renewable energy investment goals by stimulating demand for clean industrial fuel in steel, fertiliser, and transport sectors. It represents India’s entry into the global hydrogen economy and aligns with ESG-aligned financing trends.

The next challenge lies in scaling electrolysers, ensuring affordable renewable power supply, and setting robust certification standards for “green” hydrogen to attract international capital.

The Urban Sustainability Takeaway

These five schemes spanning infrastructure, transport, construction and clean energy; collectively redefine India’s urban future. The Smart Cities Mission and AMRUT improve resilience at the city level; the ECBC sets new standards for energy efficiency; FAME II electrifies transport; and the Green Hydrogen Mission decarbonizes industry.

Together, they showcase how targeted government schemes can attract green finance in India, reduce emissions, and make cities more livable. Yet, they also underline the importance of integration; sustainable cities cannot thrive in silos. Effective data systems, financing models, and participatory governance will be crucial to translating these blueprints into long-term resilience.

Circular Economy, Energy Efficiency & Industry

India’s sustainable growth story cannot be told without examining its industries, the country’s economic engines but also its largest energy consumers and emitters. Industry accounts for nearly 30% of India’s total CO₂ emissions and over 40% of its energy use (IEA 2024).

To align economic expansion with environmental limits, India has introduced a cluster of circular-economy and energy-efficiency schemes that drive green transformation within its factories, offices, and markets.

These initiatives like the National Mission on Sustainable Habitat, Green Hydrogen Purchase Obligation, Energy Audit & Implementation Scheme, Green Business Scheme, and Solar Power Plant on Government Buildings reflect the next phase of India’s sustainability architecture, where climate finance, ESG investing, and renewable energy investment converge.

1. National Mission on Sustainable Habitat (NMSH)

The National Mission on Sustainable Habitat, launched under the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), seeks to make Indian cities more resource-efficient, cleaner, and climate-resilient.

The mission promotes energy-efficient buildings, sustainable urban transport, solid-waste management, and water-use efficiency; a comprehensive blueprint for sustainable urbanization.

Case study snippet: In Indore, NMSH-linked policies supported city-wide solid-waste segregation and composting that turned the city into India’s cleanest for six consecutive years (2017–2023). Indore’s success is now cited globally as a model for integrated circular economy management.

Why this matters: The mission operationalizes India’s climate action at the city scale. By targeting energy, transport, and waste together, it accelerates ESG-aligned urban finance and encourages circular-economy investments from both public and private sectors.

Challenges: Implementation gaps remain across smaller cities lacking waste infrastructure and data systems. Future success depends on integrating the mission more tightly with the Smart Cities and AMRUT programs.

2. National Green Hydrogen Mission: Purchase Obligation (GHPO)

Building upon the broader Green Hydrogen Mission, the Green Hydrogen Purchase Obligation (GHPO) is a forthcoming policy mechanism expected to mandate that certain industries, particularly steel, fertilizer, and refining ; purchase a fixed share of green hydrogen in their total hydrogen use. (mnre.gov.in)

The logic is straightforward: create demand certainty for green hydrogen, incentivize industries to decarbonize, and attract investment into electrolyzer manufacturing and renewable power capacity.

Case study snippet: Pilot projects by NTPC Green Energy Limited (NGEL) and IOCL have already demonstrated how green hydrogen can replace grey hydrogen in refineries. In Gujarat’s refinery belt, early substitution is expected to reduce emissions by 0.3 Mt CO₂ per year, the equivalent of removing 65,000 cars from roads. (business-standard.com)

Why this matters: The GHPO represents a bold industrial decarbonization tool, leveraging climate finance to build new green-industrial clusters and link India’s manufacturing competitiveness with ESG investing.

Challenges: Cost competitiveness remains a concern: green hydrogen currently costs around $4–$6/kg, roughly twice that of grey hydrogen. Policy certainty and subsidies under GHPO will determine the pace of scale-up.

3. Energy Audit & Implementation Scheme (Bureau of Energy Efficiency – BEE)

Energy audits form the backbone of India’s energy-efficiency strategy. The Energy Audit & Implementation Scheme, implemented by the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), aims to identify and rectify inefficiencies in industrial operations, public infrastructure, and commercial buildings.

