Rooted in Resistance, Growing in Regeneration

Across the verdant fields and forested margins of rural India, a silent revolution is taking root—led not by corporations or policymakers, but by the hands of rural women. These women, often unseen and under-credited in the agricultural narrative, are nurturing a regenerative food system that challenges both ecological degradation and entrenched patriarchy. Their agroecological practices are more than methods of cultivation; they are acts of resistance, renewal, and resilience.

Agroecology—defined by the FAO as “an integrated approach that applies ecological and social concepts to the design and management of sustainable agriculture”—offers a powerful framework for understanding this movement. It is both a science and a social movement, and in India, it is increasingly being shaped by rural women farmers who are reclaiming control over food, land, and local economies. Their leadership is not accidental. It emerges from decades of marginalization, environmental decline, and systemic gender inequality.

As mainstream agriculture becomes increasingly chemical-intensive, water-hungry, and corporate-driven, women-led agroecological initiatives offer a grounded, people-centric alternative. These women are embracing practices like composting, mixed cropping, and natural farming not only to heal the soil but to transform the socioeconomic structures around them.

This uprising is particularly urgent in the face of India’s agrarian crisis. According to Oxfam India, while women comprise over 70% of the agricultural workforce, they own less than 13% of land. Despite these systemic hurdles, they are mobilizing collective knowledge, reviving traditional ecological practices, and asserting their place as stewards of the land. Their efforts challenge monocultures, market dependency, and extractive farming models, replacing them with seed sovereignty, biodiversity, and community-supported agriculture.

Movements like the Deccan Development Society in Telangana and Navdanya led by Dr. Vandana Shiva have long championed this transformation, spotlighting how women’s indigenous knowledge and community networks can regenerate degraded soils, preserve climate-resilient crops, and promote food sovereignty.

Meanwhile, grassroots innovations from organizations like Earth5R are empowering women with skills in urban farming, composting, and eco-entrepreneurship, bridging the rural-urban divide in sustainability.

In the face of climate change, land degradation, and rural poverty, this agroecological uprising provides a hopeful, locally-rooted solution. It places rural women at the forefront of a transition that is ecological, economic, and emancipatory.

Agroecology and Gender: A Natural Alignment

Agroecology is not merely a method of farming—it is a way of life that embodies care, reciprocity, and sustainability. These values naturally resonate with the lived experiences of rural Indian women, whose daily interactions with soil, water, seeds, and food systems have historically been grounded in interconnectedness and nurturing relationships with nature. The synergy between agroecological principles and gender roles is not coincidental; it is rooted in centuries of practice, resilience, and gendered knowledge systems.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), agroecology rests on principles like diversity, synergy, efficiency, recycling, and co-creation of knowledge—all of which reflect the kinds of informal, intergenerational wisdom rural women have preserved. Women’s agroecological contributions are often invisible in policy frameworks, but they are central to climate resilience, soil restoration, and community food systems. This alignment makes agroecology not just a viable strategy, but a gender-just pathway to sustainable development.

Rural Indian women are often the first to experience the impacts of climate change, from erratic rainfall and droughts to crop failure and rising food prices. Yet, they also possess the practical and traditional knowledge needed to adapt and respond. For instance, their expertise in seed selection, intercropping, and pest control using natural ingredients has long been integral to low-input, high-diversity farming. Studies like this one by IIED highlight how agroecological practices help women contest patriarchal norms and gain agency over production systems.

In many parts of India, agroecology has allowed women to shift from being subsistence laborers to decision-makers and knowledge holders. Initiatives like Andhra Pradesh Community-managed Natural Farming (APCNF) and programs supported by Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) show how women-led agroecology not only improves yields and nutrition, but also transforms gender relations, enhances collective leadership, and promotes social equity.

The alignment becomes even clearer when one considers how agroecology moves away from extractive agricultural models. Unlike conventional farming, which relies on chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and mono-cropping, agroecological systems value local inputs, biodiversity, and community participation—spheres where rural women have historically led. Their ability to draw on eco-cultural knowledge and adapt to localized ecosystems makes them indispensable to the agroecological transition.

