Earth5R Podcasts: Greenwashing

In Earth5R’s second edition of its Sustainable Futures podcast series titled “Greenwashing, governance and Growth,” Founder and Environmentalist Saurabh Gupta is in conversation with John Pabon, Sustainability consultant, speaker, UN advisor, and author of the Great Greenwashing.’

While discussing John Pabon’s career trajectory from working with the United Nations to opening his own environmental consultancy group in Australia, the conversation focuses on translating theory to pratical sustainable strategies for individuals interested in pursuing a career in sustainability. The second half of the podcast explains John Pabon’s theory of change, before unpacking the key concept of Greenwashing. This section focuses on concrete strategies for consumers and audience to recognise greenwashing and transition to a more sustainable livelihood.

Chapters

- From Theory to Practical Sustainability Strategies

- Working with the United Nations: Insights and Experiences

- Sustainable Business Practices: Case Studies

- Theory of Change: Effective Communication

- Critical Perspectives on Greenwashing

- The Great Greenwashing

Conversation

Saurabh: Welcome everyone on Sustainable Futures podcast, our guest today is John Pabon, who is from Australia. John is a sustainability author, hes written book, which is about greenwashing, particularly and his book is very interesting they have a lot of business case studies, which is not only helping communities but it’s also helping businesses, how they can enhance the way they communicate their sustainability and how they can enhance the way they do their sustainability at workplace.

Also, John has worked with the United Nations and he has pretty long track record in consulting as well. So over to John. John, would you like to give a quick introduction of yourself.

John: Sure thing. Thanks for that. You’ve covered most of it, but I guess I’ve been in the sustainability space for about 20 years, but even before it was called sustainability, I think we still called it CSR way back when.

So I, as you mentioned, started my career at the United Nations that was always the goal was to work there and I did for quite a bit of time, but after speaking with some mentors there. People recommended I maybe go out into the private sector and then come back to the UN a little bit later in life with I’ve just started to do now as a consultant for the UN after many years outside the organization. But I’ve worked in the consulting space with the likes of McKinsey, AC Nielsen and BSR, who’s sort of the McKinsey of the sustainability world.

And I fell into sustainability kind of by accident. So I took a trip to China, just on a vacation, went back to New York where I was living at the time during the height of the global recession, and it was very tough to live in New York. So I thought, let’s go to China and try it out.

So I moved there for a little bit of time and needed to figure out how do I use all of this experience in the public sector, the UN and public sector clients and consulting in a very commercial city. So that’s how I landed in the type of sustainability work that I do, which I’m sure we’ll get into, which is more working with private sector clients.

Saurabh: So, John, during your track record, it has been 20 years you’re into sustainability. So what are some of the important lessons that you learned in corporate sustainability and urban development? Would you like to share some of the learnings? Absolutely. I think the biggest one, and this is something that is still a learning that we’re trying to get across to a lot of people, especially people that may not be in sustainability, is that the work we do is not an on-off switch.

John: There’s a lot of gray area, a lot of nuance, and it is a transition. This is why we use language like a just transition or sustainable development, because we know that it’s going to evolve and take a long time. I would love for things to be done now and to be out of a job, and I’m sure a lot of people would love for us to have a perfect world, but it’s going to take a very long time.

This is why we use language like a just transition or sustainable development, because we know that it’s going to evolve and take a long time.

So that’s the biggest learning, I think, for me personally, certainly in this space, is how long these changes take, but also understanding that, especially in the private sector, there is so much movement in a positive direction that that gives me hope for the future, or else I wouldn’t do what I do. I’ve seen positive change, and I continue to see that positive change. I wish more companies would talk about it, because that would get even more companies and individuals along for this fight that we’re all in to save the planet.

Saurabh: Yeah, interesting. So John, what were some of the practical, because you’re an author and you have a lot of theories of change, and we’ll come to your theory of change a bit later on, but also would like to know that in early days of your sustainability career, what were the steps you took to move from theoretical, or I would say that the theory to practicing sustainability, which is more on strategic level or more on practical level? It does take a lot of learning. And I think the interesting thing is when I started off in sustainability, it wasn’t really taught in school.

John:I know today people will come out of school or they’ll be going through school with degrees in sustainability or in environmental science or something related to saving the planet or humanity. And that’s amazing. I love to see that.

But back in my day, if I’m going to sound like an old person, that didn’t really exist. Maybe people would be scientists, but that’s about as far as it would be. So it was a lot of learning on the job.

And I think even today, for those that are going through school now, yes, you have your practical learning, but the majority of what you will learn and how things actually work happens in the day-to-day job. And it’s not just sustainability, that’s probably every field. So there’s, of course, the book stuff that you learn, and then there’s the actual stuff that you learn afterwards.

John during his time working in the UNFCCC Secretariat, Istanbul, 2009

And that has taken many, many years to come to terms with, 20 years of lots of learning. And as well, in our space, things are changing so quickly that I think from a very practical standpoint, it’s important for people to niche down as much as possible in our space. We would love to do everything, of course, but it’s very, very impractical to say you’re going to do everything within sustainability.

You need to really hone in on a particular area. So for me, for example, my area now is more on the governance side of things. And even within that, focusing down into communications, greenwashing, and materiality.

So that’s so niche. And even within that, I have a very hard time keeping up with all the changes going on, especially in the regulatory environment. So for everybody listening, make sure that you have your specialization as much as possible.And believe me, that will be enough to keep you entertained for a long time.

Saurabh: So, John, when did you realize, in 20 years of your career, when did you realize that you wanted to niche down to communication or governance? Before that, though, my decade living in China, I worked on the social side of sustainability. So working a lot with factories, in and out of lots of factories, developing worker betterment programs.

John: So you can see just from those two periods of my sustainability career, a massive switch in terms of what I focused on. So even though I told people, you know, niche down, that doesn’t mean you have to be doing that the rest of your career, you can always evolve and change.

So coming back to China, when you said that you were working in factories and working with different companies. So what was the kind of sustainability work that you did over there? Can you elaborate a bit more on that? Sure. So a lot of, and this was probably because of the period of time when I worked there, there was a big push from the private sector to do worker betterment programs.

So you have your on-the-job training, especially in these massive factories, and that’s fine. But there’s a missing piece in terms of these social elements. So particularly for female workers, how you teach them skills that maybe they wouldn’t have been taught in school.

So financial literacy, communications programs, family planning and health. So these sorts of things, we would go in and we would develop programs that had a train-the-trainer sort of model for folks who know what that is. So one person would teach another, would teach another.

So more of an exponential approach to education that really, and we’ll get into this, like you mentioned, during my theories of change. But these sort of things that are able to impact massive amounts of workers at scale that are such fulfilling programs that serve a business purpose, of course, but also serve a very much an altruistic purpose. Interesting.

