Why PPPs Matter in Agriculture Transition

India’s agriculture is undergoing a shift toward sustainability, driven by the need to combat soil degradation, climate risks, and declining farm incomes. Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) enable shared solutions that combine government policies with private innovation. They offer integrated frameworks for scaling organic farming.

Farmers face barriers in accessing markets, finance, and training. PPPs help by pooling resources from corporates, government, and NGOs. Through these alliances, farmers benefit from certification support, better logistics, and long-term sustainability.

Unlike isolated schemes, PPPs promote multi-stakeholder governance. This ensures participation from FPOs, academia, and tech startups. They build adaptable models aligned with India’s agro-climatic zones, improving both scale and efficiency. These partnerships foster innovation and inclusive growth.

PPPs play a key role in climate-resilient farming. By promoting organic inputs, water efficiency, and soil carbon practices, they enable regenerative outcomes. Digital tools and traceability systems make transitions more transparent. This also opens up access to green finance.

Farmers gain confidence when included as equal stakeholders in PPPs. Local co-design, language-based training, and feedback systems build trust. NGOs ensure ethical engagement, while corporates bring real-time market insights. The result is ownership, not just compliance, from farming communities.

Global examples like AGRA in Africa and EIP-AGRI in Europe show the strength of PPPs in agri-transformation. In India, think tanks like ICRIER and NITI Aayog support PPP models in organics. With a clear policy roadmap and stakeholder alignment, these partnerships can drive long-term impact.

Government-Led Projects: Strengths and Gaps

India has launched several flagship organic initiatives like Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY), Mission Organic Value Chain Development for North East Region (MOVCDNER), and National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture. These programs offer input subsidies, training support, and certification access. With vast outreach potential, they act as catalysts in scaling organic clusters across states.

Government schemes ensure policy continuity, rural employment, and financial backing for organic transition. Their structure integrates agricultural universities and Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) for technical support. Infrastructure like soil health cards and organic input centers strengthen their implementation base. This institutional ecosystem provides a strong foundation.

Despite scale, these projects face bureaucratic delays, poor last-mile delivery, and low farmer awareness. Fund disbursal is often delayed, impacting timely input procurement. Monitoring mechanisms remain weak due to limited digital infrastructure. These gaps dilute intended impact and disincentivize farmer participation.

Government-led models sometimes suffer from top-down planning that ignores local context. Uniform schemes across diverse agro-ecologies often fail to meet region-specific needs. Without feedback loops, farmers are treated as passive beneficiaries. This hampers ownership and limits innovation. Moreover, inter-departmental coordination remains weak, causing policy fragmentation.

There’s a lack of market linkage strategies within government-only organic projects. Most programs focus on production, neglecting post-harvest logistics and consumer access. This results in surplus without demand. Schemes rarely integrate traceability systems or branding support, keeping farmers out of premium markets. Consequently, financial returns remain limited.

For improvement, government programs must adopt PPP frameworks that include private logistics, digital traceability, and community engagement. Schemes should be co-designed with NGOs and FPOs to reflect real needs. Real-time data tools can improve accountability and impact monitoring. This evolution is critical for unlocking the full value of public investment in organic farming.