Moreover, this gendered alignment is not only practical but also political. Feminist agroecology, as advocated by networks like La Via Campesina and MAKAAM (Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch), recognizes that transforming agriculture requires confronting structural gender inequalities, such as the lack of land rights, credit, and institutional support for women farmers.

In this context, agroecology emerges as a tool of empowerment—enabling women not just to farm more sustainably, but to reshape rural economies, challenge social hierarchies, and reclaim autonomy over natural resources and livelihoods. The natural alignment between gender and agroecology is thus not only ecological—it is deeply emancipatory.

The Feminization of Indian Agriculture

Over the past few decades, India has witnessed a quiet yet profound transformation in its agricultural landscape—one marked by the increasing participation of women in farming. This phenomenon, often referred to as the “feminization of agriculture”, reflects not only a demographic shift but also a deeper structural transformation in rural economies.

According to a 2018 report by Oxfam India, women constitute over 70% of the agricultural workforce in India, contributing significantly as cultivators, agricultural laborers, and unpaid family workers. However, despite their indispensable roles in sowing, transplanting, weeding, harvesting, and post-harvest processing, they remain marginalized in policy discourse, lacking land ownership, decision-making authority, and access to credit and extension services.

This feminization is, paradoxically, both a result of male outmigration and an indicator of women’s increasing agency. As men move to urban centers in search of non-farm employment, rural women are left to manage agricultural operations independently. This shift, documented in studies like this one by IFPRI, has led to a scenario where women are not just supporting farming—they are leading it.

Yet, the structural conditions remain deeply unequal. As per the NSSO 2019, only 12.8% of land holdings are owned by women, despite their overwhelming participation in farming. Without formal ownership, women are often excluded from government schemes like PM-KISAN and find it difficult to access institutional credit, crop insurance, or agricultural training.

This invisibility perpetuates what researchers call the “feminization of responsibility without power”—a situation where women bear the burden of food production without the recognition or resources to support their work. Organizations such as MAKAAM (Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch) have been vocal in challenging this disparity, advocating for women to be legally recognized as “farmers”, not merely as helpers or laborers.

Despite the odds, rural women are reclaiming their identities as cultivators and change-makers. Across states like Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal, women’s collectives are forming Self-Help Groups (SHGs), Producer Companies, and Farmer Field Schools to share knowledge, save seeds, market their produce, and transition to agroecological methods. These shifts are documented in participatory studies like those by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN), which explore how women are navigating both ecological and gender transitions.

The feminization of agriculture is thus not merely a statistic—it is a socio-political reality that demands rethinking how we define and support farming in India. It offers an opportunity to build a more inclusive and sustainable agricultural future, one that honors the knowledge, labor, and leadership of women of the soil.

Seeds of Change: Women as Guardians of Biodiversity

In the heart of rural India, where agriculture remains intimately linked to tradition and ecology, women have long served as custodians of seed biodiversity. Long before the rise of industrial agriculture and genetically modified crops, it was women who selected, saved, exchanged, and planted seeds — not merely as a farming task but as a cultural and ecological responsibility. Today, as the world grapples with the loss of crop diversity and the perils of seed monopolies, these women stand at the frontlines of a quiet revolution in seed sovereignty.

Traditional seed saving, often passed down through oral knowledge systems, is a time-tested practice that preserves genetic diversity, ensures climate resilience, and sustains local food cultures. Yet, this vital work has been steadily eroded by the spread of commercial hybrid seeds, patent regimes, and agribusiness-led monocultures. According to Navdanya, over 75% of agro-biodiversity has been lost in the past century, driven by corporate control and uniform farming systems. In contrast, indigenous seed keepers—most of whom are women—continue to protect and cultivate heirloom, region-specific varieties adapted to local soils and climatic conditions.

Take, for instance, the Deccan Development Society (DDS), where Dalit women farmers in Telangana have created over 80 community-managed seed banks, preserving more than 80 varieties of millets, pulses, and vegetables. These seed banks not only secure food sovereignty but also represent a political reclaiming of knowledge and control over agriculture. Through their Community Media Trust, these women document their work, create seed festivals, and educate others about agroecological practices.

