Problem Statement & Why It Matters

In cities across the globe, rivers once celebrated as lifelines of human civilization are now choked by plastic waste, transforming vibrant urban waterways into corridors of environmental peril. According to a growing body of research, over a thousand rivers account for nearly 80 percent of plastic debris flowing into the world’s oceans, with a handful of populous urban rivers—many in Asia and Africa—emerging as the most prolific conduits of this pollution.

This staggering reality underscores that plastic-free rivers are not a peripheral environmental ambition, but a central challenge for sustainability, public health, and climate resilience.

This article argues that the path toward zero-waste river cities lies in a circular economy blueprint—an integrated strategy that not only blocks or removes waste at the water’s edge but prevents its creation in the first place. The circular economy principles—“design out waste”, “keep materials in use”, and “regenerate natural systems”—offer a life-cycle framework.

Imagine urban designers collaborating across industries to redesign packaging; imagine community-run river-bank recovery units powered by solar energy, paired with local upcycling workshops; imagine fine-tuned monitoring systems that not only count particles but also guide actions and policy. These are not abstract dreams—they are unfolding prototypes in cities like Mumbai and Dehradun.

In essence, rivers mirror the health of their cities. To restore them, we must shift from reactive cleanup to preventive, systemic transformations—a shift that is captured in the electric promise of a circular economy. This article delves into the science of plastic flux, the technological solutions, the behavioral drivers, and the policy scaffolds necessary to chart a credible course toward plastic-free rivers.

How Plastics Flow from City to River to Ocean — The Science

In a city, a rainstorm doesn’t just wash streets clean—it sweeps up millions of fragments of plastic, from tire dust and synthetic fibers to degraded packaging, sending them directly into storm drains and rivers. These rivers, often seen as lifelines of urban life, become conveyor belts for plastic debris that eventually ends up in our oceans. Studies reveal that transport pathways include fragmentation of larger plastics, urban runoff, wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluent, and even atmospheric deposition—tiny particles carried by air settling into rivers and lakes.

What makes the situation direr is how plastic behaves in the environment. Rather than breaking down harmlessly, plastics fragment into microplastics—particles under 5 mm that persist in water, sediment, and even the air. These fragments float, often getting ingested by filter feeders like zooplankton, then climbing up the food chain. Researchers employ methods such as transect sampling, sieving, spectroscopic polymer identification (FTIR), and reporting metrics like particle count or mass per area—though a lack of standardization still clouds the comparability of studies.

Yet it is the less visible impacts that are most alarming. Microplastics are not inert—they adsorb toxic chemicals like bisphenol A and phthalates, and often carry harmful metals or pathogens into aquatic systems. In freshwater ecosystems, this can manifest in multiple ways: from oxidative stress in fish to damage to their immune systems, reduced reproductive output, and even neurotoxicity.

These ecological harms ripple into our own lives. Humans are exposed to microplastics through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact, with particles found in blood, organs, and even brain tissue. Emerging research links this exposure with inflammation, endocrine disruption, digestive and reproductive health impacts, and neurotoxicity—though long-term epidemiological data remains sparse.

To make sense of this complex challenge, scientists are calling for standardized monitoring protocols, expanded baseline measurements, and better interdisciplinary collaboration—acknowledging that without harmonized methods, we’re piecing together a jigsaw with missing and mismatched parts.

Why the Circular Economy is the Right Framework

For decades, our relationship with plastics has been locked in a linear economy model: extract fossil fuels, produce plastic, use it briefly, then discard it—often into landfills, incinerators, or the environment. This “take–make–dispose” system is fundamentally unsustainable, both ecologically and economically. The circular economy offers a profound alternative: a regenerative system designed to eliminate waste, keep materials in use, and restore natural ecosystems.

In a circular framework, plastics are not seen as disposable nuisances but as resources that retain value beyond a single life cycle. Instead of ending up in a river, a plastic bottle might be collected, reprocessed into a textile fiber, and eventually reused in new products. This approach reduces the demand for virgin plastics, cuts greenhouse gas emissions, and prevents the escape of debris into waterways. A 2021 UNEP report found that embracing circularity in plastics could reduce global plastic pollution by up to 80% by 2040, while generating significant economic and social benefits.