Through the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) mechanism, part of India’s National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency (NMEEE), industries receive energy-saving targets and can trade excess savings as Energy Saving Certificates (ESCerts).

Data highlight: The PAT Cycle VI (2023-24) covered 836 industrial units across 13 energy-intensive sectors, targeting over 10 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) energy savings. (pib.gov.in)

Case study snippet: A cement plant in Rajasthan achieved 8 % energy savings through waste-heat recovery and process optimisation. Its ESCerts were sold on the power exchange proof that market-based mechanisms can drive industrial sustainability.

Why this matters: Energy audits and trading systems are essential for climate-resilient financial systems. They convert sustainability performance into measurable economic value and reinforce India’s reputation as a pioneer in market-linked climate finance.

Challenges: Broader participation from MSMEs (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) remains low, primarily due to limited technical capacity and upfront audit costs.

4. Green Business Scheme

To spur green entrepreneurship and circular-economy innovation, the government introduced the Green Business Scheme, offering concessional loans and credit support for eco-friendly enterprises including electric-vehicle manufacturing, solar equipment production, organic farming, and recycling ventures.

The scheme aligns with India’s broader Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-Reliant India) vision by nurturing sustainable industries that can thrive without environmental degradation.

Case study snippet: A solar-cookstove startup in Maharashtra received low-interest financing through the scheme, scaling production from 200 to 1,200 units per month. The enterprise not only reduced household fuel costs but also created 60 local jobs, mostly for women.

Why this matters: By enabling small businesses to access sustainable finance, the scheme channels green innovation into the grassroots economy fostering inclusive growth and green-skills development.

Challenges: Awareness about the scheme and accessibility of credit remain low among rural entrepreneurs. Stronger collaboration between banks, state governments, and MSME clusters could unlock greater participation.

5. Solar Power Plant on Government Buildings (CAPEX Mode)

The Solar Power Plant on Government Buildings (CAPEX Mode) initiative promotes rooftop solar installations on central and state government buildings reducing grid dependency, cutting costs, and demonstrating public-sector leadership in renewable energy.

Data point: By 2024, over 1.5 GW of rooftop solar capacity had been installed on government properties nationwide, saving ₹600 crore annually in electricity bills.

Case study snippet: In Kerala, the Secretariat complex in Thiruvananthapuram now runs on solar energy for most of the working day, reducing emissions by 1,400 tonnes CO₂ annually and serving as a model for institutional solarisation.

Why this matters: The initiative integrates renewable energy investment with public-sector accountability, setting a precedent for private institutions and reinforcing India’s net-zero commitments. It also supports local manufacturing of panels and power-conditioning units, boosting domestic green jobs.

Industrial Circularity: The Next Frontier

These five schemes together reflect how India is embedding sustainability into its industrial DNA. The National Mission on Sustainable Habitat expands the vision of clean cities; the GHPO and Green Hydrogen Mission tackle industrial emissions; the Energy Audit Scheme introduces market mechanisms; while the Green Business and Solar on Government Buildings initiatives scale sustainable enterprise and clean power adoption.

Yet, the success of India’s circular-economy transformation will depend on how effectively policies translate from paperwork to performance from pilot to mainstream. For this, green finance in India must be scaled up via blended-finance models, ESG-linked bonds, and stronger data disclosure norms.