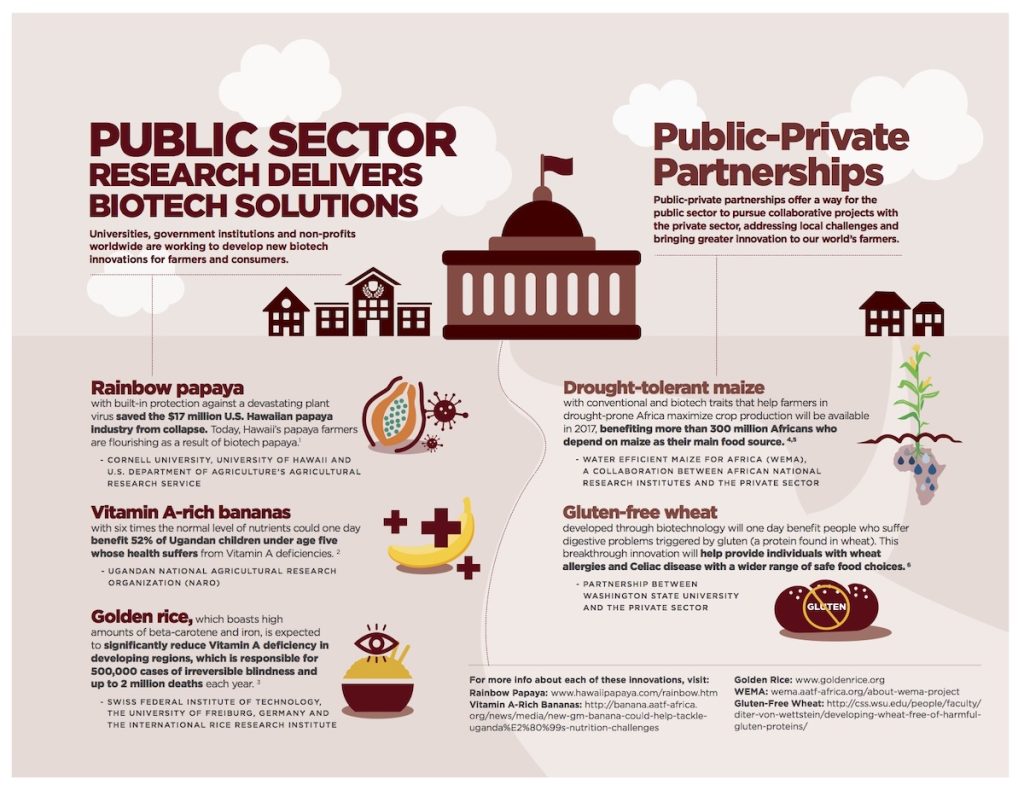

This infographic showcases how public–private partnerships drive biotech innovation in agriculture, highlighting solutions like drought-tolerant maize and vitamin-rich crops. It emphasizes the role of collaboration in addressing food security and nutrition challenges globally.

Corporate-Led Pilots: Speed, Risk, and Innovation

Private-sector pilots in organic farming, led by firms like ITC, Tata Chemicals, and Mahindra Agribusiness, bring speed and scalability to rural transitions. These models use contract farming, tech integration, and market incentives to build trust with farmers. Companies invest in input distribution and output procurement systems that cut inefficiencies.

These pilots often partner with FPOs, NGOs, and startups to ensure grassroots engagement. Their agility allows quicker rollout of organic certifications, field demonstrations, and consumer traceability. By deploying mobile tech platforms, they reduce reliance on traditional extension systems. This leads to wider outreach and improved adoption rates.

Corporate pilots introduce risk-sharing models that reduce farmer vulnerability. These include minimum support prices, crop insurance integration, and buy-back arrangements. Such measures ensure steady income during the transition to organic. Firms also provide certified bio-inputs to improve yield consistency. These financial tools foster confidence among smallholders.

Yet, corporate-led models can carry risks of exclusion and short-termism. Many pilots prioritize export markets over local food security. Projects may focus on high-margin crops, ignoring smallholder diversity. Limited transparency in contracts and data ownership may also create distrust.

Innovation is a core advantage of corporate pilots. Through blockchain systems, IoT-enabled farming, and remote sensing, firms offer next-gen tools to organic farmers. These technologies improve resource efficiency, soil monitoring, and real-time alerts. When scaled responsibly, these innovations can redefine rural agriculture.

To ensure sustainability, corporate-led pilots must align with public policy, ethical practices, and community benefits. Collaborative planning with state governments, local panchayats, and extension agencies ensures scale and accountability. Companies must focus on long-term investment, not pilot optics. True success lies in inclusive, farmer-centered growth.