Scientific research supports this. Life-cycle assessments (LCAs) demonstrate that designing products for durability, repairability, and recyclability reduces environmental impacts across multiple categories—from carbon emissions to water use (ScienceDirect study). For instance, substituting single-use packaging with reusable systems not only lowers waste but also reduces overall resource consumption when paired with efficient logistics. This aligns with the waste hierarchy principle, which prioritizes prevention, followed by reuse, recycling, and energy recovery.

Urban rivers present an ideal testing ground for circular principles because they capture the interface between production, consumption, and waste leakage. By embedding circularity into urban planning, waste management, and product design, cities can intercept plastics before they enter waterways. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s New Plastics Economy initiative has shown that shifting to reusable packaging and ensuring all plastics are recyclable or compostable could transform the plastic system at scale—turning rivers from waste conduits into indicators of urban sustainability.

Real-world examples are already emerging. In Mumbai’s Mithi River project, recovered plastic is not merely discarded but transformed into marketable products through community-led upcycling enterprises. Similarly, in Amsterdam, a citywide circular economy plan integrates river cleanups with waste-to-resource strategies, creating jobs while cutting pollution. These cases prove that the circular economy is not a theoretical construct—it is a working model capable of producing measurable results.

At its core, the circular economy reframes the narrative: plastic is not an inevitable pollutant but a design challenge. When cities adopt this mindset, rivers stop being the endpoints of waste and become the starting points of regeneration. The blueprint for plastic-free rivers, therefore, is inseparable from the blueprint for a circular, zero-waste city.

The Technical & Scientific Toolbox for Plastic-Free Rivers

If the circular economy provides the blueprint for plastic-free rivers, then technology and science are the tools in the architect’s kit. Without them, even the most visionary plans remain sketches. Modern river protection demands a fusion of environmental engineering, ecological science, and community-level innovation, applied in a way that prevents, intercepts, and repurposes waste before it becomes an ecological hazard.

The first step is accurate monitoring and baseline assessment. Just as doctors rely on blood tests to diagnose disease, river managers use transect surveys, net sampling, and spectroscopic polymer identification (FTIR) to understand both the quantity and type of plastics in a waterway. Microplastic particles—often invisible to the naked eye—require sieving, filtration, and infrared analysis to distinguish between natural fibers and synthetic polymers. Without these diagnostics, interventions risk being misdirected or inefficient, like prescribing medication without knowing the illness.

On the engineering front, a new generation of plastic interception devices is redefining river cleanup. Floating barriers and booms stretch across sections of a river, guiding debris into collection points where it can be safely removed. Some systems are solar-powered and autonomous, reducing operational costs and carbon footprints. These devices are particularly effective in high-flow, high-pollution rivers, intercepting waste before it reaches estuaries or the ocean.

Alongside hardware, floating wetlands—constructed islands planted with vegetation—offer a hybrid solution. They not only trap floating debris but also provide habitat for wildlife and help remove excess nutrients from polluted water. This mirrors nature’s own cleansing processes, turning the riverbank into a living filter rather than a static barrier.

Decentralized recycling units represent another frontier. Instead of sending recovered waste to distant facilities, these units—often housed in shipping containers or small modular hubs—sort, shred, and remanufacture plastics locally. This approach closes the material loop, cuts transportation emissions, and often generates livelihoods through community-led micro-enterprises. Earth5R’s work along the Mithi River is a prime example, combining interception technology with local upcycling workshops that turn recovered plastics into products like furniture and building materials.

The scientific toolbox also extends to data platforms. Citizen science apps allow residents to log litter sightings, geo-tag pollution hotspots, and track cleanup events. When integrated with municipal systems, these datasets help authorities deploy resources where they are needed most, and allow researchers to evaluate the impact of interventions over time.