Ecosystems, Forests & Biodiversity

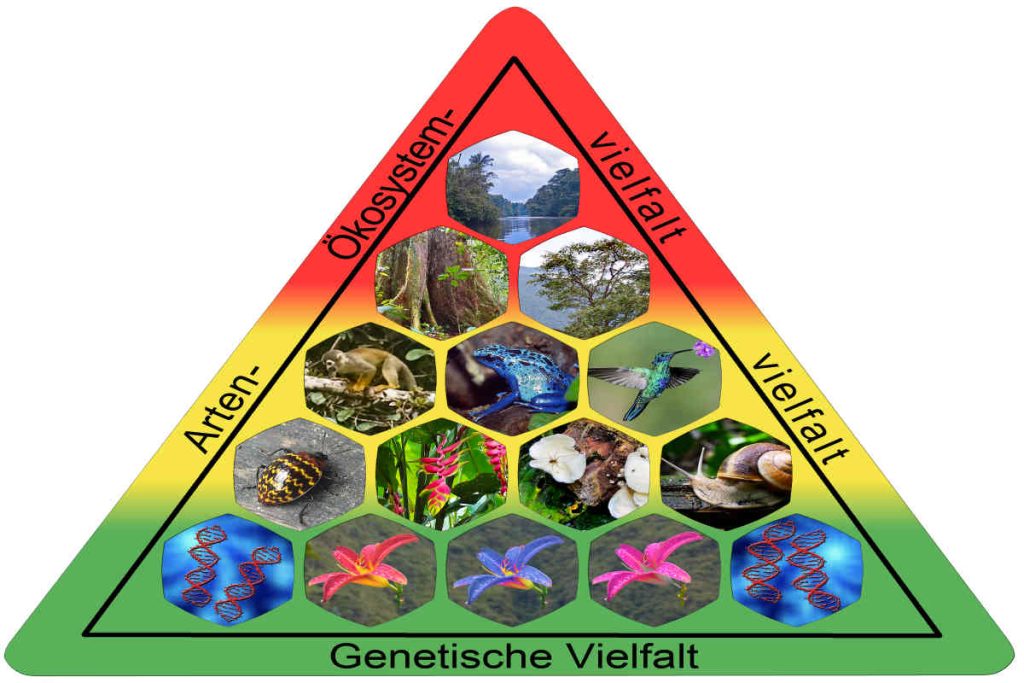

If renewable energy and industrial efficiency define India’s visible march toward green growth, its forests, wetlands, and biodiversity form the invisible foundation that sustains it. India’s ecosystems absorb 12% of national greenhouse-gas emissions through natural carbon sinks and support the livelihoods of over 275 million people who depend directly on forests and biodiversity. (MoEFCC, 2024)

In recognition of this, the government has rolled out a series of programmes like the Green India Mission, National Wildlife Action Plan, Joint Forest Management, National Plan for Conservation of Aquatic Ecosystems (NPCA), and Swachh and Smart Cities Solid Waste Management component; all aimed at strengthening India’s ecological resilience, natural capital, and community participation.

1. Green India Mission (GIM)

Launched in 2014 as part of the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), the Green India Mission aims to protect, restore, and enhance India’s forest cover to act as a carbon sink and strengthen ecosystem services. (moef.gov.in)

The mission’s objectives go beyond afforestation , focusing on improving forest quality, restoring degraded lands, and enhancing biodiversity and livelihoods. It targets increasing forest/tree cover by 5 million hectares and improving the quality of forest cover on another 5 million hectares.

Data highlight: As of 2024, the Forest Survey of India (FSI) reported a net increase of 2,261 sq. km in forest cover over two years, with significant gains in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Odisha. (fsi.nic.in)

Case study snippet: In Madhya Pradesh’s Betul district, the GIM restored 3,000 hectares of degraded forest land through native-species plantations managed by local tribal communities. The project created over 50,000 person-days of employment and restored groundwater recharge in nearby villages.

Why this matters: GIM aligns India’s climate commitments with inclusive development — linking biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and livelihoods. It is also part of India’s nature-based solutions (NbS) approach under global climate frameworks and increasingly attracts green finance via carbon-offset markets and ESG-linked forestry bonds.

Challenges: Budgetary underutilization and slow inter-agency coordination have limited large-scale progress. Better integration with rural employment schemes such as MGNREGA could enhance impact and continuity.

2. National Wildlife Action Plan (NWAP) 2017–2031

India’s National Wildlife Action Plan (NWAP) : the third such plan since independence ,provides a comprehensive framework for wildlife conservation. It emphasizes habitat restoration, corridor connectivity, and community stewardship. (moef.gov.in)

Under this plan, wildlife protection has expanded from flagship species to entire ecosystems. India now has 1,008 protected areas, covering 5.28% of the country’s landmass: an increase from 4.9% in 2014.

