Earth5R Podcast: Cities

Our Sustainable Futures Podcast’s series premieres with a discussion focused on ‘The Cities of Tomorrow’. After a brief exploration of the key concept of cradle-to-cradle sustainability, Earth5R founder Saurabh Gupta and Corporate Sustainability and Civic Partnership Expert Ashwin Kak discuss the concerns arising with urban sustainability and the role of corporations in promoting innovation to tackle such concerns.

Next, the second half of the podcast delves into Expert Ashwin Kak’s anecdotal lessons on successes and failures within the sustainability field. This section focuses on his Zero Slum India Initiative, an ambitious manifesto about reducing slums in India. The discussion wraps up with some valuable insight into a career in corporate sustainability.

Chapters

- Welcome to the Sustainable Futures Podcast

- Introduction

- Concept: Cradle-to-Cradle Sustainability

- Problem of Urban Sustainability

- Innovation Economy and Public Policy

- Successes, Failures and Partnerships

- Zero Slum India

- Career Advice

Conversation:

Saurabh: Good evening, everyone. Welcome to the Sustainable Futures podcast. In today’s episode, the topic is “Cities of Tomorrow: Sustainable and Smart.” Our guest today is Mr. Ashwin Kak from Bangalore. Ashwin is a leading figure in sustainable development, influencing multiple sectors. So, Ashwin, welcome to today’s podcast. It’s good to have you here.

Ashwin: Thank you so much. My pleasure.

Saurabh: To tell you more about Ashwin, he has been a Sustainability Director at AB InBev Beverages in Bangalore and advises the Center of Excellence in Sustainable Development at the Goa Institute of Management and also worked at German Accelerator, where he mentors startups and startup founders in sustainability projects and CSR initiatives.

His past roles at AB InBev and Pidilite Industries have involved driving numerous sustainability initiatives, and he has been instrumental in advancing the sustainability agenda across the sector. So, I would like to welcome Ashwin. Ashwin, could you please introduce yourself and share a bit about your background?

Ashwin: Sure, I think you’ve summarized it well, but for the purpose of this podcast and its intended audience, I’ll take a step back and look at my career. I’ve been working for 14 years now, with nine of those years mostly in the space of sustainable development and CSR, or what I like to call corporate responsibility.

These are the roles I’ve held at Pidilite and now at AB InBev. The projects I’ve been part of range from education and skilling to women entrepreneurship development on the CSR side of things, and very specific sustainability activities and projects around climate action, agriculture, and water stewardship. It has been an interesting roller coaster ride. Partnerships have always been at the center of what we’ve tried to achieve in terms of impact across the different roles I’ve had. So yes, that’s been my journey.

Saurabh: It’s great to learn about your work, Ashwin. We are here to learn from you. Our audience includes many students, not just from India but from around the world, as well as sustainability experts, city administrators, and professional CSR practitioners. We’re here to learn from your vast experience.

One of the reasons we wanted you on our podcast was to gain insights from your corporate experience, especially your work on policy and systemic issues, which is very interesting. To begin with, Ashwin, can you share your journey in sustainability and CSR? How did you start, and where are you heading?

Ashwin: How I began is quite interesting. This was back in 2014-15, which coincidentally was also the time the SDGs were being launched. I was selling and marketing Fevicol across India, deeply entrenched in the commercial side of the business. But in 2015, I started wondering how I, as an individual, could create a larger impact while remaining in the corporate setup. It was an interesting time because Pidilite was setting up its CSR foundation team, and I became part of that team.

We started from scratch, with about five to ten people, and gradually built up the entire initiative. My transition from the commercial side of the business to the CSR side involved a lot of hands-on, on-the-job learning, and learning from experts in the field. Literally restarting my education and skilling journey, in general, if I could say that.

So, I took a lot of courses and certifications here and there, just learning micro-skills, if I could call them that, when it comes to sustainability in general. That’s how the transition for me really happened.

Ashwin led the creation of a self-sustaining water unit in Bengaluru and other cities during his time with AB InBev

Saurabh: Did you have any mentors since you were early in marketing and then transitioned to CSR? Did you have any mentors or senior support in that journey, or was it a self-starter experience?

