A Country Drowning in Sewage — The Wake-Up Call

In the mosaic of India’s rapid urban growth, a startling reality often lurks beneath the surface—quite literally. Each day, our cities generate a staggering 72,368 million litres of sewage. Yet, despite this deluge, only about 28% of that wastewater is actually treated—leaving the remaining three-quarters to seep into our rivers, lakes, and aquifers unchecked.

This is not a glitch; it’s a systemic catastrophe. Imagine a bank account into which you deposit ₹100,000 daily—but only receive ₹28,000 in returns. Every day, ₹72,000 vanishes into thin air. That’s today’s scenario for India’s wastewater management: enormous input but minimal recovery, and the rest polluting precious waterbodies.

One of the country’s most tragic illustrations of this disaster lies in the Mithi River in Mumbai. Once named for its “sweet” flow, it now resembles an open sewer flowing through the heart of the metropolis, choked with plastic, industrial grease, and raw sewage. It’s a stark, living symbol of what unchecked domestic wastewater can do to an urban waterway.

Today, with rivers coursing through concrete jungles and pumping out misery rather than life, the urgency is unmistakable. We are not just talking about cleaning water; we’re talking about restoring the very lifeblood of our cities, protecting public health, and preserving ecosystems that have been pushed to the brink.

The Scale of the Problem — How Much Domestic Wastewater and Where It Flows

Every morning, as India’s cities awaken, they generate an astonishing 72,368 million litres of sewage each day—enough to fill more than 30,000 Olympic-size swimming pools. Yet shockingly, only about 28% of that wastewater receives treatment, leaving the remaining 72% to seep unchecked into our rivers, lakes, and groundwater.

To put this in perspective, imagine a fast-moving train carrying 100 carriages, but only 28 of them have safety brakes. One small derailment could threaten the entire system. That’s the precarious situation of India’s water infrastructure: the majority of the sewage—raw, untreated, and hazardous—is allowed to flow freely, posing grave risks to both human health and aquatic ecosystems.

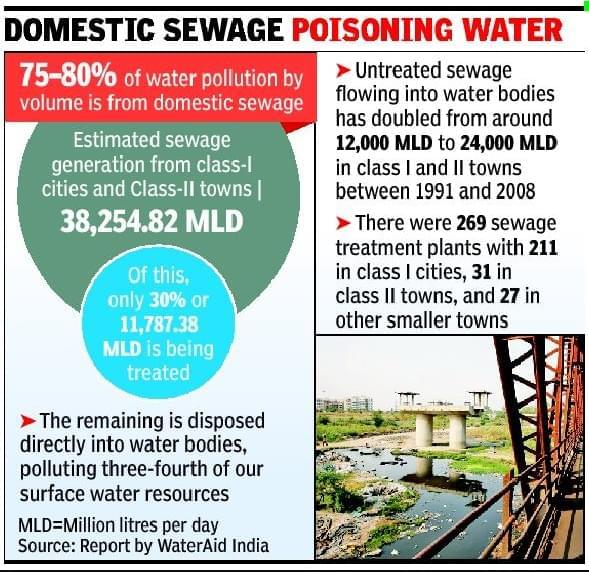

Case in point: class-I and class-II cities, which together account for most of the urban population, produce approximately 38,254 MLD of wastewater, but only about 30% actually undergoes treatment (CEEW). The rest ends up fouling the very rivers and lakes we depend on.

This sewage crisis is not just theoretical—it is visible in our waterways. Take Chennai’s Cooum River, which has been described as a stinking cesspool with virtually zero dissolved oxygen and high levels of faecal coliforms and heavy metals. Nearly 30% of the city’s untreated sewage daily pollutes the Cooum, while the rest is diverted into the Buckingham Canal and the Adyar River.

Another alarming example is Lucknow, where internal reports show that 130 MLD of untreated sewage—out of 730 MLD generated daily—is discharged directly into the Gomti River. That’s nearly a fifth of the city’s sewage bypassing treatment altogether.

And in Maharashtra, the challenges remain stark. While over 9,190 MLD of sewage is generated by more than 400 local bodies, half of it—over 4,500 MLD—is dumped untreated into rivers, making the state responsible for 55 of India’s 351 polluted river stretches.