Similarly, women-led seed-saving movements in Chhattisgarh and Odisha are revitalizing traditional varieties of rice, brinjal, and millet that are drought-resistant, pest-tolerant, and nutritionally rich—traits increasingly crucial in the age of climate change and soil degradation. By prioritizing biodiversity over uniformity, these women are creating seed systems that are both ecologically sound and economically empowering.

At the global level, initiatives such as the Seed Freedom campaign and La Via Campesina have highlighted the importance of free seed exchange networks, often powered by women’s collectives. These networks not only defy corporate monopolies but also celebrate seeds as living heritage—sources of nutrition, memory, resistance, and regeneration.

Moreover, the work of women as seed savers is deeply embedded in the ethos of agroecology. Agroecological farming depends on polyvarietal cropping systems, open-pollinated seeds, and local ecological knowledge—domains where women are key innovators. As documented in this FAO report on women and biodiversity, their seed choices are often guided not only by yield but by taste, storability, medicinal value, and cultural preferences—criteria ignored by commercial breeders but essential to community well-being.

Yet, their role remains undervalued. Most formal seed policies in India do not recognize women’s seed systems, nor do they support decentralized, community-led seed banks. Instead, programs like the National Seed Policy often prioritize certified seeds and commercial breeders, leaving little room for the nuanced, diverse seed-saving ecosystems nurtured by rural women.

Despite these barriers, women continue to sow seeds of change—defying industrial pressures, restoring native crops, and nurturing biodiversity from the ground up. In doing so, they are not only protecting India’s agroecological future but also reclaiming their ancestral role as stewards of life.

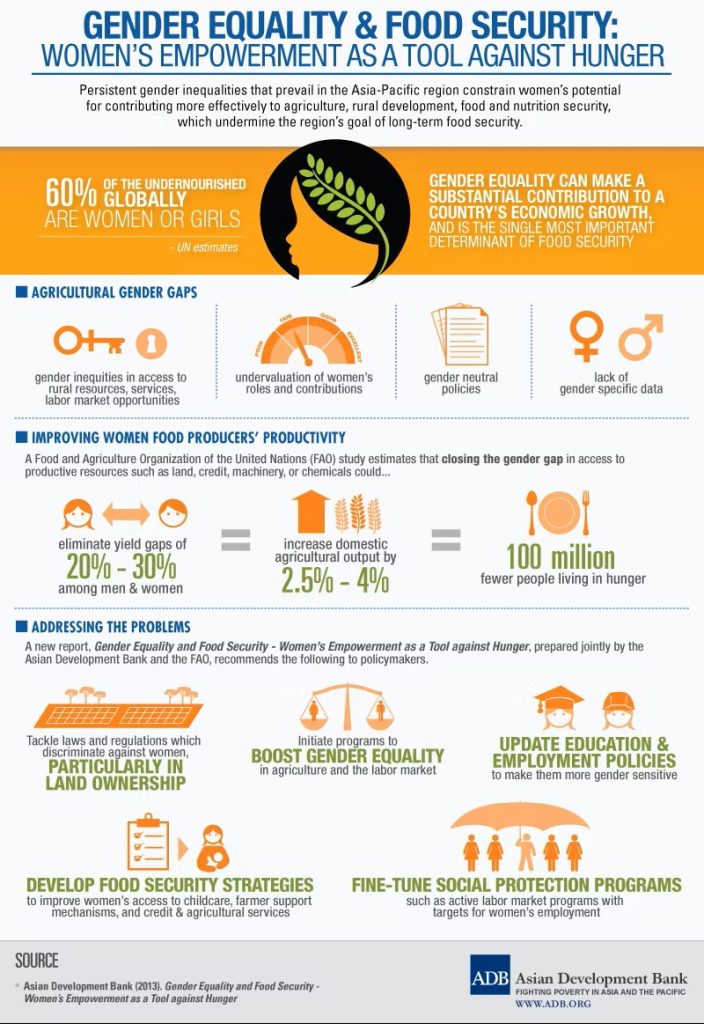

This infographic highlights how gender inequality undermines food security, showing that 60% of the undernourished globally are women or girls. It emphasizes the need to close agricultural gender gaps to boost women’s productivity and drive sustainable economic growth—an urgent call that resonates deeply with rural Indian women leading the agroecological revolution.

