Why UN and OECD Roadmaps Matter for Business

UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications is more than a long, unwieldy phrase rather it is a strategic lens through which today’s executives must view every decision. In the next decade, governments will increasingly treat their climate pledges as binding commitments, and businesses must choose whether to adapt or be left behind. These roadmaps offer direction, pressure, and opportunities and understanding them is no longer optional.

In the corridors of power from Geneva to New York, the UN’s climate framework dictates diplomatic direction, while the OECD’s policy architecture translates that direction into economic levers. Together they shape the evolving playing field for industries, capital markets, and supply chains. For companies, ignoring these roadmaps is akin to dismissing a new legal operating system,one that will govern how assets are valued, how risks are measured, and where investment flows go.

Consider a global manufacturer contemplating where to build its next plant. Beyond cost, workforce, and logistics, it must now evaluate climate alignment. Will the host country raise its carbon price soon? Will stricter emissions limits or mandatory reporting rules apply? Will the infrastructure support renewable energy? These are no longer “maybe someday” concerns; they are embedded in the UN and OECD frameworks that governments worldwide are ratcheting upward.

From a capital allocation perspective, these roadmaps shift the distribution of financial winners. Pension funds and sovereign wealth funds are under pressure to divest from high-carbon assets; banks are beginning to price transition risk into lending rates. The OECD’s approach, in particular, demonstrates that a coherent OECD net zero roadmap is not just metaphorical , it influences how policy, taxation, and public investment reshape entire sectors. Companies that embed corporate climate strategy now can preserve optionality; those that lag will pay premium refinancing costs or see their assets stranded.

On the supply chain front, the trickle-down effects are immediate. Large corporates will demand climate compliance from Tier 1 and Tier 2 suppliers. A food brand might insist its farmers commit to emissions reductions or regenerative practices. A retailer could require disclosure of Scope 3 emissions across its logistics network. Such pressures cascade from the top: a UN-backed national policy pushing carbon pricing or mandatory climate risk reports will force procurement teams to vet climate credentials. In effect, the roadmaps shift the locus of compliance not just vertically, but horizontally.

The shifting paradigm: from compliance to strategic advantage

To appreciate why these roadmaps matter, imagine climate policy as tectonic plates. For decades, climate regulation was a regional tremor ,local carbon taxes, emissions trading zones, cap-and-trade systems. But now, the UN and OECD frameworks are pushing entire continental plates: a global reorientation of industrial norms, financial flows, and legal risk. Companies that align early surf the wave; those that lag may find themselves offshore.

Unlike earlier eras, when firms saw climate policy as a cost of doing business, today’s forward-thinking firms see climate risk and opportunity for business as a source of differentiation. A firm that embraced internal carbon pricing years ago may now report steadier margins as external prices tighten. A corporation that piloted low-carbon materials or circular loops can command premium positioning in decarbonizing markets.

As one climate economist put it, “The cost curve is real, and it’s steepening.” Firms that engage with these roadmaps now act not just defensively, but strategically. They reconfigure R&D, capital expenditure, and partnerships around the new baseline. In that sense, the UN and OECD roadmaps function as a compass: they reveal which direction policy wind is blowing, allowing business to set their sails accordingly.

What the UN and OECD Roadmaps Actually Say

In order to bridge climate ambition with corporate reality, business leaders must understand the substance behind the frameworks. The UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications emerge not as abstract ideals but as structured architecture: the UN sets global ambition and political accountability, and the OECD builds the policy tools and economic grounding to implement it. Below, we explore each roadmap’s essentials and begin to surface how they translate into risk, opportunity, and strategic direction for firms large and small.

UN Climate Guidance: Core Elements and Timelines

The United Nations’ climate guidance is anchored in the Paris Agreement architecture. At its heart lies the concept of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): every signatory nation must spell out its emissions-reduction and adaptation goals and revisit them every five years. In plain terms, there is no static plan,the path must steepen over time. In 2025, many nations will submit their “NDC 3.0” updates, informed by the outcomes of the first global stocktake.see here

This rolling cycle of ambition is designed to force upward ratcheting: each revision is expected to be more aggressive than the last. For the private sector, that means business plans cannot assume flat regulatory regimes; they must anticipate escalation. According to the 2024 NDC Synthesis Report, 153 parties have already submitted new or updated commitments, covering ~95 % of global emissions. UNFCCC

A second pillar of UN guidance is climate finance flows. The UN and related institutions expect that capital both public and private must redirect toward decarbonization and resilience. Developed countries reaffirmed a commitment to mobilize USD 100 billion annually toward climate goals. That promise has repeatedly come under scrutiny, but momentum is building: in 2022, developed nations reportedly exceeded this threshold, reaching nearly USD 116 billion in climate finance.see here

Yet adaptation funding remains under-resourced. The Adaptation Finance Gap Update 2023 underscores that global demand far outstrips supply , many national adaptation plans (NAPs) still lack full financial backing see here. Businesses that can partner on adaptation (e.g. resilient infrastructure, water management) may tap into this gap.

A third central dimension is the balance between mitigation and adaptation. The UN’s guidance does not treat emissions cuts as the only pillar but it elevates adaptive capacity as equally essential. The Global Goal on Adaptation, embedded within the Paris framework, compels that countries (and their corporate sectors) manage climate risks, not just emissions.see here

Timelines matter deeply. Many nations, drawing from UN pathways, now commit to net-zero by 2050, with interim pledges such as 30–50% emissions reduction by 2030. According to the OECD and IPCC aligned projections, global GHG emissions must fall by ~43 % by 2030 from 2019 levels to keep 1.5 °C within reach see here. However, current pledges only deliver ~14 % cuts ,a gap the OECD warns will force steeper policy interventions later.

In sum, the UN climate roadmap is the north star: raising ambition every five years, channeling finance to mitigation and resilience, and imposing dual responsibility for emissions and adaptation. For business leaders, these signals are not hypothetical; they are timelines for alignment or risk misalignment.