And this is pre-sustainable development goals, like before UNDP had actually launched the SDGs. So it would have been 20, between 2013 and 17. So right about that time.

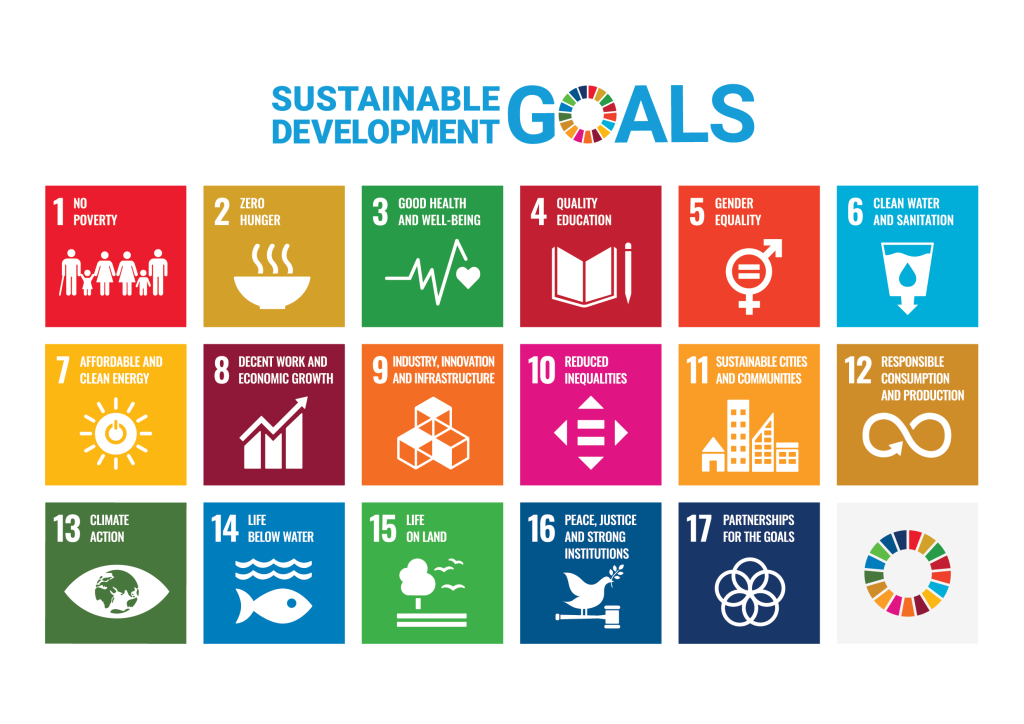

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Saurabh: So that was a transition where you were in China. That’s right. So did you see any impact after SDGs in the way you’re strategizing, in the way you’re implementing your models of sustainability? Did you find any changes in that? Did you switch or how was it?

John: Yeah, certainly when it comes to things like reporting and communications, a lot of businesses and not a lot, the majority, the vast majority of businesses, particularly today, now align how they communicate with the SDGs.That is a requirement from reporting bodies, for sure. But it’s also just a very helpful methodology in how to communicate that gets us all sort of trying to use the same language. So I think the SDGs have done an amazing job with that far better than the Millennium Development Goals.

But the SDGs have done a really good job when it comes to helping us communicate better. Okay. Okay.

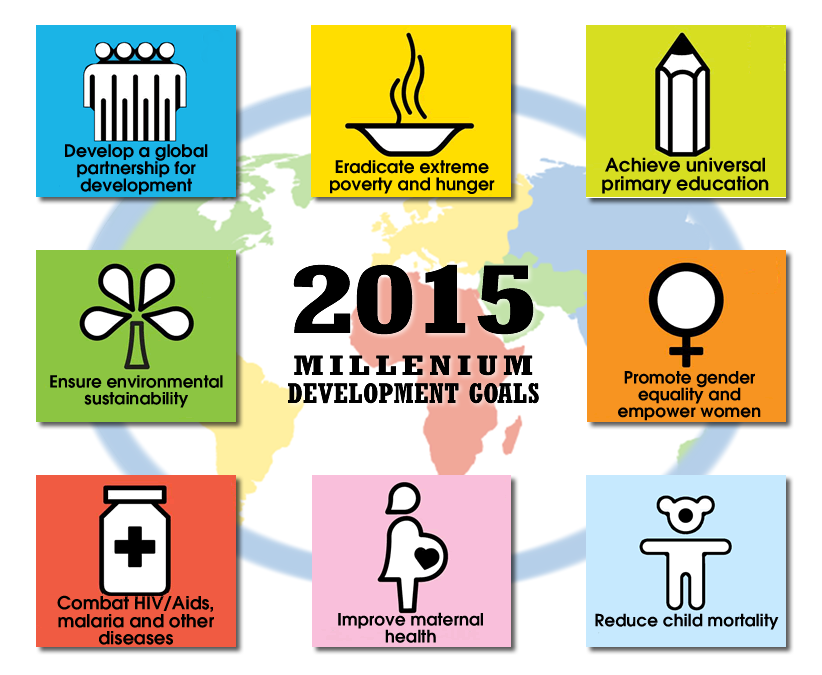

Saurabh: In terms of MDGs, since you were working on Millennium Development Goals, and then you went to SDGs and that time you were in China. Is there any difference that you saw? Because SDGs are more wholesome and they wrap around many, many sustainable goals and they look into sustainability application of multiple factors of life in the society and business. So did you see any major switch? Absolutely.

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals

John: So I think with the Millennium Development Goals, I’m not going to say they were a failure because that’s wrong, because they were not a failure, but I think they could have been improved had there been larger stakeholder input and collaboration when it came to developing the MDGs. And that was rectified with the SDGs, where there was a lot of stakeholder engagement to come up with what these SDGs were going to be. And I think because of that, there was a lot more excitement around the possibilities for the SDGs, not just from the public sector and the UN bodies, but just business in general. because A, it made a lot more sense, it was a lot more practicable, and it was a lot more relatable to their businesses.

Whereas the MDGs were just, they were highly altruistic, but they didn’t really relate to business and the SDGs are very business-focused, so a lot more excitement. And I think that’s why we’ve seen a lot more movement on the SDGs than the MDGs. Lots of acronyms for non-UN people.

Saurabh: Okay, coming to the United Nations, you have worked with the United Nations and you must be having a lot of insights and experience. I would like to understand more from people, like audience point of view, that there are a lot of our audience who, you know, young people who aspire to work with the United Nations at some point of time. So what skills and experiences were necessary for you and what’s the advice for the audience? Patience? Does that count as a skill? Because it definitely takes patience to work within the UN system, not just the UN itself, but any of the bodies of the UN.