Ashwin: I would say, to begin with, it was a lot of self-learning. But very soon, I realized the importance of having the right mentor. We ended up having a very nice team that I was working with. The people in the hierarchy who had dotted line reporting to me or were considered a level below in the corporate sense actually ended up being much better mentors for me in many ways.

Two or three of them, Mahendra Bhai and Ajit Bhai, were heading the foundations when we were setting up the foundation team. They had over two decades of experience at that time and were my first mentors in the larger development space.

After that, as you get into the domain, you don’t just interact internally but with many external partners. You go to industry events, get exposed to the ecosystem, and look for external potential guides and mentors. That pool really expanded for me. Today, I would say I have at least a dozen guides or mentors I often reach out to whenever I’m confused about something.

Saurabh: That’s very interesting. Typically, students coming from college think there is always a teacher or a boss who teaches you. But in the industry, things are very different, more complex, and can be more creative and innovative when it comes to mentoring and learning.

Ashwin: I think for any student, practitioner, or individual starting off in this space, the more they are humble and willing to learn and unlearn, the more it will help them. This is crucial in this profession or field.

I think for any student, practitioner, or individual starting off in this space, the more they are humble and willing to learn and unlearn, the more it will help them and consequently their cities.

Saurabh: It’s very good to know these insights from someone who has had a long career in sustainability at a very senior level. These are important learnings for everyone. Ashwin, can you explain the concept of cradle-to-cradle sustainability and how it applies to urban development? Cradle-to-cradle has recently become very popular. It started more as an architect-to-architect concept but is now entering the industry and systemic innovation. I’d like to know more about it since you’ve been working on it.

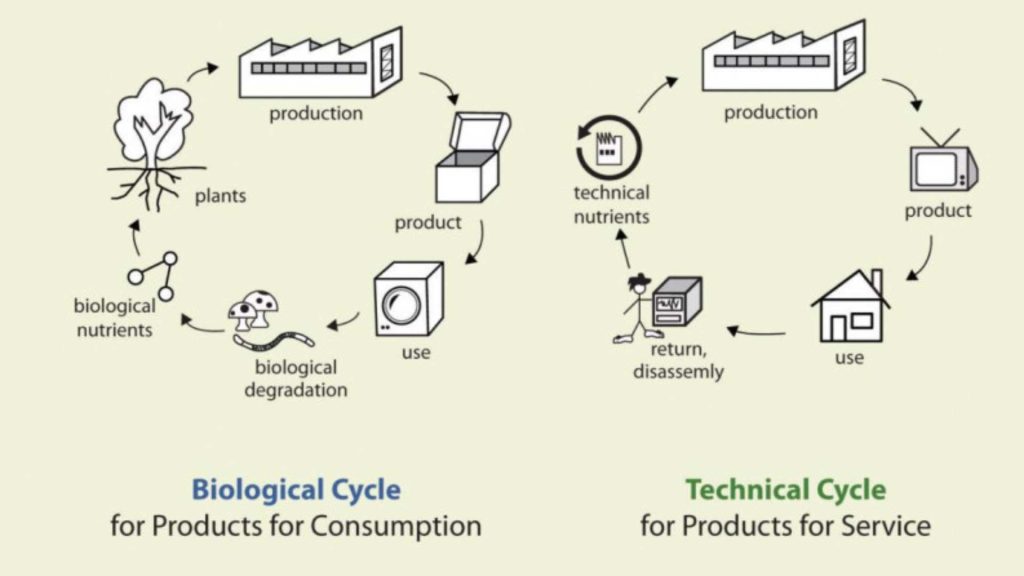

Ashwin: Yes, this is an interesting term. I got very interested in it around the time there was a lot of talk about the circular economy a few years back. The more I probed and looked for academic literature, practitioner perspectives, or research, the best text I found on this was a book literally called “Cradle to Cradle” by Michael Braungart and William McDonough. It’s a brilliant book. The authors have also written another great book called “Upcycle.”

When I was reading about it, it was an eye-opener in many ways. I’ll take a step back to explain what it is. When you think of a circular economy, or the pre-circular economy ideas of how businesses should run, you often consider the cradle-to-grave approach, right? That’s the traditional way of doing business, which includes everything from extracting raw materials to waste disposal.