OECD’s Net-Zero / Net Zero+ Framework : Policy Levers & Economic Framing

While the UN gives direction, the OECD net zero roadmap is expressed chiefly through its Net Zero+ horizontal project, which describes how economies must reorganize to deliver on the ambition. Net Zero+ is not a stand-alone policy manual but a synthesis across more than 20 OECD committees, offering coherent and resilient policy packages.see here

One of the foundational principles of Net Zero+ is horizontal integration: climate policy cannot be siloed in environment ministries. It must be woven into industrial, trade, fiscal, labor, energy, and innovation policy. The OECD calls for policy coherence,that is, avoiding conflict where, for example, industrial incentives undercut emissions goals.

Carbon pricing remains a central tool in the OECD’s approach. Whether through carbon taxes or emissions trading systems, putting a meaningful price on CO₂ creates market signals. The OECD’s “Net Zero by 2050” report maps out how a combination of carbon pricing and structural policies can steer energy systems toward renewables.see here Firms will find that internal carbon pricing becomes less voluntary and more normative ; a precursor to regulation.

On infrastructure, Net Zero+ emphasizes public investment in clean energy, electrification, grid resilience, and low-carbon transport. These investments, it argues, can crowd in private capital and accelerate deployment. The OECD also encourages green procurement practices to signal demand for low-carbon goods.

A less visible but potent lever is Mission-Oriented Innovation Policies (MOIPs). The OECD has documented over 100 national “net-zero missions” purpose”-driven R&D programs targeting decarbonization in sectors like hydrogen, sustainable materials, and carbon dioxide removal.see here For businesses, MOIPs present early market shaping opportunities and public-private partnerships.

Crucially, Net Zero+ embeds resilience and equity into its policy sequencing. The framework warns against abrupt transitions that could destabilize economies or intensify inequality. Instead, it recommends phased policies, support for displaced workers, and mechanisms to smooth adaptation. In effect, the OECD net zero roadmap is designed not just to reduce emissions but to do so in socially sustainable and politically stable ways.

Furthermore, the OECD links these policies to benchmarking and tracking via IPAC (International Programme for Action on Climate). Through IPAC, climate indicators ranging from carbon intensity to adaptation investment can be compared across countries, sectors, and time. This transparency pushes governments and private actors toward accountability.

To illustrate, imagine a country deploys a national hydrogen mission as part of Net Zero+, subsidies for electrolysis, combined with carbon pricing on natural gas. It also invests in transmission infrastructure, mandates greener procurement, and supports workforce retraining. That integrated package embodies the OECD net zero roadmap in action.

From a business perspective, every element of Net Zero+ carries implications: carbon pricing reshapes cost structures, public infrastructure dictates location arbitrage, innovation roadmaps shape technology risk, and sequencing strategies reduce regulatory shocks. In the next section, we will translate these frameworks into direct business implications, risk metrics, and opportunity zones,but the foundation is set: the UN determines the ambition; the OECD provides the scaffolding.

Scientific evidence and economic modelling backing the roadmaps

To make sense of UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications, one must go beyond political statements and inspect the models, data, and macro forecasts that underpin them. In this section, we explore first how climate scenarios frame possible futures, then how macroeconomic modeling evaluates the trade-offs of action or inaction. These insights ground roadmap commitments in empirical reality and point to how firms can interpret them in strategic terms.

Climate modelling and scenarios (IEA / OECD / UNDP / peer-reviewed studies)

When climate scientists and economists build pathways toward 1.5 °C or 2 °C, they do so with integrated assessment models (IAMs), energy-economy models, and sectoral decarbonization trajectories. These are not predictions, but illustrative scenarios that show what would be required to stay on track. Such scenarios are foundational to both UN and OECD roadmaps as they define what “feasible ambition” looks like.

The IEA’s updated Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach offers one of the most authoritative views. It lays out a Net Zero Emissions (NZE) scenario for the energy sector, consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 °C, albeit with limited overshoot. In this scenario, global emissions from energy must decline sharply; clean technologies must be scaled rapidly; and energy systems become far more efficient.see here

Under the IEA pathway, by 2030 the world economy is projected to be about 40 % larger than today, yet consume 7 % less energy, thanks to efficiency gains averaging 4% annually. That means decoupling growth from energy use which is a central tenet of low-carbon transitions. The path is narrow: any delay or deviation risks locking in emissions incompatible with 1.5 °C.