Role of NGOs and Knowledge Partners

NGOs play a vital role in mobilizing rural communities, offering deep grassroots connections often absent in top-down schemes. They help build farmer trust and create awareness about organic practices. Their localized efforts promote inclusive participation, especially among marginalized groups. NGOs also bridge cultural and language gaps often missed in national rollouts.

Knowledge partners such as ICAR, FAO, and agricultural universities offer science-backed support in organic transitions. Their role includes curriculum design, soil health research, and field testing of organic methods. Institutions like IARI also facilitate organic input validation. This ensures that farmer training is backed by empirical knowledge.

Joint efforts between NGOs and academia create farmer field schools, peer-learning networks, and community training hubs. These systems promote adoption through demonstrations, language-accessible modules, and continuous mentoring. Models like Digital Green’s video-based learning show how tech-enabled NGOs can scale low-cost training effectively across states.

NGOs also support organic certification by helping farmers navigate Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) and third-party audits. They assist with recordkeeping, group formation, and monitoring standards. This reduces certification costs and ensures market credibility. NGOs act as mediators, protecting farmers from exploitative practices.

They also play a watchdog role in PPPs by ensuring ethical implementation and social accountability. In many cases, NGOs uncover data gaps, exclusion risks, and gender disparities in corporate projects. Their on-ground presence allows quick feedback and adaptive management. This makes them essential partners in ensuring PPP integrity.

To amplify impact, NGOs and knowledge partners must be formally included in PPP frameworks. Government agencies should allocate space for civil society engagement and integrate research insights into planning. This creates multi-directional partnerships where farmers, scientists, and social workers co-create resilient, regenerative organic ecosystems

Case Study: Organic Clusters in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh’s organic transition is spearheaded by the Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) initiative, later rebranded as Andhra Pradesh Community Managed Natural Farming (APCNF). Managed by RySS, this program combines agroecological principles with community leadership. Supported by state funding and global donors, it is one of India’s most ambitious PPPs in agriculture.

The APCNF model is built around women self-help groups (SHGs), ensuring local governance and transparency. Farmers are trained through community resource persons (CRPs) and demonstration plots. NGOs like WWF-India and Digital Green amplify outreach via participatory training and tech. The program actively avoids chemical inputs, replacing them with bio-inputs.

The PPP framework integrates government policy, donor funding, and civil society in one coordinated structure. The World Bank provided USD 100 million to scale this effort. Digital platforms enable real-time monitoring and farmer progress tracking. This structure ensures outcome measurement beyond mere distribution of inputs.

Outcomes have been significant: soil health improved, water usage reduced by 30%, and incomes rose in multiple districts. Farmers reported fewer climate-related crop failures, and women became key drivers of rural decisions. The program enabled carbon sequestration and opened opportunities for green finance and carbon credits. These benefits were amplified through community ownership.

Unlike top-down models, APCNF’s success lies in participatory governance. Farmers choose techniques, lead planning processes, and track results using mobile dashboards. Feedback loops ensure adaptive learning while accountability is shared among stakeholders. This creates a decentralized model that evolves with community needs.

The APCNF experience is now a model for replication. Several Indian states and African governments have studied it for inspiration. Researchers from ICAR, IIM, and international agencies recommend its design for scalable organic farming. Its success proves how blended PPP models can deliver economic, environmental, and social returns—when farmer-led and ecosystem-based.

Pitfalls in Coordination and Implementation

One major issue in PPPs is fragmented coordination between government agencies, corporates, and NGOs. Overlapping mandates often lead to confusion in project execution. Many initiatives lack a unified governance structure, causing delays and inefficiencies. Without clear role definitions, even well-funded projects underperform.

Lack of a shared data ecosystem hinders real-time decision-making. Stakeholders often operate with incompatible platforms or restrict data sharing. This leads to duplicated work and incomplete farmer profiles. Without digital traceability systems, monitoring becomes unreliable, and transparency suffers.

Political turnover frequently disrupts continuity. Changes in local leadership or state governments can delay approvals and reduce accountability. Programs may be paused, redirected, or canceled, affecting farmer confidence. Without long-term institutional mechanisms, PPPs become vulnerable to political shifts. This limits scalability and deters private investment.