Such numbers are more than water statistics—they translate into real risks. Rivers with elevated BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) and COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand) levels struggle to support aquatic life, while communities relying on these water sources face threats of waterborne diseases like diarrhoea, cholera, and typhoid. The effects ripple through agriculture, livelihoods, and even cultural practices tied to water.

Sources and Pathways of Domestic Wastewater Pollution

In India, domestic wastewater doesn’t always travel through neatly engineered pipes to distant treatment plants. Rather, it takes a more erratic and often harmful journey—one defined by infrastructure gaps, informal practices, and sheer desperation.

At the heart of the problem lies a fundamental truth: while approximately 60% of Indian households rely on on-site sanitation systems such as septic tanks or leach pits, most of these systems are poorly designed, inadequately maintained, or completely unregulated. A septic tank might seem like a self-sufficient solution, but in cramped urban neighborhoods, there’s rarely room for the accompanying soak pits that are meant to safely percolate treated effluent into the ground. Instead, overflow often ends up in open drains or storm channels—and ultimately in rivers.

This mismanagement is not merely technical—it’s medical. When sewage bypasses even basic treatment, the pathogen-laden effluent travels through our streets before emptying directly into water bodies, fuelling outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, and other waterborne illnesses—a tragic flow from toilet to tide.

Compounding the problem is the endemic failure in faecal sludge management. Though India produces an estimated 120,000 tonnes of fecal sludge daily, nearly two-thirds of it isn’t routed through formal systems—it’s dumped illegally into open land or water bodies. This creates a stealthy but severe form of pollution as sludge seeps into canals, groundwater, or merges with monsoon runoff. It’s a practice as reckless as emptying a septic tank—and as devastating to public health.

Even when authorities attempt to intervene, they often fall short. Take Bhubaneswar, where residents long decried the dumping of faecal sludge by private vendors into open drains—an act supposed to be regulated under the Odisha Faecal Sludge Management Guidelines, 2016. Yet enforcement has been weak. The result? Sludge-laden wastewater continues to ooze into public drains, creating visible hazards in neighborhoods like Old Town and Mancheswar.

In some places, the response has started to shift toward ingenuity. Mobile Treatment Units (MTUs)—truck-mounted systems equipped with filters, membranes, and activated carbon—have been piloted in Tamil Nadu to treat fecal sludge on-site, thereby preventing its illegal disposal into drains or waterways. These units are not a panacea, but they are an example of how creative technology can intercept pollution before it escapes.

In essence, domestic wastewater in India often flows through undefined, unmanaged pathways—from malfunctioning septic tanks to open drains, through uncollected sludge, and finally into rivers. This convolution of neglect and improvisation is more than a sanitation problem—it’s a watershed of public and ecological risk.

Monitoring and Evidence — How We Measure River Contamination

Beneath the surface of polluted rivers lies a vast network of data collection and scientific surveillance, yet the story of India’s river health is one of both insight and blind spots.

India’s water watchdog, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), in partnership with state boards, monitors 719 rivers across more than 2,100 sites, using its National Water Quality Monitoring Programme (NWMP). Rivers, lakes, canals, drains — even creeks and wetlands — are sampled monthly or quarterly, with key indicators like dissolved oxygen (DO), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and coliform bacteria routinely tested. A deeper dive into micro-pollutants like heavy metals and pesticides occurs biannually, before and after the monsoon season.