Finally, successful use of this toolbox requires iterative testing—just as scientists refine a hypothesis with each experiment, cities must refine their technologies based on measured results. In some cases, that means combining methods: interception booms to stop the macroplastics, coupled with wastewater treatment upgrades to reduce microplastics, and upstream policy changes to eliminate problematic packaging altogether.

In short, the technical and scientific arsenal for plastic-free rivers is already here—it’s the integration of these tools, guided by accurate data and community participation, that transforms isolated projects into systemic change. Without such integration, even the best technologies risk becoming well-intentioned but short-lived gadgets; with it, they become cornerstones of a resilient, circular urban water system.

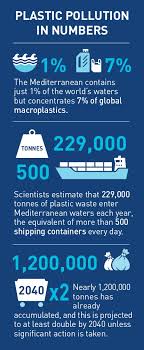

This infographic highlights the alarming scale of plastic pollution, with the Mediterranean holding just 1% of global waters yet 7% of macroplastics, and warns that accumulated waste could double by 2040 without urgent action. It underscores the critical need for circular economy strategies to protect river and marine ecosystems.

A Practical Blueprint — Circular Economy Interventions at City Scale

Cities aspiring to become zero-waste river communities must do more than clean up water—they must disrupt the system that allows plastics to flow from streets into rivers. A circular economy offers the framework, but it’s the interventions—from policy shifts to community action—that bring it to life. Here’s how cities can operationalize this blueprint at scale:

Source Reduction & Product Policy

Shifting the needle begins at the point of product design. Banning non-recyclable single-use plastics, enforcing extended producer responsibility (EPR), and incentivizing packaging redesign are key levers. A closed-loop policy framework encourages manufacturers to take back products, reducing waste and the risk of river-bound leakage. Science shows that such upstream interventions have outsized effects—targeting single-use items, the majority of which cannot be recycled efficiently, is critical to minimizing microplastic pollution.

Collection & Material-Level Circularity

A robust local collection system must be coupled with inclusive recycling economics. Cities can integrate informal waste pickers into formal supply chains via buy-back or aggregation centers, ensuring recovered waste remains a valuable asset rather than discarded. Earth5R’s programs train thousands—10,000 families and 500 businesses—to participate in circular systems, including composting and source separation, building behavioral change from the ground up.

River Interventions & Interception

Along the rivers themselves, interception technologies act as sentinel systems. Floating booms and solar-powered collection units act immediately, preventing plastic from reaching downstream. Mumbai’s Mithi River project, for instance, deployed a river-based collection unit, combined with chemical recycling, and trained households in surrounding neighborhoods to separate waste—bridging source reduction with recovery and reuse.

Value Chains & Upcycling

Cities must elevate recovered plastic into economic value. Earth5R’s Circular Cleanup Model transforms river waste into new materials and products—employing AI-driven sorting, sensor-supported categorization, and hands-on craftsmanship—to build circular supply chains out of what was once pollution. In doing so, communities turn waste into livelihoods and clean water into opportunity.

Monitoring, Evaluation & Transparency

All of these measures hinge on intelligent tracking. Pilot metrics might include reductions in plastic input (kg/day), recovered mass (tonnes/month), and the percentage reintegrated into recycled products. Frameworks like those advocated by the OECD help cities monitor progress, engage stakeholders, and refine actions using data—not guesswork.(OECD)