John: So I think it’s really important to go in to the UN with an open mind if one wants to work there. I went there and I remember one of my master’s degrees, I have two, one of them is in the study of the United Nations specifically. And when I started work there, I had these ideas about what the organization was.

I thought I would go in and it would be super high tech, sort of like working at the CIA, and it’s not. We were working on old, you know, desktop computers from 1995. Like it’s just another, it’s sort of another job in a lot of ways, right? So getting your head around that was quite interesting.

But I think the biggest skill and probably the thing that may surprise people the most is that the UN highly values generalists versus specialists. I thought it would be the other way around. And this is not to say that there are not specialists.

Of course, there are. You know, if you’re in nuclear disarmament, you have to have a specialization in that. But for the most part, the people that are the, let’s call them the civil servants of the UN system are generalists.

John as an Emcee at the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative APAC Roundtable, 2019

I am a trained generalist, so I’m able to take a lot of information, synthesize it quickly and present it out. I don’t have a, at least at that time, I didn’t have a specialty per se. And this is, I can demonstrate this pretty easily by showing you a couple of the roles that I had at the UN.

So I started off in editorial. Then I moved into post-conflict peace building, decolonization, nuclear disarmament, and I ended in counterterrorism. I don’t know anything about any of those special subjects, but I was able to synthesize that information.

And this is how a lot of people work there. So the biggest thing to remember if somebody wants to work for the organization is to be able to have that generalist mindset to truly be successful. And the reason that is that way is because the UN, they like to move people around.

So very rarely will you see somebody in a role for more than about a year and a half. They prize moving people around. And if that’s the case, if that’s how the organizations work, you can’t have a specialization.

Saurabh: Yeah, that’s also true. Yeah, that’s a very good point. And how, if somebody wants to enter into United Nations, the entire hood and the entire network of work that they do, and they have a lot of work that is as consultation and on the job as well.

So what is their advice? Like, how should they go about what skills like skills? I think some of the skills you’ve shared is more about when they get inside, how do they progress or what do they do? But how do they get inside any ideas about that for the audience? Yeah, absolutely. So there are and there are a number of different websites for the different organizational bodies that have job listings. Right.

And I think there’s even I haven’t looked in a while, but I think there are even a few that consolidate all the job listings, which is very useful. It’s about finding the job that you do have that skill in. Maybe it’s something that you studied in school or something that you’ve been consulting on.

You have a client base that you’ve developed expertise in and then finding roles within that. Are there always going to be like for like applicable jobs at the UN? Probably not. So I think in some instances, it takes a little bit of creative thinking to look at a job posting from the UN and say, okay, that’s very bureaucratic language.

How does that relate to all of this experience that I have? Because it may not be so obvious on the surface. It’s not as easy as just popping onto LinkedIn and then seeing a job and going through the qualifications. It’s not going to match because they’re totally different sectors.

So thinking about it creatively, and I would definitely advise against people just spamming out their CV onto the UN site. It’s very easy to think that’s the right way because there’s hundreds of jobs at any one time. But the application process is long.

It takes a lot of forms and cells to click into on a website. So definitely don’t do that approach. Find the job that has your particular skill set and go for that.

And be patient, as I said before, because you’re up against thousands of other people at any one time. It’s not like looking for a normal job. Yeah, exactly.

Saurabh: That’s very interesting. Good to know. Thank you so much, John.This is very useful. Now coming to the sustainable business practices and case studies. Could you share an example of a company that nails sustainable practices and what it means for the business environment?

John: I will preface this all by saying there’s no such thing as a perfect company. So it does not exist, right? So when I talk about companies that are doing good, it’s in a very particular area. This does not mean that the whole company is good because that doesn’t exist. There’s always a bad something somewhere in a company.

The example I like to give, which particularly for people in North America is going to maybe get them thinking I’m very strange. But Walmart actually does quite a good job in many ways when it comes to good things for their workers in their supply chain. So when I was talking about working in China, a bit of that work was done developing worker programs with the Walmart Foundation.

And so these programs are helping out workers across their 60 plus factories in China. And we’re talking on the order of I think at the end of the three-year program, half a million women had gone through this program. So massive amounts of participation through this and upskilling that’s gone into that as well.

As a part of his work with sustainability in China, John Pabon spoke at the WalMart Women in Factories Program Annual Conference, in 2016

Now is Walmart a good company when it comes to workers’ rights in the United States? No, they’re terrible. So this is what I’m saying is there’s no such thing as a perfect company. But I think that’s a really good example of a company doing good things.

And the reason why it’s a good example is because it shows a really nice marriage of the altruistic do-good-for-people-or-the-planet side of things with the business need. Because when we go into talking to businesses as a consultant, I can’t go into senior executives and say, hey, let’s save the world. They’ll laugh at me and they’ll kick me out.

So I need to approach them with their language. And what we did when we introduced that program was we said, okay, if we go in and we upskill your workers and we make sure they are happier, they’re healthier, they’re showing up to work more, there’s lower absenteeism, higher productivity, and all of a sudden, more money for the factory. You’ve done a good thing for the people, but you’ve done a good thing for the factory.

Sustainability with Walmart in China

And yes, a lot of people may hear that and say, oh, that’s really gross. But that’s the reality of where we are, unfortunately. You have to talk in their language.

And we may find it unpalatable, but this is what we have to do if we want these companies to change. Also, this is one of the agenda behind sustainable development goals is to have stakeholders interested as per their functions and create a world that is more like shared, like values are shared. So yes, I think that’s good.

Saurabh: I have a curiosity here that how did you pull out such a big number? Because half a million is a very large number, especially coming to something related to sustainability. It’s not about sales. It’s something with very important costs.

John: So when I was talking earlier about the train the trainer model, where it’s more of an exponential model. So we made sure to track over the course of those three years how many people directly went through the program. That’s a very easy number to track.

And then we track sort of the second tier. So how many people they communicated that information to. The half million was the third tier, right? So it’s more of an extrapolation.

But I think it’s a very strong scientifically bound extrapolation that’s getting us to a reasonable estimate of how many people have gone through. And that was many years ago. So I can’t imagine how many have been impacted by this program now.

Saurabh:And did they use any kind of systems like management software or something to run the entire program? Was there any kind of dashboard or any technology used?

John: Absolutely. So it’s interesting.It was one of the first programs that incorporated the use of mobile app technology into any of the social space. Because this would have been back in, I want to say, 2013, 2014-ish. So still early days.

And especially in a developing country, most people didn’t have mobile phones. So a lot of people would even share a phone, for example. And so it was one of the first instances of that.