Earth5R Case Studies: Empowering Women Through Sustainable Agriculture

At the intersection of climate action, social equity, and grassroots empowerment stands Earth5R, a citizen-led environmental organization that has been transforming communities across India and beyond. With a focus on sustainability, resilience, and regenerative development, Earth5R’s programs actively empower rural and semi-urban women to become ecopreneurs, agroecological leaders, and change agents within their local ecosystems.

Earth5R’s BlueCities initiative, which integrates climate-smart agriculture, waste management, and natural resource restoration, has been instrumental in linking environmental regeneration to livelihood creation for women. One of the core pillars of Earth5R’s approach is the training and capacity-building of women in sustainable farming practices, enabling them to move from being passive beneficiaries to active climate leaders.

In rural Maharashtra, for example, Earth5R collaborated with local self-help groups (SHGs) to launch a community composting and organic farming initiative. Women were trained in vermicomposting, bioenzyme preparation, and zero-waste farming techniques—skills that not only improved soil health but also generated marketable eco-products. The organic produce and compost generated were sold to local markets and city retailers, creating a new stream of green income for participating women.

These training sessions align with Earth5R’s circular economy framework, where waste from one process becomes input for another. As seen in this Earth5R composting case study in Mumbai, women-led community groups were able to divert food waste from landfills and transform it into valuable agricultural input—contributing both to climate mitigation and economic empowerment.

In another project in Tamil Nadu, Earth5R worked with women farmers to revive traditional millet cultivation using agroecological principles. Participants were taught to reduce chemical input, improve water use efficiency, and intercrop with legumes and vegetables to boost nutrition and soil fertility. This effort not only restored climate-resilient crops but also improved household food security, especially in drought-prone areas. Millets, declared as “nutri-cereals” by the Government of India, are now being promoted as a cornerstone of sustainable diets—aligning perfectly with Earth5R’s long-standing advocacy for local food systems.

Beyond farming, Earth5R’s work includes educating women on financial literacy, eco-enterprise development, and community leadership. The organization encourages women to take leadership roles in climate resilience planning, whether through creating urban gardens, managing decentralized waste units, or becoming trainers themselves under Earth5R’s “Train the Trainer” model. This model has allowed women to replicate and scale projects across different states—building a web of peer-to-peer knowledge exchange and localized action.

Furthermore, Earth5R’s global citizen science network provides a platform for documenting these grassroots successes. Through their mobile app and digital interface, rural women can log their sustainability efforts, track impacts, and connect with policy advocates, NGOs, and CSR partners to amplify their reach. The model exemplifies how digital tools, when made accessible, can democratize sustainability and connect rural voices to global climate conversations.

What makes Earth5R’s approach particularly powerful is its commitment to intersectionality. Their programs do not isolate environmental issues from gender, poverty, or development—but rather weave them into a holistic, community-driven framework. By investing in women, Earth5R is not just creating greener farms—it is cultivating climate resilience, economic justice, and community regeneration from the soil upward.

From Kitchen Gardens to Community Farming: Cultivating Food Sovereignty

What begins as a humble kitchen garden behind a mud-walled home often grows into a movement. Across rural India, women are transforming private plots into public models of food sovereignty—a concept that emphasizes the right of communities to control their own food systems, prioritizing local production, traditional knowledge, and ecological integrity.

Initiatives like the National Nutrition Mission (Poshan Abhiyaan) have recognized the value of home-grown food for combating malnutrition and hidden hunger. In states like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Assam, women-led Self-Help Groups (SHGs) have scaled kitchen gardens into nutrition-sensitive farming systems, often supported by local NGOs and government extension programs.

But the real shift occurs when these gardens expand beyond the household. Across the country, collectives of women are organizing into community farming groups, pooling land, seeds, labor, and water to grow food not just for their families, but for entire villages. These collective farms, such as those facilitated by the Deccan Development Society and SEWA Bharat, enable women to cultivate millets, pulses, indigenous rice, and vegetables using organic and permaculture principles, while also asserting their role in land stewardship.

Such models are foundational to food sovereignty, a term popularized by La Via Campesina, which advocates for the rights of small farmers, especially women, to shape agricultural policies and local food economies. Unlike food security, which may still rely on imported or industrial food, food sovereignty emphasizes control over production, seed freedom, and market access for local producers.