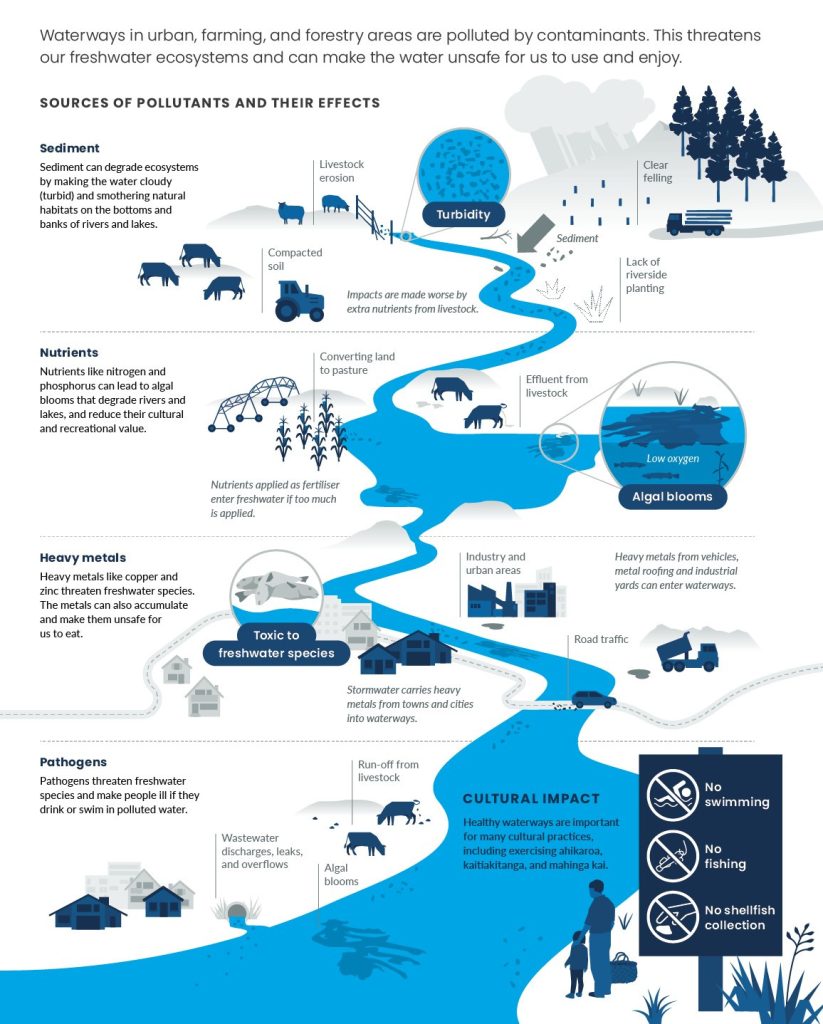

This infographic illustrates how pollutants like sediment, excess nutrients, and heavy metals enter waterways, causing turbidity, algal blooms, and toxic conditions for freshwater species. It emphasizes the urgent need for integrated circular economy solutions to prevent river ecosystem degradation.

Earth5R Case Studies: On-the-Ground Implementation of Plastic-Free River Strategies

In the battle against plastic pollution in rivers, few grassroots organizations have demonstrated the scale and adaptability of Earth5R. Founded with a mission to create zero-waste, sustainable cities, Earth5R has implemented community-driven, circular economy models that turn waste into a resource while empowering local livelihoods. Their river and lake restoration work is not just an environmental campaign—it’s an economic and social transformation blueprint that has inspired replication in multiple countries.

One of Earth5R’s most compelling models is its Blue Cities Program, which aims to create plastic-free urban water bodies through a combination of waste segregation, recycling, composting, and upcycling. In Mumbai, the project targeted river stretches and coastal areas clogged with single-use plastics, largely originating from informal settlements without proper waste management. Instead of relying solely on clean-up drives, Earth5R engaged residents through circular economy training sessions, teaching them to turn plastic waste into eco-bricks, handicrafts, or building materials. This not only reduced pollution but also created micro-entrepreneurship opportunities for women and unemployed youth.

In Pune, the organization collaborated with local authorities and schools to initiate zero-waste campus projects, integrating river-cleaning efforts into environmental education. By installing segregation bins along riverbanks, they ensured that plastic did not enter the water flow in the first place. Students became “river stewards,” conducting waste audits and mapping plastic hotspots—a model that mirrored successful community science initiatives seen in countries like the Netherlands’ Plastic Soup Foundation.