Speaking at the World Supply Chain Forum, 2018

And then as a result of this program, we also partnered with one of the major Chinese universities to develop a scientific framework to model this in a way that could be replicated to different businesses and different sort of environments. Because that hadn’t existed either. So a lot of big learnings and moving the needle forward through this one singular program.

And the software was developed particularly for this program or that already existed? It was developed specifically for this program. And I think there are other companies that have then used that. Because if I remember correctly, again, this is a while ago, I think it was an open source.So it was used in the spirit of partnership.

Saurabh: What are the different hurdles, can you share, based on your experience, that companies come across while doing the sustainability practices? What are the roadblocks they generally face in the early stages?

John: Yeah, the biggest one. And this is a hurdle that if you can get across it, it will spell happy days for your sustainability initiatives.And that’s having a champion at the top of your organization. It doesn’t matter if it’s a private sector company, the C-suite, an NGO, it’s an executive or a benefactor, whoever it might be, there has to be somebody at the top. Particularly somebody that has access to the money.

Because that can spell make or break for these initiatives. And a lot of times when people think of sustainability initiatives, they think bottom-up approach. So have employees create a committee and start talking about it.

And that’s fine. But again, without that support from the top, it tends to be very short-lived. That’s not just me saying that, that’s just based on many years of experience.

So the biggest thing is for organizations to have somebody at the top. And the second important thing is to really understand what it is you’re trying to accomplish. Because a lot of times with these programs, they try to do too much.

And when you try to do everything, you don’t do much at all. So be very specific in terms of what you’re trying to accomplish, what your goals are, and your KPIs, and what success actually looks like. And this doesn’t matter.

You could even work for an NGO where that sort of language doesn’t really come into conversations much. But you need to kind of think that way to what does success look like and how do you measure that success. These are two very important factors.

Because then not only does that keep the program going, but if you can see success based on what you determine success would be, that’s going to put some wind in your sails to keep you going and keep you energized and activated to make the program even stronger. So this is a challenge.

Saurabh: So top-down is like you would have to find some champion in the organization who believes in the cause or who believes in this entire model.So let’s say that when you go to an organization, since you’re a consulting firm also, when you go to an organization, how do you find who’s the right champion? Do you have to talk to a lot of people in the organization or do you study, research the website? How do you go about that?

John: So it’s different in every engagement typically, but normally it tends to be either if we’re talking private sector, it’s the CFO. So the chief financial officer or the chief operations officer, the COO. It’s usually those two.And if you can get one of those two people or hopefully both. And why? So the CFO, because they hold the money. And so if they’re getting in the way, so it’s not even if they’re not a champion.

Even worse is, and we see this sometimes, is there’ll be somebody at the top that purposely gets in the way. And they said, no, I’m not supporting this at all. And that’s terrible.

But if you get the person with the money on board, then money tends to flow a little easier and you don’t have to fight as hard. And the operations officer, because they ultimately impact the strategic direction of a business. So if you have them on board, one, two, or both, then things are a lot easier.

This is not to say that if you don’t have them, you can’t do anything. Because of course you can. It’s just going to be a lot more difficult to be doing things long term and at scale.

Saurabh: But why not the CSR people? People generally think that we should first get to the CSR head or CSR board or let’s say the HR people.

John: So it depends on kind of what the initiative is as well. So for example, when I use that Walmart example, we didn’t approach a C-level person. We approached the people that were more, I suppose, HR-related folks.

Because they were worried about absenteeism and turnover and these sorts of issues that we were trying to address through how we pitched this program. And it’s the same thing. So if your initiative is around health and wellness, you probably want to approach an HR person.

If it is around, let’s say, reporting or communications, you would approach the CMO, the marketing person. If it is related to strategic and operational parts of a business, approach the CFO. So all of this to say that when you develop these programs, it’s not as easy as just going in and pitching.

There is, like you referenced, a lot of research that needs to go into this to be approaching the right stakeholders. Or else you’re going to have doors slammed in your face, which happens a lot. I’m sure.You want to avoid it as much as possible.

Saurabh: That was very useful. So coming to theory of change and effective communication. So you have crafted a very unique approach towards sustainable communication over these years.So I’d like to know a bit more about your theory of change and how do you think that applies to the business world?

John: So I call myself a pragmatic altruist. So altruist meaning I care, I want to save the planet and people or else I wouldn’t do this work, of course. But pragmatic because I operate very squarely in the realm of what’s realistic and what’s possible.

So a lot of times folks in our space, they tend to veer more into the altruistic and the do good and having rose-colored glasses on versus the practical, what’s actually realistic. And I think mixing the two, a healthy balance of the two has worked very well for me. And certainly the folks that I surround myself with and the businesses that I work with.

And I think mixing the two, a healthy balance of the two has worked very well for me. And certainly the folks that I surround myself with and the businesses that I work with.

So balancing those two things out in every approach that I use, whether it’s communications or engaging with clients or whatever it might be, has worked out quite well. Now, when it comes to communications, I think generally speaking over the past 40 plus years, we’ve been pretty bad at communications in the world of sustainability. I think that the messaging and the marketing has not been amazing.

We could certainly do a better job. And I think about the messages that the majority of the population gets, right? You see these advertisements of the polar bear on the melting ice cap or the starving child in some far off country and all these sorts of doom and gloom scenarios that if you’re sitting watching television at home, you sort of throw your hands back and go, what am I supposed to do? There’s very rarely a, this is what you can do about it that’s practicable and relatable to your life. So this is how I approach when I do communications is how can people actually take this information and do something with it? Whether that is showing them what the first step is, because that’s usually a sticking point.

People just don’t know where to start. Or how do you make it something that is relatable to their lives? I always tell people to find their passion point and to pursue that and that they don’t have to do everything in the world of sustainability to be a quote unquote good person or a sustainable person, right? If you don’t want to be a vegan, that’s okay. You don’t have to be a vegan.

You can do other things that will help to promote a better future. So it’s about making the work that we do and the things that we’re asking people to sacrifice for a better future more palatable to them as much as possible versus being too extreme in one direction or the other.

Saurabh: So how do you apply your theory of change to a business? When you talk to businesses, when you talk to companies, how do you communicate to them about your theory of change?

John: The biggest thing that happens when I approach a company, certainly as a first instance, if I’ve never talked to them before, they’re very much the same as people.They care. They want to do everything. So they’ll say, okay, we have this laundry list of things that we want to get done.

How do we do it? And I tell them every single time, well, we need to figure out what’s most important because, yeah, you might have 100 things you want to get done, but they’re not all built equally. Some are far more important than others. Some are things you can achieve easily.

Some are things that they might sound like they matter, but maybe for the short term aren’t as important. So how do we call that list down? And we go through a process called materiality, which I won’t bore listeners with because it is very boring, to figure out what is most important for that particular company or business. And that’s usually a very good starting point to help them understand, okay, we don’t need to do everything.