Diagram Representation of Cradle-to-Cradle Sustainability in cities

For example, in the product industry, you have raw material extraction, processing, refining the intermediary steps, final product manufacturing, and transportation for both input materials and the finished product. Then you have product usage and disposal.

Now, what cradle-to-cradle does as a concept is view this process as a continuous loop that never stops. How does that happen? You start by examining the materials and components you use: can they be repurposed or recycled? You start looking at the product from a life cycle perspective.

For a company, this means you don’t view sustainability just as a product created and sold to the market, but also consider how this product will either return, get recycled, or get upcycled. This change in perspective can completely transform how you think about running a business.

I’ll give you a few examples. When we started having these brainstorming sessions within my team at AB InBev, we began to shift our focus from just recycling to upcycling. It’s a subtle but significant difference.

Saurabh: Very important, yes.

Ashwin Kak creating a Skilling Centre during his time at Pidilite at Sabarmati Jail in partnership with the Government of Gujrat

Ashwin: We began thinking about design as well because, in this context, design takes precedence. If your product cannot disintegrate into pieces that can be recycled, returned, or reused, then cradle-to-cradle doesn’t make sense.

Saurabh: Correct.

Ashwin: We became much better sustainability professionals by not thinking in a siloed way. We started asking the right questions of the new product development team, the design team, and the logistics or transportation team. It’s a comprehensive way of thinking.

The two great scientists and authors from Germany who developed this concept also have their own cradle-to-cradle certifications. But before getting into certifications, we need to change our mindset. That’s what cradle-to-cradle sustainability is about.

Ashwin, when he implemented a micro-entrepreneurship unit in Mahuva town of Bhavnagar District in Gujarat during his time leading the CSR activations at Pidilite

Saurabh: Do you have any examples of a particular item or process designed based on this principle that saw the light of day?

Ashwin: The best example is from when we re-evaluated our entire supply chain and realized that some elements of this concept were already in practice. For a beer company in India, most SKUs are sold in glass bottles, not cans. Cans are more common in Western countries or places like Vietnam. India is still very much a glass bottle market.

We realized the potential of glass bottles being recycled or returned six or eight times, or having a high recycled content. It was like discovering a gold mine. Previously, we viewed this from a strictly commercial or operational perspective: more returned bottles meant cost savings as fewer new bottles needed to be manufactured.

But from a carbon emissions perspective, every time a glass bottle is returned instead of creating a new one, you’re saving 80 to 95% on carbon emissions for that bottle.

Glass Beverage Bottles can be reused and refiled, significantly reducing the carbon footprint in cities

Saurabh: Right, right.

Ashwin: Because when you return a glass bottle, what do you have to do? You just have to wash it.

Saurabh: Correct.

Ashwin: There is nothing else. There is no manufacturing, processing, or refining. So that in itself becomes a very good cradle-to-cradle concept. I wouldn’t say it’s the perfect example because there is a lot that can be improved in the materials used, for example.

Saurabh: Right, right.

Ashwin: But for us, as a sustainability team, it became a crucial way to embed ourselves into what we call the reverse logistics system of our product mechanisms. Sometimes, the entire idea of sustainability and cradle-to-cradle models is already built into old systems, like glass bottles, which are one of the oldest packaging mechanisms.

Having a modern ideology in place helps you realize that not all changes are good changes. Sometimes, it’s good to recognize that what you’re doing is already correct and to stay with it.

Saurabh: Moving to the next question, how big is the problem of urban sustainability? Urban sustainability challenges have become global challenges.

What role do you think cities or corporations can play in ensuring that buildings from the ground up become green cities?

Ashwin, participating in a Leadership Program on Corporate Sustainability at Stanford University

What are the major challenges and roles for corporates in these green cities?

Ashwin: That’s an interesting question because we’re talking about urban areas and cities. One thing we need to differentiate is that “cities” usually refer to larger urban areas, while “urban areas” can include smaller towns. For example, sustainability in a city like Bangalore differs from Pune or Bhopal. This perspective is important.

From a policy or institutional perspective, when discussing urban sustainability, there’s a lot of government involvement and corporate roles. However, our cities and urban areas have a weak and fragmented institutional architecture.

There are multiple parastatal agencies working under different bosses and departments, pulling their own strings. This creates overlapping responsibilities and challenges.