Another challenge is the absence of robust Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) frameworks. Many projects rely on output metrics like training numbers rather than impact indicators such as yield improvements or income growth. Lack of third-party audits and impact assessments makes evaluation weak. This hinders course correction and policy learning.

Conflicts also arise when private interests clash with community priorities. Corporates may prioritize exportable crops over food security, excluding smallholders from benefits. Without ethical safeguards, power imbalances can lead to exploitation. NGOs often struggle to intervene if excluded from contract design.

Lastly, many PPPs underestimate the complexity of farmer behavior. Adoption is not automatic; it requires trust-building, consistent support, and locally relevant solutions. Rigid models fail to adjust to agro-climatic diversity or traditional practices. Without bottom-up planning, even well-intentioned programs face resistance and low retention.

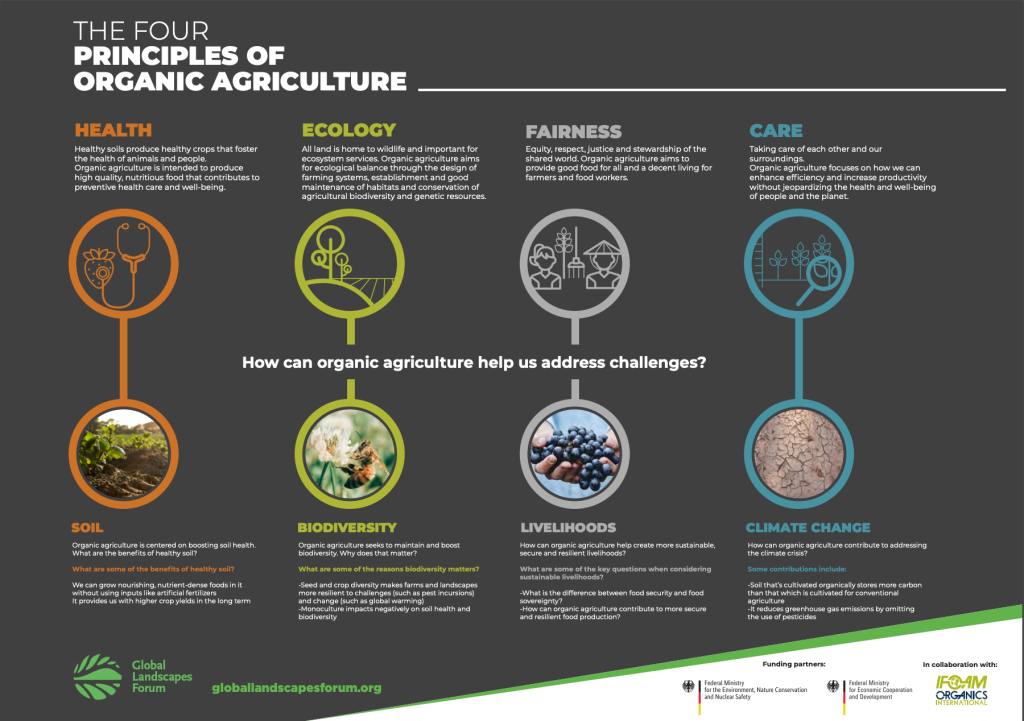

This infographic illustrates the four core principles of organic agriculture: Health, Ecology, Fairness, and Care. It highlights how these values address challenges like biodiversity loss, climate change, and sustainable livelihoods.

Financing the Transition through Joint Models

Transitioning to organic farming requires upfront investments in training, bio-inputs, and certification. For smallholders, these costs are often unaffordable without support. Blended finance models—combining government subsidies, CSR funds, and donor grants—help close this gap. Such integrated financing enables smoother adoption.

Public finance mechanisms like PKVY, MOVCDNER, and NABARD’s RIDF offer institutional support. These fund input subsidies, infrastructure creation, and group mobilization. However, such schemes often lack linkages with private marketing platforms or traceability systems, limiting their full financial potential.