We can focus on these two or three issues and really do them very, very well instead of trying to do 50 issues and only partially do them. And I think that is good not just for the business world, but it’s good for us as individuals as well because as people who care, the second I step outside, I want to adopt every dog, feed every homeless person, and then go build a house on the weekends. And I can’t do that, right? We’re only one person.

So find the thing that you care about that resonates with you, that you have a special skill in perhaps, or if you’re financially well off, congratulations, that you can contribute to financially because these things need money to keep going. And focus on that knowing that there are billions of other people that care just as much as you. You don’t have to be an army of one.

Onboard the world’s most sustainable cruise ship, the Costa Venezia in 2019

And then focus on that. And certainly in my own experience in the way I’ve approached my work, I’ve had to really embrace that and put blinders on to a lot of all the things going on around me because do I want to do everything? Yeah, of course I do. Can I do everything? No, of course I can’t.

And that takes a very, very long time to psychologically get over because what’s going to happen is when people start to use this approach, other people will come in and say, oh, why aren’t you doing this? Or why aren’t you doing that? Or oh, you’re bad because you fly or you aren’t a vegan so you’re a bad person. All these messages that for everybody listening wants you to remember there is no such thing as a perfect environmentalist and you don’t have to do every single thing. Pick that lane that you want to contribute to and focus on that.

Saurabh: Right. So in terms of your theory of change, what we understand is focus is very, very important and you have to be pragmatic in your approach, right?

John: Absolutely. And that’s in everything, including in how you approach.We talked about it through the business lens, but even how you approach others. So how I talk to people that are on the fence about doing anything or don’t know where to start, I can’t approach them as an aggravated person or as an angry activist, right? It’s going to turn them off. There’s an interesting story.

I was speaking on a panel, I’m not going to say where, because people will then look it up, but I was on a panel at a book fair about a year ago and I was sitting next to somebody that had a very diametrically opposed position on how to build a sustainable future. They took a more activist approach and I took, as I’ve talked about, a more pragmatic approach. And he was very angry, rightly so.

We’re all angry, right? We want more progress. We get that. It’s how you bottle that anger and act on it.

But he was essentially yelling at the crowd and yelling at them and being angry with them. And this is a group of people who have devoted an hour of their lives to listen to us, so they’re already the converted. And I paused and I asked people, I said, please, can you raise your hand if you’re a vegetarian? A few people raised their hand.

Vegans, fewer. How many people would give up international travel? No hands. How many people would give up your cell phone? No hands.

Go live off the grid. All of these extreme things, nobody raised their hand. And I said, well, if this is the 1% that already care and they’re not going to do these things, what hope do we have of the other 99% doing these things that aren’t converted yet? So we need to approach things in a very realistic, pragmatic manner, not to go off into extremes or else we’re going to lose our audience.

Saurabh: Coming to critical perspectives on greenwashing, this is where we would like to understand a bit more that how do you see the role of governments and policies in fighting greenwashing based on your work?

John: So greenwashing is an interesting topic. But when it comes to greenwashing, I think we need to remember there’s three big stakeholders and this is sustainability in general. So you have individuals and people power and the things that we can do. You have government and the things government’s supposed to be doing.

And then you have the private sector and the things that they do. When it comes to greenwashing, obviously this is coming primarily from corporations. And so because of that, the corporations are not going to self-govern themselves.

They tend not to do that, especially if they’re going to be as bad as to greenwash. So that’s where government regulation needs to come into play. Unfortunately, with the exception of the EU and Australia, those are the only two places in the world that are genuinely enforcing some sort of greenwashing legislation at this point in time.

So hopefully more governments do start to take note and put economic pressures or some economic lever or other policy lever to stop greenwashing because it’s a disservice to the companies that are doing the right thing. But also, of course, it’s false advertising to consumers.

Saurabh: So any other parts of that you spoke about Australia and any other parts of the world that you see that there’s a shift happening from the policy level towards greenwashing?

John: No, unfortunately it’s Australia and the EU and that is it at this moment in time. And that’s pretty spot on with how things are going on in sustainability writ large. The Climate Action Tracker is a great resource that has been tracking how individual governments are doing versus their Paris climate agreements.

And the Paris climate agreements are coming up, I think, this year or next year. There are exactly zero countries on track to meet their Paris climate targets. So to think that policymakers are then going to be going into the niche area of regulating greenwashing is a pretty big ask.

There are exactly zero countries on track to meet their Paris climate targets. So to think that policymakers are then going to be going into the niche area of regulating greenwashing is a pretty big ask.

So the fact that EU and Australia are doing anything at all, I’m not going to say I’m happy about, but I’m surprised they are.

Saurabh: From experience, what are the common greenwashing practices to watch out for the common people, like for consumers and stakeholders?

John: Absolutely. So there’s a few big ways that greenwashing shows itself. And if anybody’s going to research greenwashing or Google greenwashing, you’re going to find lots of articles that say the 10 commandments of greenwashing or the 20 ways of greenwashing, all these sort of big numbers.

It’s three ways. That’s it. So number one is in marketing.

It’s greenspeak. It’s how things are positioned. So the back of a pack, are they using really fluffy language? Are they using too many statistics that seem a little fishy? Are they doing comparisons of things without giving you a proper understanding of what they’re comparing? So this sort of stuff that you look at and you go, what? There’s also the use of semiotics, which is just a fancy word for how colors and symbols denote meaning.

And when I say that, I’m thinking the green box or the advertising with flowers on it. There’s a famous ad and I don’t remember what company it was. It was a car company that had a daisy in the exhaust pipe.

We see this and we say that’s ridiculous, but the idea is to denote that this is a sustainable car. So it’s these sort of things that happen in the marketing. The second is misdirection.

So they want you to focus on one particular area and not look at everything else happening holistically within a business. That’s a thing that individual consumers will likely experience, but this is more at a larger policy level is green scamming organizations. So there are highly cashed up organizations, usually the worst of the worst companies that will fund lobbying groups that on the surface look like they’re doing good for the planet, but in reality, they’re really bad.

Consumers don’t really have to worry about that stuff. That’s more for politicians. But overall, when you go to the store and when you’re trying to make a purchase decision, I absolutely recommend that people kind of trust their gut because greenwashing by and large is not very slick marketing.

It’s pretty obvious and it’s really bad. Like very rarely you see an example of greenwashing where you’re like, oh, I didn’t know that was greenwashing. It’s most of the time pretty obvious.

So if something sounds too good to be true, trust your gut and look for another product. Sure. Sure.