For example, urban development authorities build infrastructure, while public corporations provide water, electricity, and transportation. In this challenging situation, there are a few areas where corporates can make an impact, especially in building green cities from the ground up.

Of all the carbon emissions in urban areas, around 30-45% comes from the real estate sector—specifically from construction and buildings. It’s not the vehicles or industries, but the buildings that contribute significantly.

The real estate sector has a big role in managing the embodied carbon in construction materials and in designing sustainable buildings.

From my own experience, post-COVID, we revamped our central head office in Bangalore. It spans 60,000 square feet, but the building’s windows didn’t open. Bangalore has a good breeze for eight to nine months, but without operable windows, we had to keep the AC on all the time, which is a design flaw.

We also considered installing solar panels, but the roof wasn’t designed to support them. Such roadblocks highlight the need for better initial design and planning.

The real estate sector and corporates can push each other to ask the right questions and make sustainability a criterion when evaluating spaces to lease. It’s a collective effort from both builders and tenants to ensure sustainable practices are implemented from the start.

Ashwin Kak presenting road safety best practices at an industry summit organised by an Industry Association, during his time at AB InBev in India

Saurabh: Right, right.

Ashwin: These are a few points where I think corporates can play a huge role, other than, of course, actively participating in a lot of civic initiatives. Structurally, this becomes the top area for me.

Saurabh: On that note, to complement what you just said, in the Earth5R app, we have a feature called the personal sustainability survey. Citizens, whether they are working in offices or students, can do a self-survey. This survey contributes to their personal sustainability profile because we feel that individuals do have an impact on the places they live as well as on other citizens.

You know, you’re a corporate citizen or a citizen in your locality. They find out whether their building has a rainwater harvesting system, rooftop solar arrangements, or wastewater recycling. This information comes from millions of data points and is very helpful.

We’re learning some interesting realities about cities, like how many people are unaware of these features. As you rightly said, having this awareness and asking the right questions as a tenant or resident influences the entire system as a whole.

Scientist and author of Cradle to Cradle, Michael Braungart, as the chief guest at the Sustainability 100+ platform conducted by AB InBev and Network 18

Ashwin: You mentioned rainwater harvesting. In Bangalore, during the water crisis, we weren’t getting enough water. In our society, we started asking each other, “Do we have a rainwater harvesting system here?”

Many of us had been living there for years and only realized we didn’t have one when the water stopped. Despite Bangalore being a progressive city with proper regulations, we were caught unprepared.

Saurabh: Yeah.

Ashwin: It’s interesting when you realize this. And you would think that corporates are educated people. This is where sustainability knowledge and proper awareness are very important. With changing global challenges, our understanding should also evolve.

More knowledge and awareness about environmental issues and solutions are crucial. So how do you think the innovative economy can be leveraged to drive sustainability practices better? What is the innovative economy, and how can we leverage it?

Ashwin: When we talk about the innovation economy, I’ll stick to the example of Bangalore because it’s relevant and will help us.

Saurabh: Bangalore is in the news right now. It’s a big global case study. So, yes.

Ashwin: Please go ahead. We’re looking for more information about problems and solutions here. When you ask about the innovation economy, it’s also a startup hub. There are many avenues for collaboration among startups, corporates, and the government.

For example, Bangalore is a lake-based city, not one of those larger cities on a riverbank. It has many man-made lakes from centuries ago that sustain its water requirements. These lakes were intelligently designed with connecting Rajakaluways or water bodies that manage water flow and prevent flooding.

Learning from past innovations, there are many things we can do. For instance, Rajakaluways have become drains today, but they used to be an interconnected system that managed water levels.

Some citizen groups are thinking about creating cycling paths on top of these Rajakaluways since they spread across the city and connect it. This could solve transportation issues without creating new paths.

Banglore is famously known as the lake city.

We’ve also worked with startups on solutions like extracting potable water from air moisture, which has progressed significantly in recent years. Such innovations can address major issues without relying on expensive options like water mafias, which create problems during summer.

Another innovation is hydroponics for growing vegetables and horticultural crops. I’ve connected with people who left corporate jobs to explore hydroponics commercially. This innovation culture in Bangalore provides the right network and supporting infrastructure.