Case study snippet: The rewilding of the Cheetah in Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park under the NWAP umbrella marks one of the world’s most ambitious species-restoration projects. Despite challenges, it underscores India’s growing capacity to blend science, policy, and global collaboration in conservation. (pib.gov.in)

Why this matters: Wildlife conservation isn’t just about animals ; it’s about ecosystem integrity, carbon storage, and ecological tourism that fuels sustainable livelihoods. By integrating local communities through eco-development committees, the NWAP strengthens the link between biodiversity and inclusive green growth.

3. Joint Forest Management (JFM)

The Joint Forest Management (JFM) approach, initiated in the 1990s and now supported under GIM and other MoEFCC schemes, has evolved into a cornerstone of community-led conservation. Over 100,000 JFM committees across 27 states manage more than 22 million hectares of forest land, combining local knowledge with state oversight.

Case study snippet: In Odisha’s Mayurbhanj district, JFM committees have turned degraded sal forests into thriving ecosystems, introducing sustainable harvesting practices for tendu leaves and medicinal plants. The model has since inspired similar community forestry efforts in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand.

Why this matters: JFM embodies inclusive climate governance ; decentralising forest management while creating income streams for marginalised groups, especially women. It strengthens both ecological resilience and social equity, a vital combination for India’s sustainability model.

Challenges: Weak legal status of JFM committees and unequal benefit-sharing mechanisms need reform to make community participation more meaningful and durable.

4. National Plan for Conservation of Aquatic Ecosystems (NPCA)

India’s freshwater and wetland systems are biodiversity hotspots but they face threats from urbanisation, pollution, and climate change. To counter this, the NPCA, launched in 2013, aims to conserve and manage wetlands and lakes through integrated approaches involving local bodies, scientific institutions, and state governments. (moef.gov.in)

Data highlight: By 2024, the NPCA had supported conservation of 180 wetlands and 65 major lakes across India. (pib.gov.in)

Case study snippet: The rejuvenation of Chilika Lake in Odisha, Asia’s largest brackish-water lagoon, under NPCA funding restored fish stocks by 15% and boosted local eco-tourism income by ₹150 crore annually.

Why this matters: Healthy wetlands are vital for climate adaptation, acting as buffers against floods and droughts while storing vast amounts of carbon. NPCA’s focus on local governance ensures ecological outcomes translate into community benefits — a key goal of sustainable finance frameworks.

5. Swachh and Smart Cities Mission: Solid Waste Management Component

Often overlooked within the broader Smart Cities framework, the Solid Waste Management (SWM) component has become a key lever for India’s circular economy. The mission promotes source segregation, waste-to-energy plants, and decentralised composting in cities. (swachhbharaturban.gov.in)

Data highlight: As of mid-2024, 96% of India’s 4,400+ urban local bodies were practising waste segregation at source, up from just 18% in 2014. Over 210 waste-to-energy facilities are either operational or under construction. (mohua.gov.in)

Case study snippet: Indore’s integrated SWM system combining door-to-door waste collection, composting, and recycling has become a model for sustainable urban management. The city now diverts over 90% of its solid waste from landfills and generates biogas for municipal vehicles.

Why this matters: The SWM component translates circular economy principles into action, reducing landfill emissions, conserving resources, and creating green jobs. It also attracts ESG-aligned investment, as municipal waste systems are emerging sectors for green bonds in India.

The Ecological Bottom Line

From forests to wetlands, India’s ecological schemes reflect a profound recognition: natural capital is national capital. The Green India Mission’s forest restoration, NPCA’s wetland rejuvenation, and Smart Cities’ waste circularity all converge toward one outcome ; a resilient, low-carbon, and biodiverse India.

Yet, experts warn that success hinges on consistent financing, transparent data, and local participation. As climate risks intensify, aligning ecosystem protection with climate finance will be essential not just for carbon sequestration, but for water security, food resilience, and public health.

India’s future sustainability will depend on how effectively it bridges policy ambition and ecological action, ensuring that every rupee of public and private green investment strengthens both the economy and the environment.

Challenges, Gaps & Future Outlook

This section functions as the analytical heart of the piece : assessing where India’s sustainability schemes stand today, what structural barriers persist, and what strategic shifts are needed to scale them into a greener and more equitable future.