Saurabh: That’s interesting. That simplifies the entire because people are confused about and what, because the list keeps growing. So having a broad category does help us as an audience.Coming to the book, your book, you have written the book, The Great Greenwashing, a lot of interesting case studies, a lot of interesting examples and analogy. So can you share any such stories from the book where greenwashing was exposed and addressed and how do we prevent such kind of practices from you?

John: Absolutely. There are a few cases that have been coming to light in sort of the past few years of really egregious greenwashing that’s been happening over the long term.

The biggest one that certainly made the news in most places around the world is from ExxonMobil, who have really been working for the past 60-ish years to not outwardly greenwash, because I think for most people, you think of an oil and gas company, you know they can’t be sustainable, but to work against the science and to push through fake science around what damage the oil and gas industry is doing to the planet and also to spend money lobbying politicians to pass rules that would benefit the business, not benefit the planet or people. So this has now come to light. There’s also smaller examples that I think today people are kind of waking up to.

I was going to say my favorite example, but it’s obviously not my favorite because it’s greenwashing, is this idea that when you go to a hotel, you’re asked to hang up your towel to save water. That’s one of the original examples of greenwashing because yes, while it may save a bit of water and help the planet from that perspective, the original aim of that was to save the hotel water because that bill is extremely expensive for them on their budget lines. So it’s a bit of greenwashing that’s been now embedded and baked into how we approach things.

And I’m not saying this to tell people to stop hanging up your towels, hang up your towels, but don’t do that and then think, oh, I’ve saved the planet because you’ve just saved the bottom line of that particular hotel. So there are these sorts of examples that are coming out now. And I think as well, a lot of the more, let’s call them silly things that companies try to do to try to pull a fast one over on consumers.

John at the Release of his new book, the Great Greenwashing

I mentioned the green box. One of my favorite examples was from my time living in China. There was across the street from where I lived, they were building this massive tower mall, sky rise sort of thing.

And building is highly polluting and it kicks up dust and it’s not great. But out in the front, they had this wall up that had these pastoral images of cows and fields and really pretty green scenes that is supposed to sort of show people that this is a clean and green thing going on when obviously I can see, everybody could see that it’s not. So that goes back to this idea of looking at something and trusting your gut and realizing, oh, that’s not really what’s going on here.

Saurabh: In terms of for any kind of ideas for consumer, I know that you already shared some of the broad examples, but how can customers support genuine sustainability efforts and rather than supporting greenwashing based businesses?

John: People are not going to like my answer. So unfortunately, it does take research.And I say that, and I know people are thinking, oh my gosh, I don’t want to do research. And I understand. I don’t want to do research when I go to the store either.

I don’t want to have to pull out my phone to Google what a product or company is every time I want to make a choice. But unfortunately, that’s the reality of where we are today. So there are some companies, of course, and industries that I think people can look at and say, okay, I know that that can’t be sustainable and understand that, and that’s fine.

But there are others where you’ll have to research. When you go to the store, particularly when you go to the grocery store, there are a few certification labels that if you see them on a package, that will help you know that that is a good certified, good for the planet brand. A few of those are the Rainforest Alliance.

So that’s usually when you’re buying coffee or tea, the package will have a little tree frog on it. That is a good stamp of approval saying that is a sustainable company. So if you see that, you know that’s a good company.

I always mess up this name because it’s a tongue twister, the Forest Stewardship Council, FSC, which is for wood products. So if you go to an Ikea, for example, a lot of their products will be certified with the FSC logo, and that’s a good one as well. And then one of the most popular currently is the B Corp certification.

Reputed Sustainability Certifications, to Avoid Greenwashing

So a lot of businesses, not just in the grocery store, but textile businesses, home goods, all these businesses will have a big B and a circle. It’s in black and white. And that is another stamp of approval of an organization that has gone through a very rigorous process to be certified as a good-for-the-planet company.

So these are three really good stamps of approval that if you see them on a business, you’ll know that you’re supporting the right thing. John, but these are mostly in Europe, and we see them in European countries or maybe in Australia, since you’re in Australia, or in US. But there are so many countries in Asia where you don’t see these.

Saurabh: So how do consumers in these countries, or even India, it’s like such a big population, big consumer base, how do they find, how do they decide? Any generic advice for them?

John: Yeah. So it’s interesting. The tree frog logo, the rainforest. Yeah, that is coming up. That’s a global, almost a global one. So you’re likely to see that.

Saurabh: B Corp, we don’t have. No. And most markets don’t, you’re right.

John: So B Corp is a little rare outside of some of those more Western markets. So with the exception of that one tree frog logo, I think certainly looking at the brand as a whole, and that’s where this research part comes into it. There are some brands that we know, like Ikea, again, as an example, is a highly sustainable brand.

They have that as part of their ethos. So when you go into an Ikea, you’ll know that it’s an okay decision to shop there. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than going somewhere else.

Unfortunately, in a lot of developing markets, these things through government regulation and through even businesses developing their own sort of seals of approval, this is the stuff that needs to happen. And it’s not quite where things are at yet. So we still need to be pulling a lot of these government levers, particularly in the developing world to make sure this is happening.

I think about my time in China, and with the exception of the multinational companies that have kind of been forced to adopt these stamps of approval or ways of working, if they were left to their own devices, they probably wouldn’t have done it. Great. In terms of when you go to companies, or when we talk about companies, and you approach them for the right kind of sustainability strategies that are not greenwashed, at the same time, they also have to make profit, long term profits.

Saurabh: But let’s talk more from competitive advantage point of view. So how do they use sustainability as a competitive advantage without greenwashing and without affecting their KPIs? So any thoughts on that? Because this is a very, very, very, very tricky subject. And this is where a lot of businesses struggle in being truly sustainable.

John: It’s true. And the push for sustainability, particularly in the private sector, is something that is a competitive advantage if used the right way. It could be an absolute disservice to your business if you do it the wrong way, especially when it comes to government regulation.

But for those companies that have now really evolved along their sustainability journey, I’m talking the big companies that have been doing this for decades, we know that they outcompete their competition, their peers. Because not only is it a thing that is good for the planet, I think that’s the afterthought. But if you have your business truly operating sustainably, that’s going to positively impact your operations, your logistics.

It’s going to make your people happier and probably lower turnover and absenteeism. It’s just going to make your business operate better at large. So yeah, you’re doing a great thing for the planet and people, but the businesses that are genuinely sustainable are also sustainable businesses.

So yeah, you’re doing a great thing for the planet and people, but the businesses that are genuinely sustainable are also sustainable businesses.

I’m talking sustainable from they’re going to be here for the long run. We’re in this transition period today where I think particularly when it comes to consumer goods, companies that are really far behind, they haven’t even started their sustainability journey yet, or even worse, they refuse to develop a sustainability program or initiative, they’re not going to be around much longer. I just don’t see room in the market for them because consumers are certainly in a lot of parts of the world asking for better for the planet products to varying degrees.