Bangalore could become a hub for urban sustainability innovations. The city gets enough rain to sustain itself, but poor water harvesting practices mean we don’t capitalize on it. It’s not rocket science; proper harvesting is key.

It takes a village to produce a crop – Ashwin with the team that brought the 360 degree farmer connect to life with the Smart Barley program in North India at AB InBev.

Saurabh: That’s very interesting. The solution is within the city itself; you don’t need to go outside and take water from villages. There is no need to take their water.

Ashwin, what role does public policy play in facilitating urban development efforts, and how can companies effectively engage with policymakers?

What are your thoughts on that, especially when it comes to urban governance in general?

Ashwin: I would say the 73rd and 74th amendments, if I remember correctly from the early 1990s, actually enabled the creation of a third level or layer in our urban governance, right? These amendments allowed the creation of urban local bodies and granted them significant power.

However, there is a dispute about how much power these amendments truly grant municipalities. There is a difference between the spirit of the amendments and their implementation. Many of us don’t even remember the mayors of our cities, and some cities haven’t had a mayor for years.

This indicates a challenge in the authority, accountability, and power given to municipalities, mayors, and local bodies. There are many aspects that need to change, but that’s a larger policy discussion. I recently debated this in a public policy course.

There’s a quote, “Everyone wants power devolved or delegated to their level, but no further.” This highlights a challenge in urban governance. I’ll leave the audience with that thought.

Now, for the second part of your question: how do corporates engage and create impact?

Ashwin with the sales team of Fevicol of Western Uttar Pradesh in North India, at the very beginning of his career with Pidilite

Saurabh: Yes.

Ashwin: Corporates can engage in meaningful ways rather than superficial activities. For instance, they can add value to existing initiatives. In Bangalore, there’s a private-to-public initiative involving organizations like WRI, Janagraha, and BPAC, along with the government.

Corporates can drive conversations around these campaigns with their employees. This is a low-hanging fruit. Utilizing public infrastructure, which is often underutilized, is another area where corporates can make a difference.

We discussed innovative solutions earlier. For example, Bangalore has connecting drains that link all the lakes in the city. These could be repurposed into cycling paths, addressing both transportation and infrastructure issues. Of course, safety concerns must be addressed, but it’s an innovative idea.

Corporates should also implement and benchmark their sustainability policies, encouraging employees to follow suit. We’re running a campaign on urban mobility for corporates, focusing on this aspect.

Corporates need to recognize the structural challenges in governance but should not use them as an excuse to do nothing. These are just a few areas where corporates can make a significant impact.

Corporates need to recognize the structural challenges in governance but should not use them as an excuse to do nothing. These are just a few areas where corporates can make a significant impact.

Saurabh: Sure, sure. Ashwin, can you share some success stories or even failure stories from your work in various industries? How can corporates play a big role in sustainability in urban areas?

Ashwin: I’ll start with the failure stories, as I’ve learned the most from them. Spent grain, a byproduct of the brewing process, is often sold at throwaway rates. We started an initiative in southern India, working with communities to use spent grain as cattle fodder to increase milk productivity.

This worked well in Telangana, but not in Sonipat. We realized that milk productivity in Haryana was already high, so spent grain didn’t make a significant difference. This taught us that replicating initiatives without understanding local contexts is ineffective.

In terms of successes, one notable project was installing a drinking water unit on the fringes of Bangalore municipality with AB InBev. This self-sustaining model involved creating infrastructure, training people, and then having the community run it.

It was successful because it didn’t require perpetual corporate involvement, allowing us to focus on other areas.

Another successful initiative was a wide-scale skilling project during my time at Pidilite, in partnership with the government of Gujarat. We worked on skilling rural people in various trades, such as carpentry.

This initiative was successful due to strong government support and a well-structured program.

Saurabh: What kind of skills were you teaching? Were they for rural carpenters or other trades?

Ashwin: So, this was different in many ways because these ITIs had over 20 skills that were delivered through them. Pidlite was a knowledge partner with the government of Gujarat on skilling in general. It also brought its own specialized skills in carpentry, plumbing, and electrical equipment because those were products that Pidlite was selling in many of those industries.

So, Pidlite introduced its own additional skill set in these areas. This wasn’t just a corporate entity trying to generally skill everyone; it was a corporate that had a good understanding of specific skill sets in certain industries. From a commercial practitioner’s perspective, it could bring this expertise to the youth and people trying to upskill themselves.