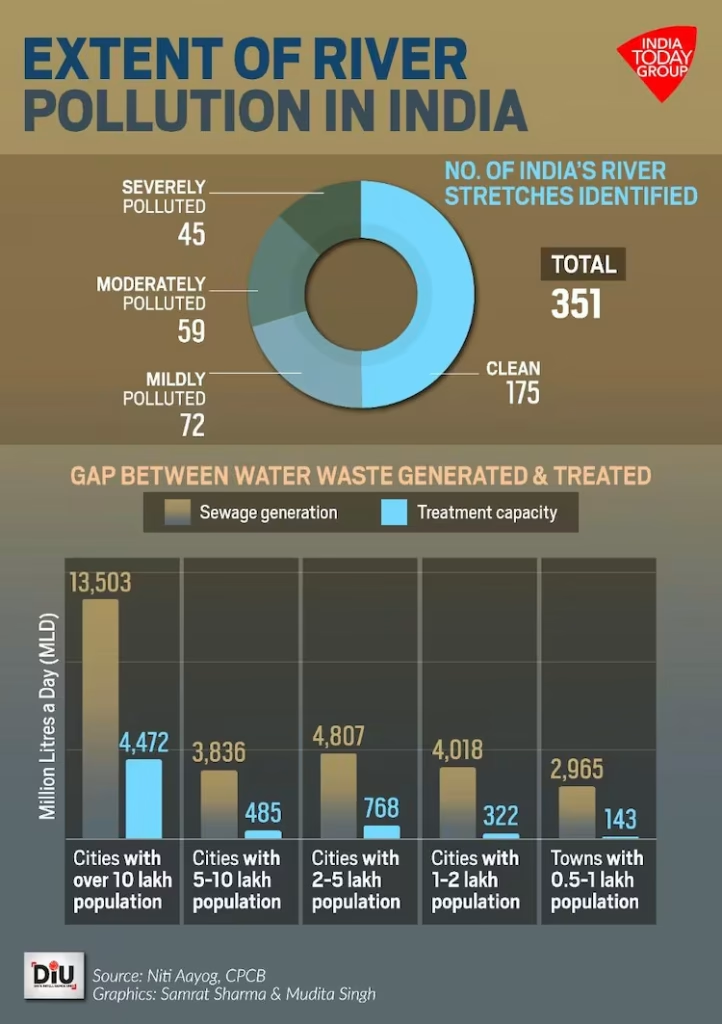

This monitoring reveals an alarming breadth of contamination. As of 2022, 311 out of 603 river stretches—nearly half—are classified as polluted, based on BOD thresholds exceeding 3 mg/L. While this marks a modest improvement from 351 stretches identified in 2018, the pace of recovery remains slow. What’s more, rivers like the Hindon in Noida are effectively “dead” — with zero dissolved oxygen, BOD levels at 50 mg/L, and coliform counts so high they defy safe thresholds—an ecological red alert if ever there were one.

Yet, the system is not without flaws. Monitoring tends to focus on traditional “conventional” parameters — basic chemistry and coliform levels — while neglecting emerging contaminants. BOD, a key indicator of organic pollution, is surprisingly omitted in many assessments, despite being critical to understanding a river’s ability to sustain life. Sampling protocols, too, vary across states, and monitoring frequency doesn’t always match seasonal pollution surges, leaving gaps in temporal or spatial coverage.

Still, there are bright spots. In stretches of the Ganges, for example, continuous monitoring has allowed researchers and authorities to formulate targeted action plans and rejuvenation strategies. Advances in mobile sensor apps—like GangaWatch, which syncs real-time data with historical samples—are making pollution data more accessible to citizens and enabling more grassroots accountability.

All told, monitoring in India is a dual-edged sword. On one side, the data exposes the scale of the crisis and offers a path toward remediation. On the other, critical blind spots and inconsistent protocols can leave the picture incomplete. Strengthening these networks—with better coverage, newer pollutants, and real-time tools—will be essential if we are to transform evidence into effective action.

This infographic highlights the alarming extent of river pollution in India, with 176 stretches classified as polluted and a significant gap between sewage generation and treatment capacity. It underscores the urgent need for effective domestic wastewater management to restore river health.

Treatment Technologies — What Works

India’s sewage crisis is like a wildfire in slow motion—spreading relentlessly through rivers, yet the firefighting response has been uneven and fragmented. Across the country, efforts to combat pollution through sewage treatment technologies—centralized, decentralized, and nature-based—offer glimpses of hope, but the evidence also reveals glaring gaps.

Centralized STPs: Mighty in Theory, Failing in Practice

India’s urban centers have long relied on centralized sewage treatment plants (STPs)—typically using Activated Sludge Process (ASP) or Sequential Batch Reactor (SBR) systems. These mega-structures promise robust pollutant removal, but real-world performance often falls short. A CPCB survey of 152 STPs found that only about 15 out of 19 ASP-based plants met discharge standards—a sobering compliance rate for such high-capacity facilities.