And it’s questionable if they’ll pay for them, but that’s a different subject. But they’re demanding this and companies now, the ones doing the right thing have entered this virtuous cycle where they’re competing with one another on who can be the best company, the genuinely best company, because they don’t want to greenwash. They don’t want to do the wrong thing because they understand the negative impact of that on their business.

So these things are already happening. And I think that it will continue to happen where the, use an overused adage, the triple bottom line looking at people, profit, and planet is now so integrated into businesses that there is no uncoupling of them. So for most businesses, sustainability is no longer just sitting in a single department.

Sustainability is now filtered out throughout the entire organizations. There is no way to unwrap all of that. It is just the way business is done now.

Saurabh: Yeah, great. John, since you’ve worked in different markets, we also would like to understand from your experience that when it comes to reaching out to a CSR team or corporate sustainability team, whatever the team is called in, because in different sectors, it’s named differently. So what kind of stakeholders you come across? Like what is this team or board made up like? I think earlier you spoke about talking to CEOs, chief operating officers and CFOs, but generally I’m sure these are not the only two people you’re talking to.

John: So when you have to make a business case for sustainability for a company, which is B2B, what kind of team that you have to deal with, what kind of preparations you have to do? Typically, it’ll end up being in one of a few different types of configurations. So it will either be sitting within a communications or PR department. Those tend to be some of the stakeholders that we work with quite a bit.

And not just because I work in marketing and communication sides of things, but just in general, sustainability will often get passed over to the communications folks. I don’t know how that happened. There’s also those that are involved in public affairs.

Which market are you talking about right now, Australia, EU or globally? Globally, it tends to be that way. And typically when a business is just starting out on their sustainability journey in any market, it will get pushed over to the communications people. Again, I don’t know how that’s become a thing, but that’s usually where sustainability starts.

There’s also, especially in highly regulated industries or markets, sometimes sustainability will sit within the public affairs function, the government affairs function. And that makes sense because it has such a deep link with policy and regulations. So that’s particularly in China, India as well, which is a highly regulated when it comes to CSR.

So it will usually sit within a public policy type of a function within the organization. Beyond that, a lot of organizations also have bottom up sustainability committees, ad hoc committees, groups that are putting together initiatives. So those tend to be more just volunteers.

And because of that, it could be anybody in an organization that is usually no rhyme or reason as to who those stakeholders are. If I’m looking at markets like developing markets, especially with supply chain work that I’ve done. So being in and out of factories, it tends to be a lot of talking with middle managers who are very difficult to talk to you about these things because they have very little control over, like we talked about earlier, finance and strategy.

But they have so many KPIs of what they have to deliver that getting them to think a little more laterally about how to approach things, even if it is to their benefit, is to them, it seems sort of a waste of time. So those are the C-level, which we usually don’t start conversations with. We end up getting there, but they are, like I mentioned earlier, they have to be part of the conversation at some point.

But the markets are all generally the same. So it doesn’t matter developing, developed, Western or not. The way sustainability has manifested itself always tends to be the same.

And it’s very industry agnostic as well, especially when it comes to solutions and approaches, which as a practitioner, that makes my life a little bit easier because I know what to expect. And so that’s interesting. But when it comes to the thinking around sustainability, there are vast differences between the different markets in terms of how it is approached and then how we engage stakeholders in different conversations.

Saurabh: Right. These are very interesting ideas, John. We are getting to the root of sustainability and how it’s being, how somebody can, you know, how it’s being practiced at company level.

So we’re getting to the nuts and bolts of the functions of sustainability at a corporate level. Great insights. One of the last questions I have for you is from the audience side, because a lot of our audience, as I mentioned earlier, is college students or school students also who aspire to enter into sustainability or make the world a better place by the way they do things on day to day basis.

Also, we have a lot of people who are interested in listening to what you’re saying. They come from the background of they come from corporate background. So these are the people who are may not be in sustainability sector right now, but they are looking forward to entering the sustainability sector.

So can you share some of the thoughts, some some some tips that what should they study, what kind of books they should go for? What kind of courses they should do? Is there any actionable items other than just researching or, or, you know, developing the skills, some actionable things that they can do.

John: Besides my own books, right?

Saurabh: I mean, I always, I would advise everyone to, you know, have a copy of the book, go through, you will have a lot of insights from this book, especially what happens at the corporate level. Thanks.

John: So one of my, one of my roles, I chair a think tank group called the Asia Sustainability Leaders Council.And it’s a group of chief sustainability officers from mostly multinational companies from around APAC. And we met about a month, this should go a little over a month ago. And this one of the topics of conversation was around talent attraction.

It’s always around talent because the space moves so fast, right? And for these companies, what they’re finding and what they’re, you know, what they, they are wanting from, from potential future employees is not necessarily somebody that has a specialization in a particular area of sustainability. What they’re actually looking for is somebody who has a specialization in something else that they can then learn a bit about sustainability on the job. So it’s kind of counterintuitive to what maybe a lot of people think is going on.

A lot of people think I need to have a sustainability degree and I will apply that somehow in the private sector. It’s actually the opposite way, because I think there are enough. And I don’t want to scare anybody off from the degrees that they’re studying or the schooling that they’re doing or their passion points.

So don’t let me scare you. This is just, you know, a group of people’s opinion. It’s not the be all and end all, but because sustainability now is so filtered throughout all different parts of an organization and it doesn’t necessarily just sit in one particular team, there need to be applicable skills as well.

And the example that kept coming up for a lot of these companies was within research and development and supply chain and logistics. So those are specializations that if you have a degree in sustainability, you may not know what you’re doing when it comes to innovating a new product, right? Because that’s a very particular skillset or market research. But if you have a degree in market research or research and development and you go in and then maybe you’ll take a course from, I don’t know, from Cambridge or one of those other online courses that teaches you the foundations of sustainability, you can then start to apply that into your thinking.

But you have to have that foundational understanding of the work and the skillset before the sustainability, which is, again, a little bit different than how we used to approach things. And this honestly is where we wanted things to be when we started talking about this 15 years ago. This is where we wanted to be, so we made it.

But what I would encourage people to do is if, for example, you’re in an MBA course, a business administration course, consider how you embed sustainable thinking into the work that you’re doing or into your studies. So is it taking a side course somewhere? Is it in one of your projects that you do thinking through, okay, how do I embed sustainability? So start to have that in your thinking at all levels of education. But don’t feel like your hands are tied and you have to study something related to sustainability because that’s not necessarily true.

And even for folks who are in the corporate world now that want to transition into sustainability, they’re actually very well set to do so because they have all of that experience.