It maintains the editorial clarity, research grounding, and SEO-optimized readability you requested earlier.

Challenges, Gaps & Future Outlook

India’s sustainability narrative is bold , but the transition to a low-carbon, inclusive economy remains a complex, multi-decade undertaking. While government schemes such as the National Solar Mission, Swachh Bharat Mission, and Green India Mission have achieved measurable progress, scaling them into systemic transformation requires addressing critical gaps in financing, governance, data transparency, and capacity building.

1. Implementation Bottlenecks and Institutional Silos

Many sustainability schemes operate under separate ministries, often with overlapping goals but limited coordination. For example, water conservation under the National Water Mission overlaps with agriculture-focused initiatives like PM-KUSUM and NMSA, yet data and resource sharing remain fragmented.

According to the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report (2023), less than 60% of climate-related projects met their stated milestones due to delays in fund release, tendering issues, and lack of inter-ministerial synergy. (cag.gov.in)

Case in point: Several Smart Cities projects faced execution delays because of unclear coordination between local bodies, state utilities, and central agencies. The same applies to solar park installations, where land acquisition and grid-integration hurdles slowed progress.

This institutional silo effect not only hampers timely delivery but also weakens impact measurement. Sustainability demands integration between ministries, between the centre and states, and between data systems that track water, energy, waste, and emissions collectively.

2. Financing the Green Transition

The economic case for sustainability is clear: India needs an estimated $10 trillion in cumulative investments by 2070 to reach net-zero emissions. (IEA, 2024)

However, domestic green finance flows remain limited only about 10–12% of the required annual investment is currently being mobilised. (RBI Bulletin, 2023)

Government schemes such as PM-KUSUM and AMRUT rely heavily on budgetary allocations. Yet the fiscal space is tightening, prompting a shift toward blended finance models , combining public subsidies with private capital and international climate funds.

India’s financial regulators have begun responding:

- The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued its first framework for green deposits in 2023.

- The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) launched disclosure norms for ESG funds, improving transparency.

- The government’s issuance of sovereign green bonds worth ₹16,000 crore in FY2023–24 signaled investor appetite for sustainable assets.

The challenge now lies in deepening financial innovation, enabling smaller projects, municipalities, and MSMEs to access climate finance through simplified credit mechanisms and guarantees.

3. Data, Monitoring, and Accountability

Sustainability thrives on data, but India’s monitoring architecture remains uneven. Many schemes report inputs (spending, construction) rather than outcomes (impact, emissions reduction, health gains).

For instance, while the Jal Jeevan Mission tracks tap connections, it lacks comprehensive data on water quality, groundwater recharge, or long-term functionality. Similarly, UJALA’s energy savings are well-documented, but lifecycle waste data for LED disposal remain sparse.

The NITI Aayog’s SDG India Index (2023–24) has improved transparency by providing state-level performance metrics, yet independent verification and localised data remain inconsistent. (niti.gov.in)

Experts recommend creating a National Sustainability Dashboard, integrating environmental, social, and financial indicators across ministries. This would enable real-time tracking of the country’s progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and ensure data-driven decision-making.

4. Technological and Capacity Barriers

While India has demonstrated global leadership in solar and digital infrastructure, the technical skill gap in sustainable project design and monitoring persists. Many state departments and local bodies still lack engineers trained in renewable systems, circular economy logistics, or carbon accounting.

According to a World Bank study (2024), only 38% of urban local bodies had access to full-time environmental engineers, and fewer than half used geospatial tools for waste and water management.

Addressing this gap requires institutional reform: dedicated sustainability cells in state departments, technical assistance hubs for municipalities, and vocational training for green jobs under the Skill India Mission.

5. Behavioural and Social Dimensions

Policy can build infrastructure but sustainability ultimately hinges on human behaviour. Schemes like Swachh Bharat and PM Surya Ghar rely on public participation, yet maintaining behavioural change is complex.

For example, while rural toilet construction under SBM exceeded targets, regular usage rates in some districts fell below 80%. Similarly, several rural households equipped with rooftop solar systems remain grid-dependent due to cultural and technical unfamiliarity.