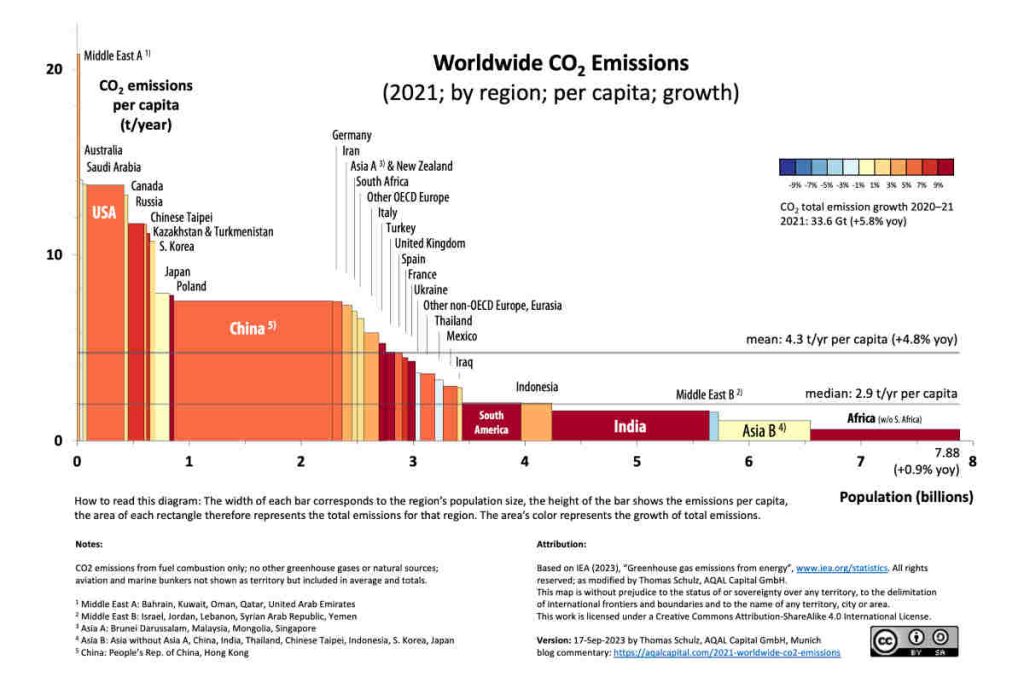

Sectorally, the modelling points to steep reductions in carbon-intensive industries. For example, in the oil and gas sector, emissions must fall by more than 60 % by 2030 from current levels, and operations must approach near-zero intensity in subsequent decades . In other sectors such as power, transport, heavy industry ,the models demand radical shifts: electrification, fuels substitution, carbon capture, circular economy practices, and aggressive efficiency. These models also underscore limited roles for new fossil fuel development in many pathways, no new long-lead fossil fuel projects are viable under a 1.5 °C path.see here

The models use scenario lexicons like STEPS (Stated Policies), APS (Announced Pledges), and NZE (Net Zero Emissions) to illustrate gaps between current policies and what is required. STEPS often leads to ~2.4 °C trajectories, and APS to ~1.7–1.8 °C, whereas NZE is the normative path to 1.5°C. Because current NDCs fall short, the “ambition gap” is central: many published policies lag behind what models deem necessary to stay within safe temperature limits

These scenario results carry business implications of climate roadmap logic: if models show that only aggressive transitions avoid dangerous warming, then policy is likely to tighten. Firms must see these scenarios as guardrails for their own corporate climate strategy rather than wishful forecasts.

Macro-economic findings : costs vs benefits for economies and firms

While climate models define physical and technological pathways, macroeconomic modeling asks: What is the cost and the upside of following these pathways? How do emissions cuts, adaptation, and climate risk weigh against economic output, productivity, and investment?

A recent joint OECD-UNDP study makes headlines: it finds that accelerated climate action could raise global GDP by 0.2 % by 2040, compared to business-as-usual. That may seem modest, but when compounded and viewed through avoided climate damages, that upside is nontrivial. The analysis suggests that well-designed climate policies can catalyze efficiency gains, innovation, and productivity not just costs. see here In effect, climate action is not a drag, but a catalyst ;especially when paired with structural reforms.

Beyond 2040, the gains compound. The OECD modeling suggests that stronger NDC scenarios might boost global GDP by up to 3 % by 2050 and as much as 13% by 2100, relative to paths that fail to upgrade ambition. Those projections embed avoided damages, enhanced resilience, and technological dividends.

Closer to the present, the modeling pins near-term gains: under an “Enhanced NDCs” scenario, global GDP is projected to be 0.12 % higher in 2030, 0.20 % higher in 2035, and 0.21 % higher in 2040 versus current policy baselines (even without counting reduced climate damages). These increments may seem small, but for large economies they translate into meaningful absolute gains.

Yet the counterfactual is stark. Other studies warn that failing to address climate change could cost up to 4 % of global GDP by 2050, especially in vulnerable regions, due to increased heat, flooding, productivity disruptions, and ecosystem loss.see here For firms, these losses could manifest as destroyed assets, supply chain shocks, increased insurance premiums, and depressed demand.

In sum, the macro evidence tilts toward “act early.” The business implications of the climate roadmap point to a world where the penalty for delay exceeds the cost of transition. Particularly for capital-intensive sectors, early investment in decarbonization can yield first-mover advantages, avoid stranded assets, and capture upside from emerging green markets.

Direct business implications : risks, costs, and opportunities

When the global architecture shifts as encapsulated in the UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications , it is not abstract for firms. The consequences cascade into four main arenas: regulatory risk, physical risk, transition opportunity, and capital & financing dynamics. To translate policy into boardroom strategy, executives must understand how these high-level commitments intersect with operational realities.

Regulatory and policy risks

If governments adhere to their climate roadmaps, corporations are likely to face a wave of stricter regulatory mandates. Emissions limits will become tighter, fossil-fuel subsidies will gradually be phased down, and mandatory disclosures modeled after TCFD or ESRS (European Sustainability Reporting Standards) are becoming the norm rather than the exception.

Across jurisdictions, more companies are being required to disclose climate-related risks in their financial filings. In the United States, the SEC adopted rules in March 2024 that require disclosure of material Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, as well as financial impacts of severe weather eventssee here. In Europe, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) integrates double materiality and broadens disclosure requirements — many firms outside the EU must comply if they operate there.see here

The supply chain dimension compounds the pressure: a lead company may insist that every supplier disclose emissions or commit to emissions reduction targets, deferring responsibility down the chain. This trickle-down compliance means regulatory risk is not confined to regulated entities alone asit touches Tier 2, Tier 3 suppliers as well.

For many firms, the business implications of climate roadmap frameworks will manifest as compliance costs, legal exposure, and increased administrative burden. The cost of preparing disclosures, securing third-party verification, and integrating new reporting systems can be substantial, especially for companies in fragmented or global chains.

To stay ahead, companies should treat emerging regulation as intelligence rather than hindrance: tracking draft rules in home and host markets, engaging proactively in public consultations, and modeling how future emissions limits might affect product lines, geography, and operations.

Physical climate risks across asset classes

Even if a company navigates regulatory risk successfully, it cannot ignore physical climate risk. This risk manifests across asset classes: factories can flood, logistics routes may become impassable under extreme weather, commodity yields can drop, and insurance premiums can skyrocket.