Private players contribute by providing in-kind support, forward market contracts, and market access. Corporates can also fund capacity-building programs and digital infrastructure. Many include risk mitigation tools like crop insurance and price guarantees. These features make joint models attractive for farmers and ensure corporate responsibility.

Impact investors and ESG funds are showing interest in agroecological transitions. By linking PPPs with green finance instruments, there’s potential to unlock large-scale funding. Some states are exploring agriculture bonds and climate-linked lending to support organic farmers. This diversifies revenue sources and strengthens project sustainability.

An emerging opportunity lies in carbon markets, where farmers practicing organic methods contribute to carbon sequestration. Projects can monetize soil health improvements and reduced greenhouse emissions. Platforms like Verra and Gold Standard are now certifying agri-carbon offsets, allowing PPPs to access climate finance. This incentivizes both environmental and economic returns.

Financing success depends on well-defined PPP contracts, transparent revenue-sharing models, and clear risk allocation. Projects must ensure accountability mechanisms and equitable distribution of gains. Blended models should prioritize smallholder access and avoid elite capture. When structured ethically, joint financing can make organic farming both profitable and inclusive.

Bringing Digital Infrastructure into the Partnership

Digital tools are reshaping organic farming by enabling real-time monitoring, precision agriculture, and data-driven decisions. PPPs that incorporate remote sensing, GIS mapping, and IoT sensors can scale organic clusters faster. These technologies reduce dependency on field visits and offer efficiency at scale.

Platforms like CropIn, Agrivi, and Digital Green are empowering farmers through mobile-based training, farm logs, and advisory alerts. These solutions support organic traceability and ensure compliance with certification. Real-time weather, pest, and soil data allow precise interventions that protect crop quality and reduce input use.

One of the strongest cases for digital inclusion is traceability. Blockchain-backed systems guarantee farm-to-fork transparency, helping farmers command premium prices. Buyers can verify organic authenticity, boosting trust in both domestic and export markets. This opens pathways for global certifications and cross-border commerce.

Digital infrastructure also improves financial inclusion. Integration with direct benefit transfer (DBT), mobile wallets, and digital credit scoring makes it easier for farmers to access loans and subsidies. Tools like eNAM and AgriBazaar connect farmers directly to buyers, improving price realization. PPPs must leverage these systems to maximize economic impact.

Challenges remain around digital literacy, rural connectivity, and device access. Many farmers still lack smartphones or stable internet. Women and older farmers may need customized onboarding. NGOs can play a critical role in ensuring inclusive digital access and co-creating tools with communities. Without this, tech benefits remain unevenly distributed.

For long-term sustainability, PPPs should establish open digital ecosystems. This includes interoperable platforms, data-sharing protocols, and public-private data alliances. Government must invest in rural digital infrastructure and create policies that protect farmer data rights. Only then can digital infrastructure strengthen organic PPPs at scale.

Ensuring Farmer Trust and Participation

Farmer trust is the cornerstone of successful PPPs in organic farming. Projects must prioritize inclusivity, transparency, and mutual respect. Trust builds when farmers are treated as decision-makers, not passive beneficiaries. Co-designing models with community input enhances ownership and adoption.

Continuous engagement through farmer field schools, peer-learning, and demonstration plots reinforces participation. Extension workers and community resource persons (CRPs) act as trusted local advisors. Frequent interactions in local languages help demystify complex processes like organic certification.

Trust erodes when promises remain unmet. Delayed input delivery, poor price realization, and weak contract enforcement trigger dissatisfaction. Farmers also fear market volatility and loss of yield during transition. PPPs must establish grievance redressal and insurance support to mitigate these risks.

Ensuring participation requires acknowledging local knowledge systems. Traditional practices like mixed cropping, green manuring, and bio-pesticides must be integrated into modern approaches. Programs that dismiss such wisdom may face resistance. Respect for culture and agroecological diversity builds long-term loyalty.