Saurabh: All they need now is a little bit of a buffering in terms of their knowledge and skill set and applied sustainability. Exactly right.

John: That’s a good word. That’s the word I was looking for. So the applied knowledge and expertise at this stage of the game is very favorably looked upon, especially if somebody’s trying to transition at some point in their career.

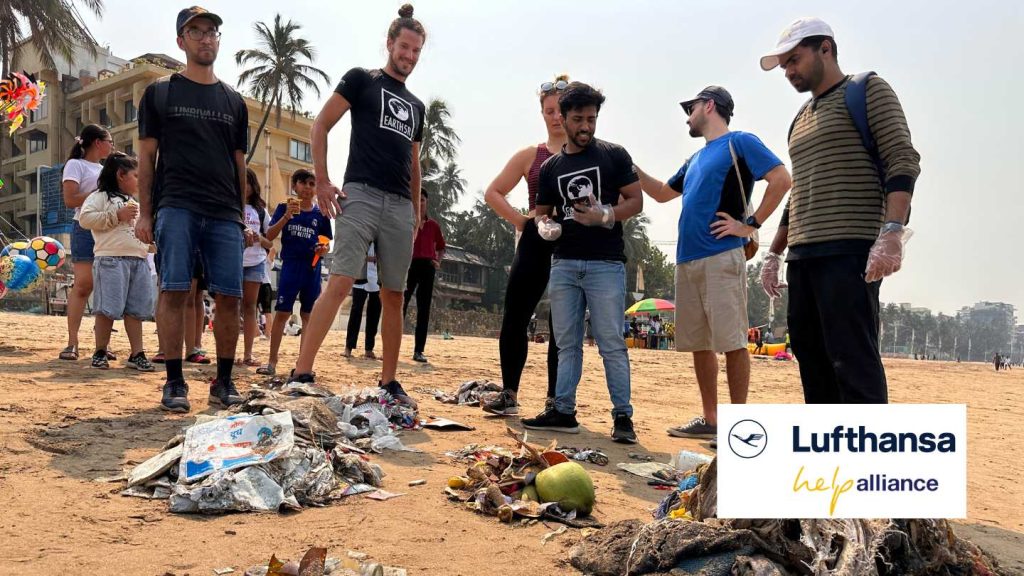

Saurabh: Which brings to the point that Earth 5R has, we have our own courses on our website, which are applied courses. So we have one foundation course into sustainability, which people can do in just six hours of time. But we have applied sustainability like sustainability in fashion, designing sustainability to food industry, sustainability for mechanical engineers.We have a lot of applied courses. So this is where people, it’s a very crash course kind of thing, but people learn. And we also have Earth 5R app, which people can use to practice.Once they have done these theory classes, they use this app, they go out, they do a bit of a field work, they study local ecosystem, they collect the data, they get work experience. So yes, as John, you’re rightly saying that applied knowledge is very, very important. Absolutely.

Earth5R’s Rivier Cleaning Project for the Mithi River in Mumbai, in collaboration with UNTIL

John: That’s amazing. And for anybody listening, we did not rehearse that. It was just seamless.

Saurabh: No, that’s exactly right. And these are the sort of things that the ways people can acquire these skills that they can then take and begin to apply.

John: Like I was talking about at the very beginning, a lot of my experience has been on the job experience, not necessarily from going through a particular course.

Saurabh: Yes. Great. John, thank you so much.Any parting words before we leave this conversation? We’ve covered so much. It’s been amazing. So thank you so much for the invitation.

John: Just a reiteration of a point I was making before, find your passion and just stick with that and know that you don’t have to do everything. And there’s no such thing as a perfect environmentalist. I think it’s really important because we see a lot of everything going on in the world right now, and we get a little bit despondent and we go, oh, what’s the point? But I think with more focus and really holding onto that passion point that we have, we’ll get further along without so many headaches and banging our heads against the wall.

Saurabh: Thank you, John. It was really great talking to you. We got a lot of information.

John: All the best. Cheers. Thanks so much.

– Reported by Ashi Parelkar

Earth5R is Earth5R is a UNESCO-recognized global environmental organization that is helping global communities and businesses transition towards a green economy. This is achieved through Earth5R’s Google award-winning app and state-of-the-art learning management system.

The Earth5R app acts as a catalyst for community-driven environmental action, enabling individuals to make a tangible impact.It addresses the issue of climate inaction by providing a platform for individuals to participate actively in environmental conservation and sustainability practices. By connecting users worldwide, the Earth5R app fosters a global community of environmental advocates.

Earth5R, alongside Lufthansa Group, spearheaded a successful beach cleanup in Mumbai.

Earth5R provides various opportunities for students and individuals to prepare them for the new age climate economy through hands-on courses which dive into essential topics such as urban sustainability, deforestation, circular economy, sustainable product design, life cycle assessments, green energy, and more.

Greenwashing is a pervasive issue that significantly impacts governance, growth, and the pursuit of genuine sustainability. In Earth5R’s Sustainable Futures podcast, Saurabh Gupta and John Pabon discuss how greenwashing has become a barrier to true environmental progress. Greenwashing misleads consumers by making false sustainability claims, ultimately hindering efforts to foster real change. Governance structures need to address greenwashing more effectively by creating stricter regulations to prevent greenwashing from misleading the public. Greenwashing not only confuses consumers but also damages the integrity of businesses that are genuinely committed to sustainability. Greenwashing thrives in a lack of transparency, and without proper governance, it will continue to undermine growth in the sustainability sector.

As discussed in the podcast, John Pabon emphasizes the need for strategies to identify and confront greenwashing, highlighting how this practice distorts sustainability goals. Greenwashing often leads to short-term profits for companies, but its long-term effect is damaging to both the environment and society. Growth in the sustainability industry must come from honest practices, not from the deceptive nature of greenwashing. Consumers must learn to recognize the signs of greenwashing to avoid being misled. By understanding greenwashing, consumers and businesses alike can take steps toward more responsible practices, free from the harms of greenwashing.

The discussion highlights that when greenwashing becomes too common, it stifles true growth and innovation. It is crucial for businesses to avoid greenwashing, as it can backfire and result in consumer distrust. Greenwashing dilutes the meaning of sustainability, making it harder for genuine sustainability efforts to gain traction. The fight against greenwashing is a fight for real environmental progress, and it requires collective action from consumers, businesses, and governments. As highlighted in the podcast, overcoming greenwashing will lead to more effective governance and more sustainable growth, ultimately benefiting everyone. In conclusion, the prevalence of greenwashing in today’s market underscores the importance of tackling it head-on to create a future where growth is defined by integrity and transparency, not by deceptive practices like greenwashing.