In operations, heat stress can force production slowdowns, and water scarcity can jeopardize cooling or processing systems. Real estate is vulnerable: coastal warehouses, air-conditioning intensive buildings, and supply hubs may lose value. Logistics routes that cross flood-prone or storm-affected zones may face frequent disruption.

Commodity price volatility is another vector of risk. For instance, droughts in agricultural belts could spike feedstock prices, squeezing margins in food, beverage, or textile firms. Insurers already price climate premiums accordingly: a recent empirical study found that firms with high environmental risk profiles face higher debt costs and cost of capital.see here

Physical risk also interacts with debt: in a study published in 2025, firms exposed to high physical climate risk show a tendency to prefer short-term and less-interest-bearing debt to reduce refinancing exposure.see here

For firms, the implication is clear: risk mapping matters. Conduct scenario stress analysis,model floods, drought, heat extremes and translate them into financial exposure on operations, balance sheet assets, and insurance costs.

Transition opportunities and upside

If risk is one side of the coin, opportunity is the other. Aligning early with climate roadmaps opens access to new markets , be they clean energy, circular economy models, low-carbon materials, or resilience services. Firms that embrace these trends may capture first-mover advantages in nascent sectors.

Efficiency and productivity gains also accumulate. Reducing energy waste, optimizing logistics, deploying digital monitoring, and retrofitting assets all improve cost structure. A well-known example: when a global industrial client adopted AI-based energy management, it cut electricity consumption by 10–15% a freeing margin and strengthening resilience under energy price shocks.

Investor sentiment now favors net-zero-aligned firms. ESG funds, green bonds, and climate-focused capital allocations prioritize low-carbon profiles. Firms that embed corporate climate strategy early may attract cheaper capital or sustained investor support.

New business models can emerge: modular renewables, energy-as-a-service, product-as-a-service (circular leasing), and carbon-as-a-service offerings are nascent but growing. The business implications of a climate roadmap therefore include being proactive about business model innovation and not waiting until regulation forces a pivot.

Capital & financing implications

Finally, the sketches drawn by climate roadmaps extend into capital markets. Companies with weak climate credentials often face higher capital costs. A systematic literature review confirms that firms with negative environmental profiles tend to have higher weighted average costs of capital (WACC) and higher interest rates.

Moreover, transition risk is increasingly priced into equity: a working paper shows that firms with higher exposure to climate transition risk—especially when the risk is salient to markets face higher cost of equity.see here Meanwhile, physical and policy risks appear to suppress capital allocations in affected firms.

Banks and lenders are also tightening scrutiny. Loan conditionality , requiring emissions targets, penalty clauses for overshoots, or climate-aligned capital expenditure is becoming common. Green loans and sustainability-linked loans come with interest-rate discounts tied to performance targets. A 2025 article on green finance finds that such instruments are reshaping how firms deploy capital.see here

Finally, investor stewardship expectations are maturing. Institutional investors demand disclosure, scenario alignment, and forward-looking climate commitments. Companies may face divestment or reluctance to invest if they lack credible decarbonization pathways.

Sector-level implications & metrics : where to prioritize action

Even though UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications apply broadly, their real force is felt sector by sector. Some industries face more immediate pressure; others have greater opportunity to reshape value chains. Below we explore four critical sectors , energy & utilities, manufacturing & heavy industry, agriculture and food, and financial services , showing both risks and levers of action. In each, we also propose KPIs that firms should monitor as they realign with roadmap trajectories.

Energy & utilities: decarbonization pathways and stranded asset risk

The energy sector lies at the heart of the climate transition, and its decisions will ripple across all others. Under both UN and OECD frameworks, energy and utilities must move aggressively toward low- or zero-carbon generation, while simultaneously managing stranded-asset risk in legacy fossil infrastructure.

Decarbonisation pathways typically call for phasing out unabated coal, shifting to renewables (wind, solar, hydro), deploying storage, demand-side flexibility, and clean dispatchable backup. In many scenarios, by 2030 the electricity sector must reduce emissions intensity dramatically, with near-zero carbon generation by 2050. Firms will see fossil plants become economically unviable long before their technical end of life.

Stranded asset risk is real: assets such as coal-fired power plants, natural gas peaker plants, or transmission lines designed for fossil-based load may become liabilities. A utility that ignores these risks might find itself saddled with write-downs or forced to retrofit at high cost. Conversely, early movers in grid modernization, battery storage, hydrogen integration, and carbon capture could capture growth markets.

Suggested KPIs for energy & utilities include:

KPI 1: CO₂e intensity (g CO₂/MWh or t CO₂ per unit generation); tracks how “clean” generation is evolving.

KPI 2: Scope 1 & 2 emissions coverage; share of emissions under direct control or from purchased energy.

KPI 3: Scope 3 emissions (e.g. fuel supply chain, downstream use) ; useful for integrated utilities.

KPI 4: Carbon price sensitivity metric: estimated impact on cost/revenue per $/ton CO₂ change.

KPI 5: Physical risk exposure metric; percentage of assets in flood zones, heat stress zones, or with water scarcity risk.

For example, a European utility may forecast that a $50/ton carbon price will reduce profitability of gas plants, pushing them into retrofitting or early retirement. Meanwhile, deploying battery and solar capacity may reduce the plant’s carbon intensity metric below industry benchmarks. Strategic firms will monitor carbon price sensitivity and asset-level risk exposure to manage both transition and physical risks.

Manufacturing & heavy industry: process emissions, circularity, and material substitution

Manufacturing and heavy industry (steel, cement, chemicals, metals) are among the hardest-to-abate sectors. Their emissions often come not just from energy use but from process emissions such as intrinsic chemical reactions (e.g. CO₂ released in cement calcination). Under UN and OECD roadmaps, decarbonisation demands both energy switching and process redesign.