Moreover, even where technology exists, disinfection remains a key vulnerability. In Delhi, fewer than half of operational STPs—just 20 out of 37—have adequate disinfection systems, and only a select few meet the strict norms for preventing microbial contamination. That means rivers like the Yamuna continue receiving water that’s ‘treated’ in name only.

Running these giants also drains energy and finances, and in space-starved cities like Kochi, apartment complexes struggle to install STPs due to a lack of room—depressingly, just 10% of installed capacity is actually used today.

Decentralized Systems (DEWATS / DWTPs): Small Modules, Big Potential

When it comes to adaptability, the decentralized approach often outshines centralized systems, especially in dense or peri-urban contexts. In Northern India, a study evaluating 16 decentralized wastewater treatment plants found them to be relatively affordable, energy-efficient, and operationally versatile—critical traits for resource-limited settings.

Similarly, eight DEWATS plants in Maharashtra consistently produced effluent that met regulatory standards—even if some performed modestly compared to literature benchmarks. These systems often rely on gravity, biofilm reactors, and sedimentation—keeping energy use and complexity low. In effect, they’re pragmatic workhorses rather than showy monuments.

Nature-Based Solutions: Constructed Wetlands & Green Filters

Nature often gives us what we need—if we let it. Constructed wetlands, which mimic natural marshes, offer eco-friendly, low-cost, and low-maintenance wastewater treatment. Their secret lies in plants, microbes, and substrates working together to strip pollutants—even emerging ones like pharmaceuticals—from the water.

Design details matter. Research shows that polyculture systems operating at moderate temperatures (~23–29 °C), with aeration and advanced substrates, significantly enhance nutrient removal—outperforming simplistic, monoculture setups. In areas such as the Ganga basin, horizontal sub-surface flow wetlands are being piloted to safely discharge treated sewage into rivers—bridging tradition and innovation.

Even ordinary invasive plants like water hyacinth lend a green hand: their roots can absorb up to 80% of nitrogen and a substantial share of heavy metals and organic pollutants, making them surprisingly potent, low-cost filters.

This infographic reveals that 75–80% of India’s water pollution comes from domestic sewage, with only 30% treated and the rest contaminating rivers and water bodies. It highlights the urgent need to expand sewage treatment infrastructure to protect freshwater resources.

A Glimpse of Innovation: Gurgaon’s Integrated Model

In a compelling fusion of centralized treatment and clean energy, the Gurugram Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) has revived plans to expand its Dhanwapur STP with Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR) technology and an integrated biogas (CBG) unit. Once complete (by December 2027), this ₹166-cr project will treat up to 318 MLD, reuse water for horticulture, and convert sludge into 5,000 cubic metres of renewable biogas daily—setting a transformative precedent in waste-to-energy urban infrastructure.

Why These Insights Matter

While centralized STPs offer scale, their operational weaknesses—energy intensity, disinfection lapses, and underutilization—dampen their impact. Decentralized systems, in contrast, shine through flexibility and maintainability, even though they serve smaller footprints. And nature-based solutions bring resilience, cost-efficiency, and ecological co-benefits. The bold, emerging hybrid—and circular—models like Gurgaon’s show that when we blend technology with sustainability, we not only combat pollution, but reimagine sewage as a resource.

Community Engagement and Behavioural Change

A river cannot heal itself without the people who live alongside it. In fact, history shows that community participation is often the turning point in any successful environmental restoration effort. From the Yamuna clean-up drives in Delhi to the citizen-led lake rejuvenation in Bengaluru’s Kaikondrahalli Lake, examples abound where the involvement of residents, schools, businesses, and local administrations transformed polluted waters into thriving ecosystems.

Behavioural change, however, is not just about raising awareness; it is about shifting deep-rooted habits that contribute to plastic pollution in the first place. When communities understand the direct link between their daily consumption choices and the health of nearby rivers, the impact is profound. Studies from the UNEP indicate that even a small shift in consumer behaviour — such as switching from single-use plastics to reusable alternatives — can reduce riverine plastic inflow by over 40% within a few years.