Pidlite could also employ them, as they were its customers. They started a program called Sati during my time as an area sales manager in the Pune branch. We piloted this program, which was a loyalty program for carpenters and contractors.

No other company had ever done this. In the last 15 years, it has grown to have hundreds of thousands of carpenters and contractors registered. These experiences helped Pidlite gain confidence in forming such partnerships with the state, as the company had its ear to the ground.

They could understand the needs, wants, and desires of that community, leading to a successful partnership.

The government of Gujarat’s skilling department was also very positive. They never approached it as just their problem or solution. It wasn’t just a funding partnership; it was a strong, co-created knowledge partnership, which is why it worked well.

Ashwin, with the India Procurement and Sustainability team at AB InBev, celebrating the win of awards at a Procurement Leadership Forum

Saurabh: So now that we’ve heard about the role of corporates, and we’ve also discussed urban sustainability and the role innovation can play.

How do you foster civic partnerships for impact?

What role do these partnerships play in achieving sustainability goals?

Ashwin: Everything we talked about couldn’t have been possible without an on-ground partner. As corporates, we always had a strong implementation or NGO partner. One satisfying campaign for me was the Save the Beach campaign on Juhu Beach.

This ran for around one and a half years, involving many well-meaning people from Juhu who gathered once a week. It wouldn’t have been possible if run solely by a corporate not even headquartered in Bombay.

We partnered with Earth Day Network and involved the municipality, especially during the launch on World Environment Day 2018, when India was the host country. And we started with a small group of eight or nine partners, but it gained momentum, and by the end, over 100 local civic bodies and citizen groups had joined.

We knew continuous beach cleanups wouldn’t be a permanent solution, but they raised enough civic awareness for people to start asking the right questions. During the cleanups, we empowered and trained people to ask why the beach was getting polluted in the first place and understand the waste’s source.

Another initiative was the urban mobility campaign for corporates in Bangalore, recently restarted. This was a collaborative effort involving organizations from different sectors, including a real estate industry body, the Bangalore Political Action Committee (BPAC), the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) Sustainable Transportation Lab, and the ICT Forum for Sustainable Cities.

The campaign created an extensive questionnaire to evaluate how corporates encourage urban mobility and commuter experience for their employees. The campaign aims to reward the best practices and create an urban mobility toolkit for corporates by the end of the year.

Saurabh: Will there be documentation available for others to access about this toolkit?

Ashwin: Yes, the documentation will be available at the end of the campaign. Right now, the team is reaching out to corporates, learning their best practices, and getting them to fill out self-assessment forms.

Once it’s ready, we would love to publish this information because it’s an interesting and unique experiment in India, similar to those done in European cities like Copenhagen.

Saurabh: Ashwin, can you tell us about your recent immersion in urban governance at the Takshila Institution, especially your work with slums and the manifesto for zero slums in India?