The Sectoral Decarbonization Approach (SDA) has been used to allocate sector-specific emissions pathways aligned with 2 °C or 1.5 °C trajectories. Firms that adopt SDA-derived benchmarks commit to CO₂e intensity per unit of output consistent with global budgets. (Science Based Targets Initiative / public documents)

Circularity and material substitution are also critical. For instance, using recycled feedstock or alternative lower-carbon materials can bypass process emissions altogether. For aluminum, electrified smelting or inert anode technologies are emerging. In cement, blending with supplementary cementitious materials and carbon capture are necessary to meet roadmap-aligned pathways.

Suggested KPIs for manufacturing & heavy industry include:

KPI 1: CO₂e intensity (t CO₂ per product unit, e.g. per tonne steel)

KPI 2: Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions coverage (especially upstream material sourcing)

KPI 3: Carbon price sensitivity: estimated increase in cost per ton of output under projected carbon costs

KPI 4: Physical risk exposure metric: share of plants in zones linked to flooding, heat, or input-water dependency

An industrial firm might simulate how raising carbon cost to $75/ton would raise input costs in its chemical units, forcing a shift to greener feedstocks. A diversified steel producer might benchmark its CO₂e intensity against SDA-aligned targets and flag sites in coastal or flood-vulnerable zones for divestment or retrofitting.

Agriculture, food & commodities : supply chain resilience and scope-3 exposure

Agriculture, food processing, and commodity sectors face a dual challenge: direct emissions (on-farm, feedstock, processing) and vast Scope 3 exposure through upstream and downstream supply chains. Because supply chains often cross borders, the UN climate roadmap’s push for decarbonization and the OECD net zero roadmap’s trade & policy coherence both hit this sector hard.

In many food and agribusiness firms, upstream Scope 3 (fertilizer production, land-use change, upstream energy) constitutes the largest share of emissions , sometimes as much as 70 %. (WEF article: Scope 3 emissions key) Addressing that requires deep engagement with farmer practices: regenerative agriculture, soil carbon sequestration, precision farming, and biodiversity safeguards.

Resilience also matters. Climate-induced disruptions (drought, flooding, pest outbreaks) threaten supply continuity. Firms must ensure supply chain resilience, diversify sourcing, and build buffer capacity. The climate roadmaps’ emphasis on adaptation pushes firms to internalize physical risk into procurement decisions.

Suggested KPIs for agriculture, food & commodities include:

KPI 1: CO₂e intensity (kg CO₂e per tonne product or per unit of output)

KPI 2: Scope 1, 2, and upstream Scope 3 coverage share

KPI 3: Carbon price sensitivity: cost increase per kg product if carbon priced at $X/ton

KPI 4: Physical risk exposure metric: fraction of suppliers in high climate vulnerability zones

A global food brand may require its suppliers (farmers) to reduce nitrogen fertilizer use or switch to lower-carbon feedstock. It may simulate what happens if a drought forces crop yield down 20%: how much margin erosion would occur? It might flag suppliers in climate-vulnerable geographies and source alternatives.

Financial services : scenario analysis, stress testing & disclosures

Financial institutions sit at the intersection of carbon finance, risk allocation, and capital flow ,making this sector pivotal to the success of climate roadmaps. The business implications of the climate roadmap for banks, asset managers, insurers, and pension funds are immense: they must integrate climate metrics, manage financed emissions, and quantify risk under multiple scenarios.

Under the OECD net zero roadmap, financial institutions are expected to embed climate into core risk frameworks, align capital allocation with decarbonization goals, and support climate-linked disclosure frameworks such as TCFD, ISSB, or ESRS. They must also withstand scrutiny under scenario analysis and stress tests,imagining a world under 1.5 °C, 2 °C or 3 °C warming and calibrating potential losses accordingly.

Suggested KPIs for financial services include:

KPI 1: Financed emissions (CO₂e) per portfolio, broken down by sector

KPI 2: Coverage share of clients with emissions disclosure / climate targets

KPI 3: Carbon price sensitivity metric: exposure per $/ton CO₂ in lending / investment portfolios

KPI 4: Physical risk exposure metric: share of assets or clients in climate-vulnerable geographies

Financial firms will stress-test loan books, investments, and insurance portfolios for transition and physical shocks. For example, banks might simulate a scenario where carbon pricing jumps to $100/ton or extreme flood events hit key real estate assets. Institutions with high financed emissions, especially in heavy industry or energy ,may need to reserve additional capital or de-risk exposures proactively.

By viewing these sector-level implications through the lens of corporate climate strategy, firms can diagnose which business units are most exposed, where capital should shift, and how to set meaningful KPIs that align with the broader roadmaps.

Case Studies: How Local Action Maps to Global Roadmaps

When we speak of global climate ambitions, the conversation often feels remote dominated by summit declarations and economic models. Yet, the success of the UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications depends on what happens at the local level. In India, Earth5R has turned climate theory into measurable practice, proving that small, data-driven community actions can align perfectly with global sustainability frameworks.

Case Study 1: Earth5R; Rural Sustainability Model (Five-Pillar): Supply-Chain Resilience and Community Partnerships

Earth5R’s Rural Sustainability Model represents one of the clearest demonstrations of how grassroots initiatives can directly support the UN climate roadmap. The model is built on five interconnected pillars ; organic farming, water conservation, waste management, renewable energy, and rural livelihoods. Each pillar contributes to a self-sustaining ecosystem where community well-being and climate resilience advance together.

In the Himalayan villages of Uttarakhand, for example, Earth5R worked alongside women-led self-help groups to reintroduce organic turmeric cultivation, build composting units, and dig rainwater trenches on slopes to restore soil health. These seemingly small actions had measurable outcomes: improved water retention, increased yields, and a 40 percent drop in chemical input costs. In Solapur, Maharashtra, farmers learned to turn crop residue and food waste into compost, cutting fertilizer expenses while enriching soil fertility.