For example, in Kerala’s Haritha Karma Sena initiative, women-led neighbourhood groups collect and segregate waste at the household level, ensuring plastics are recycled before they ever reach waterways. The result is not just cleaner rivers but also job creation and community pride. Similar approaches have been championed by Earth5R, where citizen science programs train local volunteers to monitor water quality, conduct clean-up drives, and run awareness campaigns in schools and markets, making environmental stewardship a shared responsibility rather than an abstract concept.

The psychology of behaviour change also plays a role. Researchers point out that visible transformations — like converting a garbage-strewn riverbank into a green community park — create a “positive feedback loop”. Residents who see tangible results are more motivated to maintain the effort. It becomes a story of ownership, where the river is no longer “someone else’s problem” but a shared heritage that needs protection.

In this sense, community engagement acts as the bridge between policy and practice, ensuring that well-crafted waste management strategies do not remain paper promises but become living, breathing movements on the ground. Without this connection, even the most advanced waste management infrastructure risks failing — but with it, rivers have a fighting chance at staying plastic-free for generations to come.

Community-Led & Circular Economy Solutions (Earth5R case studies)

When Delhi’s Yamuna or Mumbai’s Mithi River choked under the weight of domestic wastewater and plastic, the clean-up that many hoped would come from towering institutions came instead from ordinary people—with extraordinary purpose.

Earth5R, a UNESCO-recognized environmental platform, has turned this grassroots momentum into a science-led blueprint for waterbody restoration across India and beyond. Their model harmonizes civic energy with sustainable design, proving that polluted waters can become circular-value resources, not dumping grounds.

Take the Mithi River in Mumbai, for instance—a once-vibrant urban stream that had degenerated into what local officials called a “sewage line,” carrying 93% domestic waste and toxic runoff from surrounding settlements. Earth5R’s Mithi River Project is a circular economy-driven cleanup that isn’t just about trash removal—it’s about transformation. They mobilized communities, businesses, and volunteers to separate, upcycle, and resell waste using their 5R framework: Respect, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Restore.

At the heart of their operation is a solar-powered plastic recovery unit—a clean-energy marvel that scoops up 7–10 tonnes of river plastic every day, washing, shredding, and preparing it for recycling or pyrolysis, with the byproduct oil used in industry. Since October 2020, this initiative has trained 10,000 families and 500 businesses in circular practices. In the process, over 11,100 tonnes of waste were removed and repurposed—a tangible, measurable impact.

But their work doesn’t stop at rivers. Earth5R’s Community-Led Lake Restoration Framework revives toxic urban lakes through scientific cleanup strategies—dredging sludge, aerating oxygen-starved water, and even deploying microbes to restore ecological balance. Crucially, every stroke of the paddle and sweep of the net involves local citizens and students testing pH, dissolved oxygen, and other indicators with mobile apps and drones, merging citizen science with environmental recovery.

Elsewhere in Mumbai’s Ghatkopar neighborhood, Earth5R’s livelihood program introduced a circular-economy model for 35–45 families—most living in informal settlements—teaching waste segregation, composting, and upcycling everyday items into marketable crafts. The result? Over ₹22 lakh in community income generated annually, alongside healthier neighborhoods and greener practices.

These Earth5R models are not altruism—they are actionable proof that clean water, community wellbeing, and sustainable livelihoods can rise together. Whether reviving a river or reforesting a lake, their scaled, grassroots approach shows that meaningful science-based outcomes are most resilient when communities lead.

Earth5R’s Model of Citizen-Led Action for Plastic-Free Rivers

When it comes to creating plastic-free rivers, large-scale government policies and corporate commitments often make headlines. Yet, on the ground, it is the citizen-led movements that frequently deliver the most tangible change. Earth5R, a globally recognized sustainability organization, has pioneered a community-first, circular economy model that transforms waste management from a bureaucratic challenge into a collective civic mission. Through initiatives like the BlueCities Project, Earth5R has demonstrated that urban and rural communities, when empowered, can actively reduce plastic leakage into rivers.

This approach starts with hyperlocal mapping of waste flows, identifying not just where waste ends up but how it travels through communities before reaching rivers. For instance, in cities like Mumbai, Delhi, and Chennai, Earth5R volunteers have conducted extensive waste audits in river-adjacent settlements, revealing that more than 60% of the litter entering waterways is generated within a two-kilometre radius of the banks. This kind of granular data, combined with door-to-door awareness campaigns, helps pinpoint the behavioural and infrastructural gaps that need urgent attention.