One powerful example of this shift can be found in Jharkhand, where Adivasi women supported by grassroots organizations have transformed kitchen gardens into community food forests, reintroducing over 50 indigenous species of vegetables and legumes. These efforts not only ensure year-round nutrition but also restore degraded commons, regenerate biodiversity, and reinforce cultural practices tied to food and the land.

Earth5R has similarly supported this transition through its urban-rural linkages—enabling women in peri-urban regions to cultivate gardens that supply local markets, schools, and hospitals with fresh, chemical-free produce. Their focus on decentralized farming and community resilience ties directly into the broader food sovereignty movement.

Ultimately, the shift from kitchen gardens to community farms is more than a scaling-up of land use—it is a scaling-up of agency, solidarity, and ecological intelligence. By anchoring food systems in women’s hands, India’s rural communities are cultivating not just crops, but a radical vision of self-determination and sustainability.

Eco-Enterprises and Green Livelihoods: Rural Women as Climate Entrepreneurs

As the world turns toward sustainable economies, rural Indian women are quietly becoming climate entrepreneurs, turning agroecological knowledge into thriving eco-enterprises. These enterprises are not just income-generating—they are climate-resilient, community-rooted, and environmentally regenerative. In a context where women face limited access to formal employment, eco-enterprise offers a transformative pathway to both financial independence and environmental stewardship.

Women are now leading the production of organic inputs such as vermicompost, bioenzymes, liquid fertilizers, and natural pesticides, which are increasingly in demand among smallholder farmers transitioning to chemical-free farming. Organizations like Earth5R have trained hundreds of women in creating and marketing these products through green micro-enterprises, as seen in their initiatives in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. These eco-products not only replace chemical alternatives but also promote soil health and carbon sequestration, making them vital in the fight against climate change.

In Jharkhand, for example, women trained in vermicomposting and natural farming have launched home-based businesses that supply compost to local farms. Similarly, in Tamil Nadu, women Self-Help Groups are producing organic repellents, herbal teas, and value-added food products like millets and pickles, often selling them through local markets or digital platforms supported by NGOs.

Eco-enterprises also include upcycled products made from agricultural waste, such as agro-waste paper, biodegradable packaging, and textiles. Initiatives like EcoKaari and Barefoot College have shown how women artisans can lead the way in creating circular economy models that reduce pollution and generate sustainable income.

Furthermore, women’s collectives like those under SEWA, Timbaktu Collective, and Navdanya are creating farmer-producer organizations (FPOs) that market certified organic and heirloom produce, giving women access to premium markets and fair trade networks. These models challenge the extractive supply chains dominated by corporate agribusiness and bring economic value directly back to producers.

By integrating climate adaptation into their business models, these women-led eco-enterprises also align with the green jobs agenda promoted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and SDG 13 on Climate Action. Their work shows that climate mitigation is not just the domain of large-scale technology—it can also be achieved through community knowledge, sustainable livelihoods, and micro-level innovation.

Rural women are no longer just producers; they are entrepreneurs, educators, and climate leaders—building green economies that restore the earth and empower their communities.