Recognition and reward also enhance engagement. Linking farmers to premium markets, offering branding opportunities, and enabling export access builds pride in organic production. Celebrating local champions through awards and storytelling boosts morale and peer influence. When success is visible, participation becomes self-driven.

Lastly, trust thrives on transparency. Open communication of roles, responsibilities, and profit-sharing models ensures fairness. Digital tools for monitoring, feedback, and information access empower farmers to hold stakeholders accountable. When farmers feel heard and informed, participation becomes a natural outcome.

Frameworks for Long-Term PPP Success

A successful PPP in organic farming starts with a clear institutional framework. Roles of public agencies, private entities, and civil society must be defined upfront. This includes dispute resolution, decision-making authority, and reporting lines. A strong legal base ensures stability and fosters investor confidence.

Sustainable models require risk-sharing mechanisms. PPPs should build in minimum support prices, crop insurance, and price fluctuation buffers. This protects farmers during transition years and shields partners from unforeseen shocks. When risk is equitably distributed, partnerships endure beyond pilot stages.

A core pillar is an adaptive Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) system. Projects must track inputs, processes, and outcomes using digital dashboards. Third-party audits, farmer feedback, and geo-tagged evidence help ensure credibility. Transparency boosts both donor trust and farmer accountability.

Capacity-building must be institutionalized. Partnerships should include continuous training modules, curriculum development, and knowledge transfer platforms. Farmer producer organizations (FPOs), extension workers, and community trainers should be supported long term. Without this, institutional memory fades and scaling slows.

Financial frameworks should integrate blended capital, ESG investments, and climate-linked funds. These can be tied to measurable impact like soil health, carbon sequestration, or gender inclusion. Such alignment ensures long-term capital flow while advancing global goals like SDG 2.

Finally, partnerships must evolve. Long-term success depends on feedback loops, policy responsiveness, and community co-governance. Institutional structures should be nimble enough to absorb learnings and shift strategies. When PPPs are built as living systems, they grow stronger with time—and so does organic farming in India.

Conclusion: Public–Private Partnerships in Organic Farming: Models That Work and What to Avoid

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are emerging as powerful vehicles for accelerating India’s organic farming transition. By leveraging government support, private innovation, and community-led implementation, PPPs can bridge critical gaps in scale, financing, and outreach. However, success depends on models that prioritize farmer welfare, agroecological integrity, and inclusive growth.

Case studies like APCNF show that PPPs rooted in community ownership, supported by scientific institutions, and enabled through digital platforms can deliver long-lasting change. These models also open doors to climate finance, carbon markets, and global certification systems. More importantly, they empower smallholders to participate in sustainable agriculture.

But PPPs are not without pitfalls. Many suffer from poor coordination, data fragmentation, and top-down execution. Trust breaks down when farmers are excluded from decision-making or bear excessive risk. Hence, future partnerships must be anchored in transparency, shared accountability, and ethical practices.

To be future-ready, PPPs in organic farming must adopt open digital ecosystems, adaptive financing, and farmer-first governance. As India aims for soil health, climate resilience, and food security through agroecology, PPPs must become more than transactional—they must evolve into long-term ecosystems of shared purpose, prosperity, and participation.

Frequently Asked Questions: Public–Private Partnerships in Organic Farming: Models That Work and What to Avoid

What is a Public–Private Partnership (PPP) in organic farming?

A PPP in organic farming involves collaboration between government, private companies, NGOs, and communities to promote sustainable agriculture practices, share risks, and scale organic initiatives.

Why are PPPs important for India’s organic transition?

PPPs bring together public policy, private innovation, and grassroots mobilization, making them crucial for scaling organic farming and reaching smallholder farmers across diverse regions.

How do government-led PPPs support organic farming?

Governments offer subsidies, technical guidance, and certification support through schemes like PKVY and MOVCDNER, while also facilitating coordination among stakeholders.

What role do corporates play in organic PPPs?