What stands out is how these programs created a ripple effect beyond environmental metrics. They enhanced supply-chain resilience for companies sourcing agricultural materials, stabilized local economies, and generated alternative livelihoods ;especially for women. The Rural Sustainability Model is not merely an environmental program; it is a microeconomic blueprint for corporate sustainability. Businesses can learn from its logic: a resilient supply chain starts with resilient communities, and investments in soil and water stewardship translate directly into long-term operational stability.

Case Study 2: Earth5R : Carbon-Neutral Communities Blueprint: Hyperlocal Pilots and Scaling Lessons

If the rural model focuses on the supply side of sustainability, Earth5R’s Carbon-Neutral Communities Blueprint shifts the spotlight to cities and neighborhoods where consumption, waste, and emissions converge. This initiative aims to prove that even the most densely populated localities can achieve measurable decarbonization when citizens and businesses collaborate.

In Mumbai’s informal settlements, Earth5R facilitated solar lighting installations, community composting, and waste segregation programs that reduced grid electricity dependency and methane emissions from unmanaged waste. Each community’s carbon footprint was tracked in real time through digital dashboards ; a model that converts everyday behavioral changes into quantifiable emissions data. Over time, electricity use dropped, waste generation fell, and air quality improved, offering a practical template for replication in other cities.

What makes this blueprint remarkable is its potential for public-private synergy. Small and medium enterprises can join these community projects by sponsoring renewable infrastructure, recycling drives, or local clean-energy initiatives. Such partnerships not only shrink neighborhood footprints but also unlock reputational and financial dividends through verified carbon credits and social-impact data. In essence, Earth5R’s Carbon-Neutral Communities project offers a tangible example of how urban micro-interventions can reflect the broader goals of the OECD net zero roadmap, connecting local progress to national decarbonization targets.

Case Study 3: Earth5R: Action Grid and River Cleanup: Stakeholder Engagement and Measurable Remediation

Few stories illustrate the bridge between local action and global vision better than Earth5R’s Action Grid, particularly its work on the Mithi River in Mumbai. Once notorious for pollution and flooding, the river became a living laboratory for community-driven restoration. Earth5R mobilized residents, students, and local businesses to remove solid waste, segregate recyclables, and advocate for upstream waste management.

The initiative didn’t stop at cleanup events. Through the Action Grid’s digital monitoring system, every kilogram of waste removed, every improvement in water quality, and every hour of community participation was logged and visualized. Transparency was key as it allowed municipalities and citizens alike to see the results, building trust and accountability.

This project created more than cleaner water; it reshaped perceptions of shared responsibility. Businesses that collaborated with the initiative found an unexpected reward: stronger community relations and reputational gains. In a world where ESG metrics drive investor sentiment, demonstrating measurable remediation aligned perfectly with the business implications of climate roadmap thinking. The Mithi River model shows that environmental rehabilitation, when documented rigorously, becomes both a civic contribution and a brand asset.

OECD and IEA Benchmark : National Roadmaps That Influenced Corporate Policy

The lessons from Earth5R’s work find echoes at the national level, where OECD and IEA roadmaps have redefined how governments and industries interact. A powerful example comes from Europe’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which translates climate ambition into economic law. By placing a carbon price on imported goods, the European Union effectively nudged manufacturers worldwide to adopt lower-emission processes or risk losing access to one of the largest markets on earth. The ripple effect was immediate: steel and cement producers in Asia began investing in green hydrogen, carbon capture, and circular materials to maintain competitiveness.

Similarly, the IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 Roadmap has guided national policy shifts in Japan and South Korea. When both nations committed to net-zero targets, energy conglomerates rapidly diversified toward renewables and hydrogen, anticipating regulatory incentives and investor preference for low-carbon portfolios. This demonstrates the economic leverage of coordinated policy is a hallmark of the OECD net zero roadmap, which emphasizes policy coherence across energy, industry, and finance.

These national examples reinforce a central truth: when governments adopt clear, science-based climate strategies, businesses respond decisively. Corporate boards reallocate capital, investors recalibrate portfolios, and innovators step in to seize emerging markets. The trajectory from OECD analysis to corporate boardroom decision-making underscores why climate policy cannot remain abstract , it shapes real-world profit and loss.

The Convergence of Local Innovation and Global Ambition

Taken together, these case studies show how UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications are not confined to treaties or reports. They live and breathe through local experiments, community pilots, and corporate pivots. Whether it’s a farmer composting organic waste, a city resident installing solar panels, or a manufacturer redesigning production to meet a new emissions threshold, each action adds a measurable pixel to the global picture.

Earth5R’s grassroots innovations and OECD’s global frameworks meet on common ground: both prioritize measurable outcomes, transparency, and shared responsibility. What starts as a compost pit in a village or a river cleanup in a city scales into a template for resilient economies and sustainable growth. For businesses, this is not peripheral activism; it’s a playbook for the future ; a reminder that aligning with climate roadmaps is not just compliance, but competitiveness.

Practical roadmap for businesses : step-by-step alignment checklist

Understanding the UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications is only the beginning. The harder part and the one that truly defines competitive advantage is execution. Businesses must move from awareness to structured, measurable action. This means building governance systems, mobilizing capital, reshaping supply chains, and cultivating transparency over the next decade.

The journey to climate alignment unfolds in phases ; immediate, medium, and long term. Each phase builds on the last, reflecting how climate strategy should evolve from compliance to innovation and ultimately, to leadership.

Immediate (0–12 months): governance, disclosure, and scenario mapping

The first twelve months should focus on laying the foundation. Governance, transparency, and risk mapping are the bedrock of credible climate action.