What sets the Earth5R model apart is its integration of livelihoods with environmental action. In many interventions, waste pickers—often marginalized and working in unsafe conditions—are formalized into the waste economy through training, protective gear, and access to direct recyclers. This turns an informal, precarious job into a sustainable livelihood while simultaneously diverting tonnes of plastic from rivers. The model ensures that waste is not just collected, but reintroduced into the economy as raw material for manufacturing, supporting the principles of a circular economy.

In Pune, for example, Earth5R’s partnership with local self-help groups and municipal bodies has created plastic banks—drop-off points where residents can deposit segregated waste in exchange for small financial incentives or community benefits like clean water stations. Similar models have been replicated along the Yamuna River in Delhi, where volunteers combine river clean-up drives with public workshops on upcycling plastics into useful products like bags, tiles, and benches.

The impact of such efforts is more than just ecological. They foster a sense of ownership among citizens—the understanding that river health is not a distant policy issue, but a shared community responsibility. This citizen-led stewardship has been shown to create longer-lasting behavioural change than top-down campaigns. It’s the difference between temporary clean-ups and sustained river protection.

Moreover, Earth5R’s success lies in bridging global knowledge with local action. While their model draws inspiration from international best practices in waste management and circular economies, its implementation is deeply rooted in local socio-economic realities. This adaptability has allowed their river projects to scale from urban megacities to smaller towns without losing efficiency.

By championing citizen-led river protection, Earth5R shows that environmental restoration is not merely an act of cleaning—it is a restructuring of community economics, culture, and governance. In the journey towards plastic-free rivers, their model stands as living proof that the most effective change agents are often those who live closest to the water.

The Road to Plastic-Free Rivers

Achieving plastic-free rivers is no longer a utopian ideal—it is an urgent necessity grounded in science, economics, and human survival. The global river systems, from the Ganga in India to the Yangtze in China, are not just water bodies but lifelines for billions. Yet, they are increasingly choked by plastic debris and microplastics, and industrial pollutants, threatening ecosystems, livelihoods, and food chains. The scale of the crisis demands a paradigm shift from reactive clean-up campaigns to a preventive, circular economy-based model that targets the problem at its source.

Experts stress that prevention is not only cheaper but also more sustainable than post-pollution remediation. For instance, a 2022 study in Science Advances showed that stopping plastic leakage at manufacturing and urban waste management levels could reduce riverine plastic pollution by up to 80% in just two decades. This is where integrated strategies—combining policy reform, corporate accountability, community engagement, and technological innovation—become indispensable.

Countries like the Netherlands have demonstrated that targeted interventions, such as the “Plastic Pact” and Deposit Return Schemes (DRS), can dramatically reduce plastic leakage into waterways while fostering a culture of reuse and recycling.

Equally critical is grassroots mobilisation, which organisations like Earth5R have championed through their BlueCities model—a system that merges urban planning, waste segregation, riverbank restoration, and circular business opportunities for local communities. When citizens, corporations, and policymakers work in synergy, river ecosystems transform from polluted drains into vibrant habitats once more. The clean-up of the Seine River in Paris which saw water quality improve enough for certain aquatic species to return, is a testament to what coordinated action can achieve.

However, the path ahead requires persistent political will and economic investment. This is not merely an environmental concern but a socio-economic imperative. Polluted rivers reduce agricultural productivity, increase public health costs, and erode tourism potential—costs far exceeding the price of preventive measures. As global supply chains become more circular, the integration of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), eco-design, and waste-to-resource innovation will decide whether our rivers remain arteries of life or become lifeless channels of waste.

In the words of sustainability advocates, “Clean rivers are not an environmental luxury—they are a basic human right.” The journey to plastic-free rivers is arduous, but with systemic change, innovative solutions, and unwavering public participation, the goal is within reach. The next decade will be decisive—either we close the tap on plastic pollution now, or we allow future generations to inherit a watery graveyard of our negligence. The choice, as always, is ours.