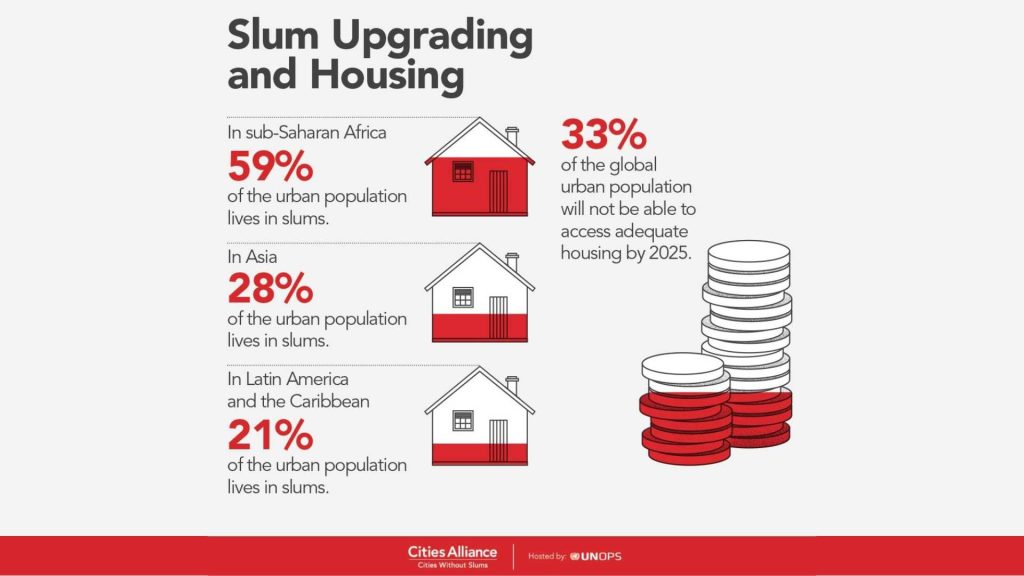

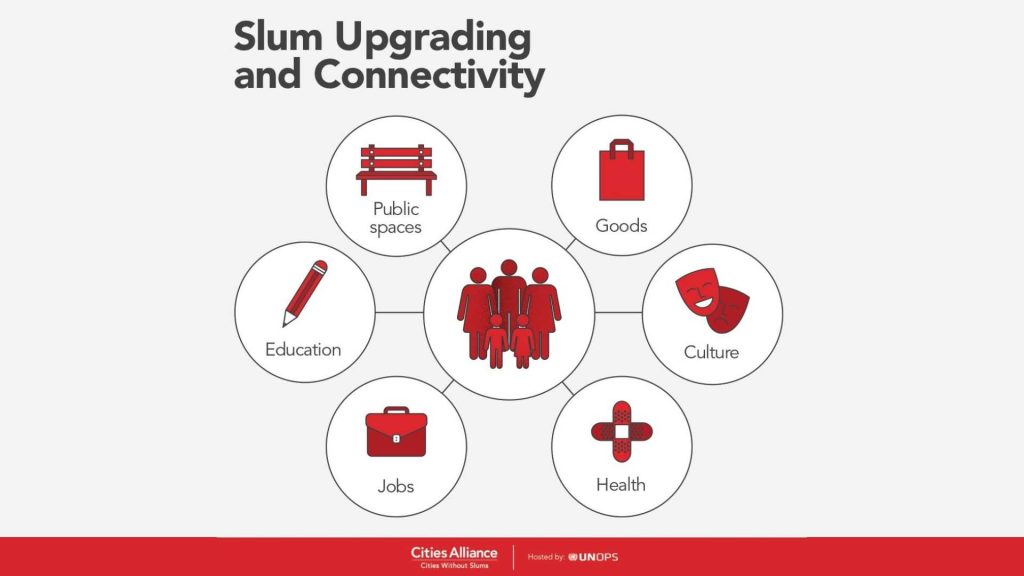

Ashwin: It’s a very ambitious attempt to create a manifesto for zero slums in India. When looking at livability in cities, the slums consistently come up. There’s a lot of literature, research, and action on slum rehabilitation and resettlement, but none of these solve why slums come up in the first place.

Through this research, I aimed to understand the best practices globally and learn from India’s context. There are issues like high population migration, poverty, income inequality, and lack of public services and infrastructure.

Three top solutions in the manifesto include developing regional hubs instead of just smart cities, considering urban employment schemes similar to NREGA, and reforming land management policies, like the floor space index (FSI), to manage urban density better.

Mixed neighborhoods where high-income areas support low-income ones can also help. These solutions have been successful globally and need to be implemented in India.

The reality of slums around the world

Saurabh: Can corporates play a role in this?

Ashwin: Corporates can play a vital role, especially in public service and infrastructure delivery. Industry apprenticeship connectivity for skilling, like Pidlite’s partnership with the government of Gujarat, is crucial.

Corporates can also contribute to housing neighborhoods and urban development. Devashish Dhar’s book, “India’s Blind Spot: Urban Areas and Cities,” discusses how India can benefit from a night economy, similar to cities like Bombay. Utilizing public infrastructure at night can add value without straining resources.

The Team at AB InBev India is driving supply-chain sustainability with its supplier base

Saurabh: That’s interesting, but night economies can bring challenges like noise and light pollution, and biodiversity impact. How do you address these issues?

Ashwin: We don’t need to develop the entire city for a night economy, just specific clusters to maximize public infrastructure utilization. For example, hospitals operate 24/7. Buildings like schools and colleges could be utilized at night. It’s about finding the right balance.