Social inclusion is another dimension: sustainability programmes must integrate women, tribal, and marginalised communities not just as beneficiaries but as co-creators of change. Successful models like women-led water committees under the Jal Jeevan Mission prove that local leadership can multiply impact.

6. Global Integration and Carbon Markets

India’s domestic schemes increasingly align with international sustainability frameworks. The country’s participation in the Paris Agreement, the International Solar Alliance (ISA), and COP28 carbon-market negotiations reflects this growing global leadership.

Yet participation in carbon markets remains cautious. While India authorised Article 6.2 trading under the Paris framework in 2023, the domestic carbon-credit registry is still evolving. Once operational, it could unlock billions in private climate finance for renewable, forest, and efficiency projects. (moef.gov.in)

The challenge lies in balancing export-oriented carbon trading with domestic sustainability priorities, ensuring environmental integrity and equitable benefit-sharing.

7. The Road Ahead: Scaling from Schemes to Systems

India’s next sustainability frontier lies not in launching more schemes, but in integrating existing ones into unified systems that deliver measurable, long-term resilience.

This means:

- Linking water, energy, and land policies under a single resource-governance framework.

- Designing “green public investment plans” that align annual budgets with carbon-reduction trajectories.

- Expanding public-private partnerships (PPPs) for smart infrastructure, green manufacturing, and clean mobility.

- Building robust impact evaluation frameworks to measure co-benefits like gender equity, job creation, and biodiversity gains.

With more than 30 government schemes already aligned to the SDGs, India has the policy infrastructure in place. What it needs next is convergence, accountability, and scale ; the ability to make each rupee of investment count twice: once for growth and once for sustainability.

8. Future Outlook: Toward a Climate-Resilient India

India’s sustainability story is entering its decisive decade. By 2030, the country aims to:

- Generate 50% of its electricity from renewables.

- Achieve universal water and sanitation access.

- Plant 5 million hectares of new forest cover.

- Reduce emission intensity of GDP by 45% from 2005 levels.

These goals are ambitious yet achievable, provided India bridges policy execution with innovation and finance.

In the words of the UN Resident Coordinator in India, “Sustainability in India is not just about climate; it’s about inclusion, innovation, and intergenerational justice.”

If government schemes continue to evolve as ecosystems not silos; India could very well redefine what “green growth” means for the Global South: not a compromise between development and environment, but a convergence of the two.

Conclusion: Path Forward & What’s at Stake

India’s sustainability journey has entered a decisive decade ; one defined by the need to turn ambition into measurable action. With over 30 flagship schemes spanning renewable energy, water, sanitation, agriculture, and green industry, the country has built a powerful framework for inclusive, low-carbon growth. The path forward lies in scaling what works, aligning policy and finance, and empowering states and communities to lead. Success will depend on transparent data, steady investment, and citizen participation. If India can transform these programs from isolated schemes into a unified system of sustainable governance, it will not only meet its net-zero 2070 and SDG 2030 goals but also redefine global development, proving that economic progress and environmental stewardship can thrive together.

FAQs: India’s Sustainability Push: 30 Government Schemes Driving Green Growth

What are India’s main government schemes that promote sustainability?

India has launched over 30 national-level schemes that promote sustainability across renewable energy, water management, sustainable agriculture, waste reduction, and biodiversity conservation including the National Solar Mission, Jal Jeevan Mission, Swachh Bharat Mission, and Green India Mission.

How do these schemes align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

NITI Aayog has mapped each major scheme to specific SDGs such as Clean Water and Sanitation (SDG 6), Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 7), and Climate Action (SDG 13), ensuring that India’s domestic policies directly contribute to global sustainability targets.

What role does the Jal Jeevan Mission play in sustainability?

The Jal Jeevan Mission focuses on providing safe, piped drinking water to every rural household while improving groundwater management and sanitation. It strengthens water security and promotes equitable access to a basic human need.

How does the Swachh Bharat Mission support environmental health?

Swachh Bharat has drastically improved sanitation infrastructure and reduced open defecation, leading to better public health, cleaner water sources, and reduced methane emissions from waste.

Why is renewable energy central to India’s green growth agenda?