Private companies contribute by offering market access, digital tools, premium pricing, and infrastructure for traceability, helping farmers improve profitability and sustainability.

Are there risks in corporate-led organic initiatives?

Yes, corporate projects may prioritize export crops over food security or exclude marginal farmers if not regulated through ethical, inclusive PPP frameworks.

How do NGOs strengthen PPPs in organic agriculture?

NGOs build trust with communities, conduct localized training, support certification, and ensure social equity, making them essential partners in long-term success.

What makes Andhra Pradesh’s APCNF model effective?

The APCNF model emphasizes community ownership, digital integration, and multi-stakeholder financing, resulting in improved incomes, soil health, and farmer participation.

What are the common pitfalls in organic PPPs?

Frequent pitfalls include lack of coordination, poor data integration, political disruptions, and weak grievance mechanisms that reduce farmer trust and impact delivery.

How are PPPs financed in organic farming?

Funding comes from a mix of government subsidies, CSR investments, donor grants, green finance, and private sector contributions like forward contracts and tech support.

What is blended finance in agriculture?

Blended finance combines public, private, and philanthropic funds to reduce financial risk and attract larger investments into sustainable farming practices like organics.

Can organic farming generate carbon credits through PPPs?

Yes, practices like composting and reduced emissions can be certified under carbon markets, allowing farmers to earn additional income through verified carbon offsets.

What technologies are used in digital PPPs for organic farming?

Technologies include satellite imagery, IoT sensors, mobile advisory services, blockchain for traceability, and farm-level monitoring tools like CropIn and Agrivi.

How does digital infrastructure help smallholder farmers?

Digital tools offer timely advice, improve yield forecasts, simplify certification, and enable direct market access, empowering farmers with information and autonomy.

What are Farmer Field Schools (FFSs)?

FFSs are community-based training models that teach organic methods through peer-led demonstrations, improving learning, trust, and farmer-to-farmer dissemination.

Why is farmer trust crucial in PPPs?

Without trust, farmers are reluctant to adopt new practices. Trust grows through transparency, regular engagement, shared decision-making, and timely delivery of support.

How can PPPs support women farmers in organic transitions?

By involving women-led SHGs, providing gender-sensitive training, and offering income opportunities, PPPs can empower women and ensure inclusive participation.

What are Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS)?

PGS is a low-cost, locally driven organic certification system supported by government schemes like PKVY, enabling small farmers to certify produce affordably.

What is the role of monitoring in PPPs?

Effective PPPs use Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) frameworks to track outcomes, improve accountability, and ensure alignment with farmer needs and project goals.

How do PPPs align with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

Organic PPPs contribute to SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption), and SDG 13 (Climate Action) by promoting ecological balance and rural prosperity.

What makes a PPP sustainable in the long term?

Long-term success depends on inclusive governance, adaptive learning, risk-sharing, fair contracts, and strong farmer participation, anchored in ethics and transparency.

Call to Action: Public–Private Partnerships in Organic Farming: Models That Work and What to Avoid

To scale organic farming in India, it’s time for stakeholders—governments, businesses, civil society, and citizens—to come together and co-create impactful public–private partnerships. These collaborations must go beyond token efforts and focus on building resilient, inclusive systems that truly serve farmers. The transition to sustainable agriculture cannot happen in isolation.

Governments must invest not only in policy but in execution, ensuring grassroots participation and responsive governance. Private sector players should see farmers not just as suppliers but as long-term partners deserving of fair prices, training, and tools. This shift in mindset is essential for developing ethical and functional models.

NGOs and academic institutions can drive behavioral change, capacity building, and innovation that are sensitive to local needs. Their experience in working with rural communities makes them valuable mediators in trust-building and accountability. Their insights should be integrated into every stage of the PPP framework.

Finally, consumers and citizens must demand organic and fair food systems, supporting initiatives that prioritize soil health, farmer dignity, and environmental care. By choosing wisely and voicing support for ethical agriculture, each of us can become a part of the larger ecosystem that sustains life and livelihoods

~Authored by Barsha