Factors impacting slum upgrading and connectivity

Saurabh:These are really amazing answers. We’re understanding a lot more about urban sustainability and the role policy and corporates can play.

Now, for the benefit of a lot of our audience who are college students, school and college students, or even assist people who are working in the corporate sector but want to switch to the sustainability sector, they want to become CSR professionals, or they want to become sustainability professionals.

So, is there anything you can, I would like to share with them about what areas they should be working on, what skills they need to develop, what they should read, what they should learn about?

Ashwin: Sustainability is dynamic, and professionals need to embrace this fluidity. Young professionals often feel shaken by the lack of consistency, but it’s essential to see this as an opportunity for efficient and better solutions.

Hands-on experience, learning, and failing are crucial. The gap between research and practice must be reduced. Sustainability professionals need to understand the business, technology, and policy aspects of sustainability. They should be generalists in navigating these verticals.

Hands-on experience, learning, and failing are crucial for the improvement of Cities. The gap between research and practice must be reduced. Sustainability professionals need to understand the business, technology, and policy aspects of sustainability.

Saurabh: Do you think HR or marketing professionals are more suited for sustainability roles?

Ashwin: I have a take on this, which might disappoint a lot of my colleagues. But see, when you started talking about HR, right, we need to understand. There are a few companies, and this has been happening with a lot of Indian companies ever since the CSR law came in 2014. It was voluntary at first, then slowly it started being mandatory.

So, a lot of the companies that were pioneers didn’t really face a problem because they, in a way, had teams that were already doing sustainability. They had to restructure and rejig and put a team together. Others, who were late to the bus, started looking at making their HR teams into, for example, their CSR teams.

I would say that’s a very risky slope to be on, right? Because there aren’t very easily replicable or transferable skills. Just because you’re thinking CSR is something where you need to be empathetic and understand the community, and hence the HR will connect with it really well.

Those are not really very easy things to navigate because the HR works within the organization setup while the CSR has a lot of dynamics of the external world which they have never been exposed to. So that’s…the HR piece is troubling to me.

What I can still understand is when legal and compliance professionals start moving into ESG, and these are different terminologies I’m using particularly because ESG is a lot of risk mitigation, compliance reporting where a compliance professional fits in really well.

Sustainability again, if you look at how sustainability really works, there, I won’t constrain it to where people can come from, because I have seen people coming from different domains and fitting in.

But they need to, as I was saying, you know, start learning the other technical aspects, the policy aspect, so I would say it is less about which function leads to which functions more seamlessly. It’s more about how that individual is involved, but this HR thing is very risky.

Indian companies should stop seamlessly integrating HR teams into CSR teams. That’s my take.

Saurabh: Ashwin, thank you so much. This was really an amazing talk, and we have learned a lot from your experience and from your policy background.

We would like to talk to you again sometime in another podcast on a different topic, but thank you so much for sharing all your knowledge and your experience from the corporate world and your background in policy. Are there any parting words you have for our audience?

Ashwin: Thank you, Saurabh. This is a great series of podcasts and ideas that you have around this. This is my discussion of what I have understood in terms of your vision for what this podcast should turn out to be.

My best wishes. I think there’ll be a lot more master classes and experts will be coming in and sharing their views, and I’m looking forward to seeing this grow.

Ashwin, with the Vietnam and Southeast Asia Supply-Chain team, while heading the Procurement & Sustainability function at AB InBev India and South-East Asia.

– Reported by Ashi Parelkar

Given link of the podcast : Sustainable Futures Podcast 1: Cities of Tomorrow

In envisioning the cities of tomorrow, sustainability and smart technology must stand at the core of urban transformation. These cities will prioritize green infrastructure, renewable energy, and efficient resource management, fostering environments where innovation meets ecological responsibility. By integrating advanced technologies like IoT and AI, cities can optimize services, reduce waste, and enhance quality of life for their inhabitants. The cities of the future will not only be resilient against climate change but also adaptable to the evolving needs of their communities. Collaboration between governments, industries, and citizens will ensure these cities thrive as models of inclusivity and sustainability. Ultimately, the cities we build today will shape the legacy of tomorrow, driving the global shift toward smarter, greener living spaces.