Companies must begin by embedding climate governance into their top management structures. That means assigning board-level accountability for climate oversight often through a sustainability committee or by linking executive incentives to climate performance. According to the OECD’s Corporate Governance Factbook (2024), firms with dedicated climate oversight at board level tend to adopt more ambitious mitigation targets and disclose progress more reliably. (oecd.org)

Parallel to governance comes disclosure. Frameworks such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) set global standards for climate-related reporting. Firms should assess which elements such as governance, risk management, metrics, and targets that they can disclose immediately and which require data maturity.

Scenario mapping is equally critical. Businesses should stress-test their portfolios under various climate futures: What happens if global temperature rise is limited to 1.5 °C? What if carbon prices double or physical risks materialize faster than expected? Tools like the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) scenarios or IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 pathway, can help firms understand exposure.

At this stage, even simple steps such as internal carbon pricing or conducting a life-cycle assessment (LCA) can yield strategic clarity. Internal carbon pricing , used by more than 2,000 companies globally forces decision-makers to recognize carbon as a real cost when evaluating new projects. LCAs identify hidden emissions in products and processes, revealing where efficiency can be achieved fastest.

For companies operating in communities, adopting Earth5R-style hyperlocal pilots is another practical move. A small solar installation or circular-waste initiative can generate local data, stakeholder trust, and quick-win metrics that strengthen ESG narratives. As Earth5R’s projects have shown, early action at the local level builds momentum that formal reporting alone cannot match.

Medium (1–3 years): capital reallocation, supplier engagement, and pilot projects

Once governance and disclosure systems mature, the next step is operational transformation where budgets, capital, and partnerships begin to align with the roadmap.

This phase often involves reallocating capital expenditure toward low-carbon technologies. Energy-intensive industries can retrofit plants with electrified equipment, renewable power, or carbon-capture systems. For financial institutions, it means aligning lending portfolios with the OECD net zero roadmap by reducing financed emissions.

Equally important is supplier engagement. Since Scope 3 emissions ; those occurring along the value chain can constitute over 70 percent of a firm’s carbon footprint, engagement is non-negotiable. Global leaders such as Unilever and Apple have already begun requiring suppliers to disclose emissions and adopt science-based targets. Businesses that follow suit not only manage risk but also gain transparency into cost drivers and innovation opportunities.

During this medium horizon, pilot projects become laboratories for innovation. A manufacturing company might test low-carbon materials in a single facility; a logistics provider could trial electric fleets on regional routes; a food processor may experiment with regenerative sourcing. These projects de-risk larger investments and allow for measurable learning.

Tools such as the Greenhouse Gas Protocol for emissions accounting, the CDP Supply Chain Program for supplier data, and the OECD’s Climate Policy Simulator for policy forecasting can anchor this stage in credible analytics. By now, firms should publish interim climate progress reports, allowing investors to see movement beyond promises.

Long (3–10 years): full decarbonisation roadmaps, new business models, and policy advocacy

Beyond three years, the focus shifts from experimentation to full-scale transformation. The final phase demands that climate strategy move from incremental improvement to systemic redesign.

Businesses must develop full decarbonization roadmaps, integrating Scope 1, 2, and 3 targets, backed by science-based validation. These roadmaps should identify technology investments, workforce reskilling, and financial instruments that sustain the transition. Aligning with Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) pathways ensures credibility with investors and regulators alike.

At this stage, many firms find that climate alignment opens new revenue streams. Circular models where materials are reused, repaired, or resold can redefine profitability. Service-based models (like product leasing or energy-as-a-service) often reduce waste while building customer loyalty.

Policy advocacy also becomes strategic. Businesses that collaborate with governments and industry alliances can influence the design of carbon markets, renewable incentives, and trade policies. This is especially true for multinationals navigating multiple jurisdictions with uneven regulation. Contributing to OECD consultations or UN business coalitions gives companies a seat at the table rather than leaving them to react after rules are set.

Across all horizons, the message is simple: companies that align early with climate roadmaps not only mitigate risk but seize climate risk and opportunity for business as a growth engine.

Measuring success : KPIs, verification, and reporting

Ambition without metrics is just aspiration. Measuring progress is essential to credibility, especially as investors and regulators demand evidence, not anecdotes.

Businesses should anchor their metrics to globally recognized frameworks. The Science Based Targets initiative verifies whether emissions-reduction trajectories align with a 1.5°C pathway. The GHG Protocol structures emissions into Scope 1 , Scope 2 (purchased energy), and Scope 3 (value chain). The TCFD, ISSB, and ESRS frameworks provide standardized formats for disclosing climate governance, risk management, and metrics.

Verification adds another layer of trust. Third-party auditors from global firms like SGS and DNV GL to local ESG verifiers can certify emissions data and validate reduction claims. Beyond compliance, verification builds investor confidence and shields against accusations of greenwashing.

Community metrics also play a growing role. Earth5R’s digital monitoring of waste reduction, energy savings, and local participation shows that grassroots data can complement corporate ESG reports. For example, a company funding a neighborhood solar project could integrate Earth5R’s verified energy-savings data into its sustainability disclosures. Such partnerships make climate metrics tangible, traceable, and relatable — strengthening both environmental impact and brand narrative.

Ultimately, success must be both quantitative and qualitative: lower emissions, stronger resilience, better stakeholder trust, and a measurable contribution to national and global climate goals.

Risks, trade-offs, and common pitfalls

The road to net zero is fraught with challenges. Businesses often stumble not because of bad intent, but because they misjudge complexity.

The first major pitfall is greenwashing ; making claims without evidence. With scrutiny from regulators and investors intensifying, exaggerated or unverifiable sustainability statements can quickly backfire, damaging credibility and even triggering legal consequences.

Another risk lies in underestimating Scope 3 emissions. Many companies limit focus to direct operations, ignoring the much larger upstream and downstream impacts that lie hidden in supply chains. This omission can lead to incomplete strategies and surprise liabilities when regulations expand.

Poor stakeholder engagement is also costly. Communities, suppliers, and employees are central to any transition. Neglecting them can create resistance, reputational damage, or even project failure. The Earth5R case studies underscore this point: projects succeed only when local actors are involved from design to execution.