Internationally, Earth5R has extended its plastic-free strategies to Kenya, Colombia, and France, adapting its model to suit local contexts. For example, in Nairobi, waste pickers were trained to convert riverbank plastics into marketable products, creating a self-sustaining incentive to keep waterways clean. This mirrors findings from a 2019 UNEP report, which stresses that without economic incentives, anti-plastic campaigns rarely achieve long-term success.

Perhaps the most striking feature of Earth5R’s work is its integration of environmental restoration with social justice. By involving marginalized communities directly in the circular economy, they’ve transformed what was once seen as a municipal waste problem into a community-owned resource loop. The results are tangible: cleaner rivers, reduced landfill dependency, revived biodiversity, and increased household incomes.

As the world looks for scalable, science-backed solutions to the river plastic crisis, the Earth5R model stands out as a proof of concept—showing that the circular economy is not just theory but a real, replicable pathway to zero-waste river cities.

Policy, Financing & Governance Enablers

To scale the success of Earth5R’s on-the-ground circular economy efforts, policy frameworks, innovative finance, and enabling governance structures are essential. Local leaders must weave together regulatory incentives, public–private–community partnerships, and sustainable funding mechanisms to elevate grassroots successes into city-wide transformations.

Policy Tools and Multi-Stakeholder Governance

Cities and regions are uniquely positioned to champion circular-water innovation. According to the OECD, local governments are pivotal in executing circular economy transitions across vital areas such as solid waste, water management, land use, and climate strategy—making them natural incubators for plastic-free river initiatives (OECD). Governments can activate policies like Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), packaging bans, or streamlining permitting for recycling ventures—all designed to align material flows with circular outcomes.

Earth5R’s approach illustrates effective multistakeholder governance. Their initiatives—from the Blue Cities Program to Mumbai’s Mithi River cleanups—embody a Public-Private-Community Partnership (PPCP) model that blends citizen action with scientific monitoring and institutional support. Such governance frameworks encourage co-ownership of outcomes while enabling scalable collaboration across society.

Financing Instruments for Circular River Restoration

Beyond policy, cities need novel and flexible funding sources to support both infrastructure and behavior change. Organizations like the Catalytic Finance Foundation (formerly R20) exemplify how subnational governments, NGOs, and funders can unite to finance green, climate-resilient infrastructure. In the water sector, the U.S. Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) provides long-term financing for water projects and could serve as an inspiration or blueprint for similar schemes in the Global South.

More aligned with circular economy goals, funding models such as environmental impact bonds, pooled municipal financing, or green bonds offer outcome-based investment with incentives for measurable environmental improvements. These instruments can be deployed to support river cleanup infrastructure, circular waste processing hubs, and urban recycling enterprises.

Leveraging Financial Innovation and Private Engagement

Cities can also attract private capital through blended finance strategies that combine public, philanthropic, and commercial investments—especially in circular pilot projects with strong social co-benefits. Further, market tools like green rating systems, insurance instruments penalizing pollution, and carbon pricing can disincentivize waste-intensive practices and channel capital toward cleaner alternatives.

Earth5R’s Real-Time Monitoring as Governance Enabler

Earth5R underlines the power of transparency in catalyzing trust and scaling interventions. Their real-time impact monitoring system, powered by mobile tech and community reporting, ensures that waste removal metrics, water quality, and volunteer mobilization are publicly visible—an essential foundation for accountability and adaptive governance (Earth5R).

Metrics of Success & Recommended Monitoring Framework

When aiming to transform rivers into zero-waste arteries within a circular economy framework, what gets measured gets managed. Without clear indicators and systematic monitoring, even well-designed interventions can drift into guesswork. Here’s how cities and projects like Earth5R are building robust, data-driven metrics pipelines to measure what matters—and ensure long-term success.

Defining Clear KPIs for River-Circularity Integration

At Earth5R’s Mithi River cleanup, project leaders tracked multiple metrics: the volume of waste removed, improvements in water-quality parameters, and observable recovery in biodiversity along the riverbank. In its first phase, teams removed over 250 metric tons of waste across nearly 8 km of river stretch—a tangible milestone that anchors the program’s impact in reality.(Earth5R)

Beyond localized examples, the Clean River Model—a holistic circular economy strategy being validated across rivers in Belgium, Indonesia, and Cameroon—places KPI tracking and baseline evaluation at its core. This model aims to expand to 1,000 rivers by 2050, with measurable indicators guiding every phase.