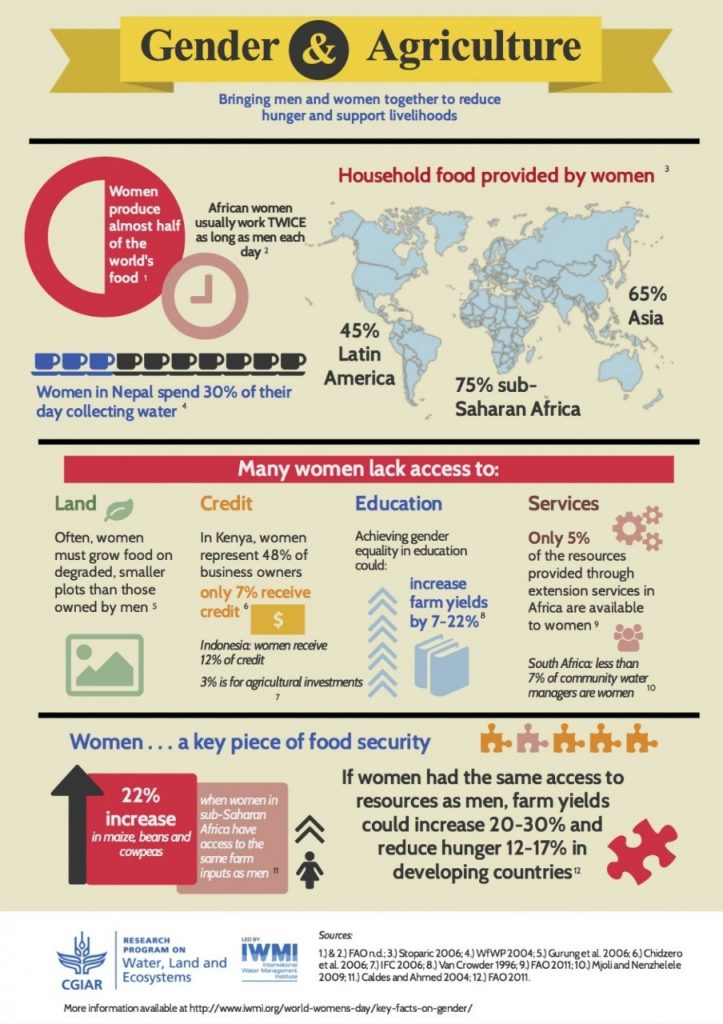

This infographic underscores the vital yet undervalued role women play in global food production, providing up to 75% of household food in some regions. Despite this, rural women—like those in India’s agroecological movement—face persistent barriers to land, credit, education, and essential services.

Breaking Barriers: Land Rights, Education, and Recognition

Despite their growing leadership in agriculture and sustainability, rural Indian women continue to face systemic obstacles that hinder their full participation and recognition as farmers. The most critical of these is land ownership. According to India’s Agriculture Census 2015-16, women account for just 13.9% of operational landholders, a figure that severely limits their access to institutional credit, government schemes, and decision-making authority in agricultural planning.

This lack of legal land rights perpetuates a cycle of economic insecurity and social invisibility. Without land titles, women are often excluded from subsidies under schemes like PM-KISAN, and cannot secure loans, irrigation equipment, or crop insurance. The Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch (MAKAAM) has been at the forefront of demanding legal recognition of women as farmers, pushing for gender-disaggregated data, inheritance reforms, and inclusive policies that prioritize land access for single, widowed, and tribal women.

Education is another key barrier. Many rural women have limited access to formal education and agricultural extension services, which are often designed for male landowners and conducted in inaccessible formats or locations. However, women’s collectives and grassroots NGOs are working to close this gap by offering context-specific, vernacular-language training on agroecology, entrepreneurship, climate resilience, and digital skills.

Programs like Digital Green are using video-based training tools to reach women farmers with visual, peer-to-peer learning methods that resonate in low-literacy settings. Meanwhile, Earth5R’s “Train the Trainer” model creates localized learning hubs, where women are equipped not only with sustainable farming practices but also with leadership skills and the confidence to educate others.

The lack of institutional recognition is perhaps the most insidious challenge. Even though women are often responsible for a majority of farming tasks, they are rarely listed on land records or considered in agricultural statistics. This “invisibility” has been documented in UN Women’s reports, which highlight how the feminization of labor is not matched by the feminization of rights.

Despite these barriers, women are claiming space in the agricultural landscape through collective action and advocacy. In Uttar Pradesh, women’s federations have begun filing joint applications for land leases under the Forest Rights Act. In Andhra Pradesh, the Community Managed Natural Farming (CMNF) program actively prioritizes women-headed households for training and land support.

Breaking these barriers is not just a matter of fairness—it’s a prerequisite for sustainability. Studies show that when women have secure land rights and access to resources, agricultural productivity increases, nutrition improves, and ecological practices flourish.

Community, Care, and Climate Resilience — The Women-Led Model

At the heart of rural India’s agroecological revolution lies a transformative force often overlooked in policy circles: collective care. Unlike conventional agribusiness models that emphasize individual profit and market competition, women-led agroecological systems are rooted in mutual support, community well-being, and ecological balance.