Misaligned incentives pose yet another challenge. If executives are rewarded solely for short-term financial performance, climate goals will inevitably slip. Linking part of compensation to emissions-reduction milestones or ESG targets helps align priorities.

Finally, firms must navigate regulatory mismatches between jurisdictions. A company may face strict disclosure laws in the EU but operate in regions with minimal climate regulation. Balancing compliance across markets demands adaptive strategies and continuous policy intelligence.

The key, experts say, is to view climate action as a risk-management discipline rather than a marketing exercise. As one OECD analyst noted, “Every year of delay raises the cost of action by making the adjustment sharper later.”

FAQs on UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications

What are the UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps and why do they matter for businesses?

The UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps outline global strategies to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century. They matter for businesses because they shape regulations, financing priorities, and supply-chain expectations that determine corporate competitiveness.

How do the UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps influence corporate climate strategy?

These frameworks set emission-reduction targets and policy pathways that guide how firms design sustainability goals, allocate capital, and disclose climate risks to investors.

What are the key business implications of the UN climate roadmap?

Businesses face stricter emissions caps, growing disclosure requirements, and new opportunities in renewable energy, adaptation projects, and sustainable supply chains under the UN roadmap.

How does the OECD net-zero roadmap help governments and companies coordinate climate action?

The OECD net-zero roadmap integrates fiscal, trade, and innovation policies to ensure economies decarbonize efficiently. For businesses, it creates policy consistency and clearer market signals for investment.

What scientific evidence supports the UN and OECD climate targets?

Their roadmaps draw on modelling from the IEA, IPCC, and OECD showing that limiting warming to 1.5 °C requires global greenhouse-gas reductions of about 43 % by 2030.

What are the major regulatory risks businesses face under the new climate roadmaps?

Companies will contend with tougher emissions standards, carbon pricing, mandatory climate-risk disclosure (TCFD/ISSB/ESRS), and supply-chain accountability extending to Scope 3 emissions.

How can firms measure and report their emissions in line with global frameworks?

Businesses can use the GHG Protocol for Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, adopt Science-Based Targets (SBTi), and disclose via TCFD, ISSB, or CDP to meet international expectations.

What are the physical climate risks across industries according to the UN climate roadmap?

Extreme weather, floods, and droughts threaten assets, supply chains, and insurance costs. The roadmaps urge firms to model these physical risks using scenario tools such as NGFS or IEA pathways.

What new market opportunities emerge from the OECD net-zero roadmap?

Clean-energy technologies, green finance, circular-economy models, and resilience solutions are key growth areas highlighted by OECD and UN analyses.

How should businesses integrate internal carbon pricing into their operations?

By assigning an internal price to each tonne of CO₂, firms can evaluate projects, guide investment decisions, and prepare for external carbon-market exposure.

What lessons do Earth5R case studies offer for corporate sustainability?

Earth5R’s community pilots in India show that local climate action — from composting and water harvesting to carbon-neutral neighborhoods — can strengthen supply chains and social license for businesses.

How can local community initiatives align with global climate roadmaps?

Projects such as Earth5R’s Rural Sustainability Model or river clean-ups translate global goals into local metrics, offering replicable templates for corporate-community partnerships.

Which business sectors face the highest transition risk under the climate roadmaps?

Energy, heavy industry, agriculture, and finance are most exposed due to their emissions intensity and regulatory oversight — but they also stand to gain from innovation and efficiency.

What KPIs should companies track to align with climate roadmaps?

Key indicators include CO₂e intensity, Scope 1/2/3 coverage, carbon-price sensitivity, physical-risk exposure, and progress against verified decarbonization targets.

How can financial institutions apply climate-scenario analysis and stress testing?

Banks and investors can use NGFS or OECD models to test how portfolios perform under different carbon-price or warming scenarios, revealing exposure to stranded assets.

What are the economic benefits of accelerated climate action according to OECD and UNDP studies?

OECD-UNDP modelling shows that faster decarbonization could boost global GDP by up to 0.2 % by 2040 and 3 % by 2050, while avoiding costly climate damages.

How can companies verify and communicate their progress credibly?

Third-party verification, transparent data reporting, and partnerships with certified monitoring systems like Earth5R’s digital tracking tools ensure credibility and stakeholder trust.

What are the common pitfalls companies face in implementing climate strategies?

Greenwashing, ignoring Scope 3 emissions, weak stakeholder engagement, and inconsistent policies across jurisdictions are leading causes of credibility loss.

How can SMEs participate in the global net-zero transition?

Small and medium enterprises can join local carbon-neutral programs, adopt low-cost energy-efficiency tools, and collaborate with larger corporates on shared emissions-reduction goals.

What practical steps should businesses take today to align with the UN and OECD climate roadmaps?

Start by mapping emissions, setting short- and long-term targets, reallocating capex to green assets, engaging suppliers, and publishing transparent progress updates.

From Roadmaps to Results: Turning Climate Commitments into Business Action

The evidence is unequivocal. Scientific modeling, economic analysis, and ground-level experiments all converge on the same insight: aligning with climate roadmaps is not just ethical, it’s economically rational. From the OECD’s macroeconomic forecasts to Earth5R’s measurable community pilots, the message is consistent. UN and OECD Climate Roadmaps: Key Business Implications translate into a practical framework that every company can apply, step by step.

Start by understanding your footprint and governance gaps. Engage your suppliers and your communities. Set measurable targets. Verify them. Then scale innovation into your products, services, and culture. Each small step compounds into systemic change.

For readers ready to act, consider downloading a one-page checklist summarizing these steps, or join a pilot program inspired by Earth5R’s local partnerships. Alternatively, request a sector-specific expansion to see how your industry can tailor these global roadmaps into actionable plans.

The transition to net zero is already underway. The only real question is whether your organization will follow the curve or help define it.

Authored by- Sneha Reji