Recommended KPI Categories & Monitoring Framework

Drawing from both practice and literature, the following KPI clusters provide a governance-ready structure:

- Pollution Flux & Recovery Metrics

- Mass of plastic removed (kg or tonnes per month)

- Plastic concentration reductions (mass or particle counts per m² or m³) at intervention hotspots

- Mass of plastic removed (kg or tonnes per month)

- Circular Economy Measures

- Percentage of recovered material re-entering formal recycling or upcycling

- Resource productivity or recovery rates, aligning with circular metrics frameworks from industry research

- Percentage of recovered material re-entering formal recycling or upcycling

- Ecosystem and Water Health Indicators

- Changes in water-quality parameters like turbidity, dissolved oxygen, or nutrient levels (e.g., pH, BOD)

- Biodiversity resurgence, via biological indicators or sentinel species (akin to the Mussel Watch Program)

- Changes in water-quality parameters like turbidity, dissolved oxygen, or nutrient levels (e.g., pH, BOD)

- Participatory & Transparency Metrics

- Citizen science contributions: number of volunteers, geo-tagged litter reports, app submissions (models like the UK’s River Trust Big River Watch illustrate scale)

- Frequency and quality of reporting back to the public—including dashboards, maps, and stakeholder briefings

- Citizen science contributions: number of volunteers, geo-tagged litter reports, app submissions (models like the UK’s River Trust Big River Watch illustrate scale)

- Baseline Comparison & Trend Tracking

- Establishing pre-intervention baselines to compare against ongoing data

- Use of standardized monitoring protocols—for example, the frameworks developed under UNEP guidelines or the harmonized monitoring workflow built for river plastics’

- Establishing pre-intervention baselines to compare against ongoing data

Rivers as Mirrors of Urban Health: From Pollution to Possibility

In the quest for plastic-free rivers, we’ve walked through the science of pollution, navigated the promise of circular economy strategies, and observed emerging success stories—from Earth5R’s innovation along the Mithi River to global tech like The Ocean Cleanup’s Interceptor system. The story now comes full circle with a powerful imperative: action at scale, rooted in the express simplicity of the water systems we depend on.

Rivers are not passive victims—they are active indicators of urban health. Each floating fragment, each microplastic particle, signals deeper failures in design, governance, and consumption. But, equally, each recovered bottle, each ton of diverted plastic, speaks volumes about the possibility of transformation. As The Ocean Cleanup’s 30 Cities Program aims to cut one-third of river plastic emissions by plugging critical urban leaks, it shows what coordinated, scaled action looks like in practice.

Equally inspiring is the rise of collaborative platforms like Earth5R’s BlueCities Network, which unites service providers, researchers, city officials, and grassroots leaders to co-create regenerative ecosystems in river cities. In cities across India, in global pilot sites, and increasingly even beyond, communities are demonstrating that rivers can be guardians of prosperity—not garbage.

Now is the moment for cities, corporations, policymakers, researchers, and everyday citizens to embrace this blueprint with urgency.

FAQs On Plastic-Free Rivers: The Circular Economy Blueprint Driving Zero-Waste River Cities

What is the concept of plastic-free rivers?

Plastic-free rivers refer to freshwater systems where plastic waste—both macroplastics and microplastics—is effectively eliminated through prevention, collection, recycling, and circular economy measures, ensuring healthy ecosystems and safe water for communities.

Why are rivers crucial in tackling plastic pollution?

Rivers act as the primary pathways that carry plastic waste from land to the ocean. Studies estimate that up to 80% of marine plastic pollution originates from river systems, making them critical intervention points.

What is the circular economy in relation to river management?