This approach stems from women’s traditional roles as caregivers, seed savers, and knowledge holders—roles that have long shaped how communities interact with land, water, and food. Today, these values are being reasserted in the face of climate change, agrarian distress, and ecological degradation, offering a blueprint for a more resilient and regenerative rural economy.

In Andhra Pradesh, the Community Managed Natural Farming (CMNF) program, spearheaded by RySS (Rythu Sadhikara Samstha), has enrolled over a million farmers, most of them women, in adopting chemical-free farming practices grounded in local microbial cultures, mulching, intercropping, and soil regeneration. This model goes beyond crop yields—it fosters collective decision-making, peer learning, and women-led leadership structures that strengthen social fabric while building ecological resilience, as explained in this article on Andhra’s natural farming revolution.

Similarly, Earth5R’s BlueCitizen model builds hyperlocal sustainability networks where women engage not only in sustainable farming but also in waste management, waterbody rejuvenation, and community-level climate education. Through initiatives like these, Earth5R empowers women to become citizen scientists, micro-entrepreneurs, and local trainers, proving that sustainability thrives when built from the ground up, with women at the core of environmental change.

A major aspect of this care-based model is the revival of indigenous seed systems. Women’s seed banks across Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Telangana have played a crucial role in conserving climate-resilient varieties such as drought-tolerant millets, flood-resistant rice, and pest-resistant pulses. Initiatives like Navdanya have documented how women-led seed networks support biodiversity conservation and shield rural communities from the risks of commercial seed dependency.

Beyond production, women’s groups are instrumental in ensuring community food access through kitchen gardens, community kitchens, and reforms in the public distribution system (PDS). In Madhya Pradesh, the Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana (MKSP), a flagship initiative under the National Rural Livelihoods Mission, has enabled women to grow their own food, share surplus with neighbors, and lead nutrition awareness campaigns at the village level.

These women-centered agroecological systems are inherently resilient to climate stress, particularly through localized food chains, rainwater harvesting, and crop diversification. These strategies help reduce dependency on external markets and inputs. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), enhancing women’s roles in agriculture and natural resource governance could increase agricultural output in developing countries by as much as 30 percent, a testament to their pivotal role in food systems transformation.

Ultimately, this is not just a story of women participating in agroecology—it is a story of how agroecology itself is being reshaped by women’s ethics of care, cooperation, and community resilience.

Toward a Feminist Agroecology: Policy Shifts and the Road Ahead

To sustain and scale the movement led by rural women, India must adopt a feminist lens in its agricultural and climate policies—one that centers women’s knowledge, needs, and rights in every aspect of rural transformation. The current policy framework, while increasingly open to agroecology, remains largely gender-neutral and biased toward input-intensive, male-dominated models of farming.

A feminist agroecology demands a fundamental shift: from treating women as beneficiaries to recognizing them as primary actors, decision-makers, and innovators. It means reimagining agricultural development through the lens of intersectionality, land justice, and ecological sovereignty.

Several grassroots organizations and networks have outlined this roadmap. The MAKAAM (Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch), for instance, has published a comprehensive charter calling for:

- Joint land titles for women farmers and cultivators.

- Gender-disaggregated agricultural data.

- Special agricultural credit lines for women-led eco-enterprises.

- Capacity-building for women in sustainable practices and digital tools.

- Representation of women in decision-making at panchayat, block, and state levels.

At the global level, the Nyéléni Declaration on Feminist Agroecology provides a powerful framework that connects food sovereignty, gender justice, and ecological regeneration, calling on states to recognize the political power of care work and rural women’s contributions to climate solutions.

India’s agroecology policies must be informed by these feminist principles. This includes expanding programs like MKSP and CMNF, ensuring they include gender audits, and increasing budgetary allocations for women-led sustainable farming initiatives. A National Mission on Feminist Agroecology, modeled after the success of Andhra Pradesh’s ZBNF, could institutionalize women’s leadership in climate-smart agriculture across the country.

Digital inclusion is also key. With platforms like Digital Green, e-NAM, and Kisan Suvidha expanding, targeted interventions are needed to ensure that rural women are digitally literate, market-connected, and e-governance-ready.

A feminist agroecological transition is not a utopian vision—it is a policy imperative for an equitable, food-secure, and climate-resilient India. Recognizing and investing in the leadership of rural women is not only just—it is smart, sustainable, and long overdue.