FAQs On Sewage to Solutions: Tackling Domestic Wastewater Pollution in Indian Rivers

What is domestic wastewater pollution and why is it a major issue in Indian rivers?

Domestic wastewater pollution refers to contamination caused by untreated sewage and household waste entering rivers. In India, over 70% of sewage is discharged without treatment, severely impacting river ecosystems and public health.

How much sewage is generated daily in India?

India produces around 72,368 million litres of sewage every day, but the country’s installed treatment capacity is less than half of this amount, leading to large-scale pollution of rivers.

Which are the most polluted rivers in India due to domestic wastewater?

Rivers like the Yamuna, Ganga, Sabarmati, and Mithi face extreme pollution levels, with high biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and faecal coliform counts far exceeding safe limits.

What are the health impacts of domestic wastewater pollution?

Contaminated river water spreads diseases like cholera, typhoid, hepatitis, and dysentery. Prolonged exposure can lead to chronic illnesses and stunted growth in children.

How does untreated sewage affect aquatic life?

Untreated sewage reduces oxygen levels in water, killing fish and other aquatic species. Excess nutrients trigger algal blooms, creating dead zones where life cannot survive.

What role does climate change play in worsening sewage pollution?

Increased rainfall variability and extreme weather events cause sewage systems to overflow, while rising temperatures accelerate microbial activity, worsening water quality.

What is the role of the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG)?

The NMCG implements projects to build sewage treatment plants, intercept drains, and promote community awareness to restore the Ganga and its tributaries.

How is Earth5R addressing wastewater pollution in rivers?

Earth5R works with communities to implement decentralised sewage treatment, riverbank clean-ups, wetland restoration, and citizen education for long-term water health.

Are decentralised sewage treatment systems effective in Indian cities?

Yes. They treat wastewater locally before release, reduce pipeline load, and can be integrated into housing complexes, schools, and industrial areas.

How can households help reduce sewage pollution?

Households can adopt eco-friendly cleaning products, maintain septic tanks, reuse greywater for gardening, and avoid dumping waste into drains.

What is the connection between wastewater and microplastic pollution?

Sewage often carries microplastics from synthetic fabrics, cleaning agents, and personal care products, which accumulate in rivers and enter the food chain.

How does untreated sewage affect agriculture?

Polluted river water used for irrigation contaminates crops with harmful pathogens and heavy metals, posing risks to both farmers and consumers.

What are some nature-based solutions for wastewater treatment?

Constructed wetlands, reed beds, and floating treatment wetlands filter and break down pollutants naturally while supporting biodiversity.

Is wastewater treatment economically viable for India?

Studies show that every ₹1 spent on wastewater treatment yields benefits worth at least ₹4 through improved health, reduced waterborne diseases, and higher productivity.

What laws regulate sewage disposal in India?

The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, and rules under the Environment Protection Act, 1986, mandate treatment of sewage before discharge.

What is faecal coliform and why is it important in water testing?

Faecal coliform bacteria indicate contamination from human or animal waste. High levels signal that the water is unsafe for drinking, bathing, or irrigation.

Can treated wastewater be reused safely?

Yes. Treated wastewater can be reused for landscaping, cooling in industries, flushing toilets, and even aquifer recharge if it meets safety standards.

What is the role of citizens in tackling river sewage pollution?

Citizens can participate in local river clean-ups, monitor pollution levels, conserve water, and hold authorities accountable for sewage treatment.

How does sewage pollution link to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

It directly impacts SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 14 (Life Below Water), and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), making it a global priority.

What is the future outlook if sewage pollution in rivers is not addressed?

If left unchecked, Indian rivers could reach irreversible ecological collapse, leading to loss of biodiversity, unsafe drinking water, and severe public health crises.

Turning the Tide: Our Last Chance for Plastic-Free Rivers

The fight for plastic-free rivers starts in our homes, workplaces, and communities. Every plastic item we refuse, every policy we push for, and every innovation we support adds to a tide of change. Governments must enforce producer responsibility, corporations must design for reuse, and citizens must consume consciously. The time for half-measures is over—act now, support community clean-ups, demand circular waste systems, and back groups like Earth5R. The rivers are waiting—how long will we make them wait?

-Authored By Pragna Chakraborty