The circular economy promotes a system where resources are reused, recycled, or repurposed, preventing plastic from entering rivers in the first place while ensuring waste management infrastructure supports zero-waste goals.

How does plastic pollution affect river ecosystems?

Plastics block sunlight, reduce oxygen levels, and release harmful chemicals, disrupting aquatic life cycles. Microplastics are ingested by fish and enter the food chain, posing health risks to both animals and humans.

Can circular economy models eliminate river plastic entirely?

While complete elimination is challenging, circular economy strategies—including upstream waste reduction, extended producer responsibility (EPR), and waste-to-value innovations—can drastically reduce plastic inflow into rivers.

What are some common sources of river plastic pollution?

Mismanaged municipal waste, industrial discharges, inadequate sewage treatment, littering, and stormwater runoff are the most common contributors.

How can citizen participation help in achieving plastic-free rivers?

Citizen-led river cleanups, waste segregation at the household level, and participation in recycling programs amplify governmental and NGO efforts, fostering community ownership.

Are there examples of cities achieving zero-waste rivers?

Yes, initiatives in places like Amsterdam and Seoul have shown measurable success in drastically reducing river plastic through waste capture technology, strict regulations, and public engagement.

What role do policies and regulations play in this effort?

Strict bans on single-use plastics, mandatory waste segregation, EPR schemes, and penalties for illegal dumping form the backbone of successful river protection policies.

How do microplastics enter river systems?

Microplastics come from larger plastic items breaking down, microbeads in cosmetics, synthetic fibers from laundry, and tire wear particles washing into rivers via runoff.

What technological solutions are used to clean rivers?

Examples include interceptor barges by The Ocean Cleanup, floating trash barriers, AI-enabled sorting systems, and bioengineering solutions like constructed wetlands.

Can river restoration projects boost local economies?

Yes, restored rivers often lead to increased tourism, fishing opportunities, and improved public health, reducing long-term municipal costs.

What is the role of education in preventing plastic river pollution?

Educational campaigns help communities understand the consequences of river pollution, fostering behavioral changes that support sustainable waste practices.

How do Earth5R case studies contribute to this field?

Earth5R has implemented grassroots projects in cities like Mumbai, where waste is segregated at source, informal waste workers are integrated into the circular economy, and communities are empowered to maintain clean riverbanks.

What impact does plastic pollution have on human health?

Microplastics in rivers can contaminate drinking water and food sources, potentially leading to endocrine disruption, organ damage, and other health risks.

Is biodegradable plastic a viable solution for rivers?

While biodegradable plastics can reduce long-term pollution, they still require proper disposal conditions and should not replace reduction and reuse strategies.

How do global agreements address river plastic pollution?

International efforts like the UNEP Global Plastic Treaty aim to establish legally binding commitments for reducing plastic waste leakage into water systems.

What are some nature-based solutions for plastic-free rivers?

Riparian buffer zones, constructed wetlands, and mangrove restoration can trap waste before it enters rivers while also improving biodiversity.

How do informal waste workers contribute to river cleanliness?

Informal waste workers often collect, sort, and recycle waste before it reaches rivers, playing a critical role in the local circular economy.

What are the biggest challenges in implementing zero-waste river cities?

Challenges include insufficient funding, lack of public awareness, weak enforcement of waste laws, and limited infrastructure for waste collection and recycling.

Turning the Tide: A Collective Blueprint for Plastic-Free Rivers

Progress toward plastic-free rivers may come as governments consider circular economy strategies with clear goals, while industries and entrepreneurs explore partnerships to scale upcycling and innovative recycling solutions. Citizen scientists and educators can foster awareness and transparency through community-driven data and river audits, as philanthropies and international organizations support initiatives like Earth5R’s BlueCities and The Ocean Cleanup to expand successful models. Ultimately, cleaning rivers transcends debris removal—it embodies transforming hope into action and restoring rivers as vital urban lifelines. As rivers flow, so might our shared commitment to prevent, intercept, regenerate, and renew until waters run clear once more.

-Authored By Pragna Chakraborty