FAQs on Women of the Soil: Rural Indian Women Leading an Agroecological Uprising

What is agroecology and how is it different from conventional farming?

Agroecology is a sustainable farming approach that integrates ecological principles with traditional agricultural practices. Unlike conventional farming, it avoids chemical inputs and promotes biodiversity, soil health, and community participation.

Why are rural women central to the agroecological movement in India?

Rural women have traditionally been custodians of seeds, soil, and food. Their deep knowledge of local ecosystems and community networks makes them natural leaders in sustainable agriculture.

What does the term “Women of the Soil” signify?

It highlights the intrinsic connection rural women share with the land—physically, spiritually, and socially—and their pivotal role in nurturing both soil and society.

How has the feminization of agriculture affected India’s rural economy?

With increasing male migration to urban areas, women now form a majority of the agricultural workforce. They handle everything from sowing and weeding to marketing and seed preservation.

What is food sovereignty and how are women promoting it?

Food sovereignty is the right of communities to control their own food systems. Women promote it by cultivating local, organic food through kitchen gardens and collective farms, preserving indigenous seeds, and resisting corporate food systems.

What are kitchen gardens and how do they contribute to nutrition?

Kitchen gardens are small, household-level gardens maintained by women. They provide diverse and nutrient-rich food, addressing malnutrition and dietary diversity at the grassroots level.

How are rural women acting as climate entrepreneurs?

They’re starting eco-enterprises like compost production, organic input supply, bioenzyme manufacturing, and sustainable handicrafts—generating green livelihoods while addressing environmental challenges.

What role does Earth5R play in empowering rural women?

Earth5R trains women in sustainable practices like organic farming, waste management, and community resilience. It also helps build local supply chains and promotes environmental entrepreneurship.

Why is access to land and land rights important for rural women?

Without land ownership, women face barriers to credit, government schemes, and decision-making. Secure land rights empower them economically and socially.

What are some examples of successful women-led agroecological movements in India?

Movements like the Deccan Development Society in Telangana, Navdanya’s seed-saving initiatives, and the Kudumbashree collective in Kerala are key examples of rural women leading change.

How do agroecological practices contribute to climate resilience?

They build healthy soils, conserve water, enhance biodiversity, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions—making farms more adaptable to climate change.

Are there any government schemes supporting women in agriculture?

Yes, schemes like Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana (MKSP) and the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) support women farmers with training, resources, and collective formation.

What are community seed banks and how do women manage them?

Community seed banks are local repositories of indigenous seeds. Women preserve, share, and exchange seeds—ensuring biodiversity and seed sovereignty.

What barriers do rural women face in agriculture?

They face limited access to land, credit, education, technology, markets, and decision-making power due to entrenched gender norms and structural inequalities.

What is the significance of collective farming for women?

Collective farming enables women to pool land and resources, access markets, share knowledge, and exercise greater economic and social agency.

How do eco-enterprises impact rural development?

Eco-enterprises generate income while promoting sustainability. They create jobs, revive local economies, and reduce ecological footprints.

What is the link between agroecology and indigenous knowledge?

Agroecology thrives on traditional knowledge systems—crop rotation, seed preservation, natural pest control—which are often preserved and passed on by women.

How do women’s SHGs contribute to agroecological practices?

Self-Help Groups facilitate training, seed sharing, and group farming. They also provide a support system for women to experiment and innovate sustainably.

Can agroecology address India’s growing food and nutrition crisis?

Yes, agroecology enhances food quality, diversity, and accessibility while restoring ecological balance—making it a sustainable alternative to industrial agriculture.

How can individuals support women-led agroecology?

You can support by buying local organic produce, donating to grassroots initiatives, advocating for gender-just policies, and amplifying the voices of rural women.

Join the Movement: Empower Women, Regrow the Earth

To truly transform India’s food systems, we must recognize rural women as leaders of ecological change—not just participants. Support women-led agroecology by advocating for inclusive policies, amplifying grassroots innovations, and investing in community-driven, climate-resilient farming models. It’s time to grow food, justice, and equity—together.

-Authored By Pragna Chakraborty