Renewable energy through schemes like the National Solar Mission, PM-KUSUM, and the Green Hydrogen Mission helps reduce dependence on fossil fuels, cut emissions, and attract green investments while powering inclusive development.

What is the significance of the PM-KUSUM scheme?

PM-KUSUM supports farmers by solarising irrigation pumps and promoting decentralized clean power generation, reducing diesel use and lowering costs for rural communities.

How does the Smart Cities Mission contribute to sustainability?

The Smart Cities Mission enhances urban resilience through energy-efficient infrastructure, clean transport, digital governance, and sustainable waste management systems in over 100 Indian cities.

What is AMRUT 2.0, and how does it differ from the first phase?

AMRUT 2.0 expands the first phase’s focus on water supply and sewerage systems to include universal tap connections, green spaces, and urban climate adaptation across 4,700+ towns.

Why is energy efficiency a recurring theme across multiple schemes?

Energy efficiency reduces both emissions and costs. Programmes like UJALA, ECBC, and BEE’s Energy Audit Scheme save millions of megawatt-hours annually, lowering the energy intensity of India’s GDP.

What does the Green Hydrogen Mission aim to achieve?

It seeks to make India a global hub for producing and exporting green hydrogen; an essential step toward decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors like steel, cement, and fertilisers.

How does the Green India Mission support climate goals?

The mission restores degraded forests and enhances carbon sinks, supporting both biodiversity conservation and India’s commitment to absorb 2.5–3 billion tonnes of CO₂ by 2030.

What role do community-based programmes like Joint Forest Management play?

They empower local and tribal communities to co-manage forests, improving livelihoods while conserving ecosystems ; a cornerstone of India’s people-centered sustainability model.

How does India integrate circular economy principles into its sustainability strategy?

Schemes under the Swachh Bharat and Smart Cities programmes encourage recycling, composting, and waste-to-energy projects, reducing landfill dependency and creating green jobs.

What financial mechanisms support these sustainability schemes?

India leverages public budgets, international climate funds, and green finance instruments such as sovereign green bonds, ESG funds, and blended finance models to sustain these programmes.

What challenges do these government schemes face?

Implementation delays, fragmented data systems, limited inter-ministerial coordination, and financing gaps are among the key challenges in scaling sustainability efforts nationwide.

How does the private sector contribute to India’s green growth journey?

Private investments in renewable energy, electric vehicles, and green manufacturing complement public programmes, driving innovation, efficiency, and employment in sustainable sectors.

What is the link between sustainability and job creation in India?

Schemes like PM-KUSUM, FAME India, and the Green Business Scheme generate thousands of green jobs in solar, EV, recycling, and agroforestry sectors, aligning economic growth with environmental protection.

How does India track its sustainability progress?

NITI Aayog’s annual SDG India Index and sector-specific dashboards monitor state-level progress, but experts call for unified, real-time sustainability data systems for greater accountability.

Why is India’s approach considered unique globally?

Unlike many nations, India embeds sustainability into welfare programmes, making climate action inseparable from poverty reduction, rural empowerment, and infrastructure growth.

What is the long-term outlook for India’s sustainability journey?

If existing schemes are scaled effectively and integrated through strong governance and finance, India is poised to meet its 2030 SDG commitments and its 2070 net-zero target; setting a global benchmark for equitable green growth.

Building India’s Sustainable Future, Together

India’s green transition is no longer the responsibility of government alone; it’s a collective mission that calls for participation from every citizen, business, and policymaker. The 30 sustainability schemes highlighted in this article are not abstract policies; they are living opportunities to reshape how India grows, consumes, and conserves.

As the country races toward its Net Zero 2070 and SDG 2030 goals, your role matters. Support renewable energy adoption in your home, conserve water, segregate waste, choose eco-friendly products, and demand transparency in sustainability reporting from businesses and leaders. Every local action contributes to national resilience.

India has shown that sustainability and development are not opposing forces; they are two sides of the same future. The time to act is now. Whether you are a student, entrepreneur, or policymaker, be part of India’s journey toward a cleaner, smarter, and more inclusive tomorrow.

Authored by- Sneha Reji